Hi everyone!

Here's a longer piece I've been working on about Ray Bradbury. He's my favorite author, so I wanted to take some time to look deeper at his work and his perspective. Please note that it's essentially an essay. I'm a nerd. Deal with it, but enjoy!

When one considers the genre of science fiction, the name Ray Bradbury is one of the first people who the brain associates with the genre. Theoretically, Bradbury wrote science fiction. His anthologies of short stories from the future include people living on Mars in automated homes and interacting with aliens. However, Bradbury’s stories always take a turn for the worst: the people die off because their homes have gone haywire or the aliens they are interacting with end up taking the humans prisoner. Hypothetical endings like these tend to make a person quake in his or her boots. Bradbury’s literature almost inspires fear of the future, a place where one’s home becomes the enemy or the new, exciting life forms become dangerous tyrants or even predators. This is how Bradbury’s renown came to be. His horrific style, although in the science fiction genre, proves his prowess in unsettling a reader. Ray Bradbury, although exalted as one of the greatest science fiction writers, should actually be remembered as a horror writer. His mastery of language allows him to write across genres and combine elements of his nucleomituphobia-filled world, terrifying psychological situations and reactions to nuclear war, both by natural and synthetic beings.

Bradbury weaves a vivid future, with appliances that are completely automatic and where interplanetary travel is completely feasible. However, Bradbury’s take on Earth’s future is not entirely his own creation. Isaac Asimov, another famous science fiction author, depicted a completely beautiful 2014, in which humans and robots have found a harmony with nature in a column he wrote for The New York Times. Asimov based his estimations off of his time at the 1964 World’s Fair, an exhibition of the newest technologies, inventions and estimations of what future technology will be like. He saw 2014 and the years after as a time of prosperity, where humans live underground in order to keep the earth above green and austere, whether it be with crops or forests. However, Asimov’s positive future comes with a large challenge: the neglecting of nuclear weapons. Asimov states outright in his piece in The New York Times in 1964 that, “If a thermonuclear war takes place, the future will not be worth discussing.” The world had seen the extreme damage that took place in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Asimov only wanted to depict a future that was not post-apocalyptic rubble, a la "Hunger Games." This quite positive expectation of the future was not shared by Bradbury, however. Bradbury agrees with Asimov when it comes to the new, load-bearing appliances and automated homes, but not in a thermonuclear fashion. In many of Bradbury’s short stories, nuclear war is either imminent or already happened. His view of the future is not negative per se, rather his view of the human race. Bradbury does not believe an idyllic future is feasible, by any means, at least when it comes to his short stories. His foreseeing of the human tendency to collapse into war shows his readers the doubt he places in humanity and their creations.

Bradbury took his doubt of humanity’s creation especially seriously in his short story, “The Veldt.” Focusing on a nursery that creates sense-illuminating worlds, this story proves to be psychologically terrifying based on the nursery’s commitment to create a ‘real’ experience. In the small family Bradbury creates, the children are the most connected to the nursery, to the extent that one could call the nursery a necessity for them instead of an extraneous pleasure. It is this connection that causes the mayhem in the family. The parents, although the story is told from their point of view, become the antagonists, for they want to shut down the nursery and move to the countryside temporarily after the children choose to ‘imagine’ Africa for weeks on end. The mother, Lydia, reacts the worst to the mental rut the children are in, and she initiates an inspection of the nursery with her reluctant husband, George. They experience the nursery in its most perfect form: their senses tell them they are in Africa, although they have not even left their home. This is distressing to Lydia, but George ridicules her, convinced that the nursery is just doing its job. However, when the lions the nursery projects begin to stalk them, they both sprint out of the room in fear. Lydia is rattled. “‘Oh George!’ She looked beyond him, at the nursery door. ‘Those lions can’t get out of there, can they?’” (274). This is merely the beginning of the psychological trauma Bradbury is looking to exact within his readers. A combination of paranoia branching from getting too comfortable with technology and lack of control over one’s children is the starting point for the mental terror this story inflicts, according to Jason Boyd. Boyd goes as far as saying “our mastery of nature…is a detriment.” In this context, he is correct. Technology has progressed so far that it brainwashed two children into a constant need for it. Even their parents are confused by the alternate reality the nursery provides. George remembers the fear he felt from the close encounter with the nursery’s lions, thinking “That sun. He could feel it on his neck, still, like a hot paw. And the lions. And the smell of blood” (274). Truly what started as a story about parents worrying about their children became a terrifying account of technology doing its job too well. This theme of technology going haywire because of its commitment to do its best can be found throughout Bradbury’s fiction, as a contributor to the psychologically-distressing idea of the future.

Technology doing its job too well and thermonuclear war juxtapose each other nicely when it comes to Bradbury’s science fiction. These two motifs, complete comfort and utter destruction, enhance Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains.” This short story, set in the single house left standing after a nuclear bomb strikes a town, explores how technology would conceivably live eternally without humans. According to Bradbury, the robots would still serve the memory of the long-extinct humans, in a never-ending charade of normalcy. He describes the automated house as “an altar with ten thousand attendants, big, small, serving, attending, in choirs. But the gods had gone away, and the ritual of the religion continued senselessly, uselessly” (237). This is what is what leaves a reader aghast when (or if) he or she ponders human extinction: humanity’s finiteness. If the human race were to disappear, then the only remaining evidence of humans, the robots, would act as if nothing happened and continue along in their content existence, preparing breakfasts for mouths that cannot talk anymore, cleaning hallways that are never tread in, and drawing baths for no one. If this image is not outright terrifying, then it is at least uncomfortable or strange to consider. Even the strange, ever-serving home enters a state of robotic confusion in which fears creep into its circuitry. The house, after losing its tenants, becomes scared of anything that moves.

“It had shut up its windows and drawn shades in an old-maidenly preoccupation with self-protection which bordered on a mechanical paranoia. It quivered at each sound, the house did” (237).

For the reader, this is a new level of psychological fear to be added to the previous ones delivered by Bradbury. Even the robots of the future, in their eternal quest to serve an extinct human race, become scared of whatever else remains. In an analysis of this story from Elon University, Bradbury is described as a genre-jumping author, with “There Will Come Soft Rains” cited as evidence. The Elon University analysis puts Bradbury into three categories: fantasy, due to his creation of a house that serves no one; horror, because of because of his post-apocalyptic setting; and science fiction, Bradbury’s ‘home genre’. This categorization is proof that Bradbury cannot merely be considered a science fiction author only; his fiction is too broad to be placed under one category. He weaves a horrific, futuristic style that focuses on the cons of a highly-technological age, warning humans of the past and present of the dangers of technology becoming too prevalent in daily life.

Bradbury belabors the same lesson constantly in his short stories: do not become obsessed with technology. His future humans do not understand this lesson, and function as teachers by example, showing the reader the danger(s) that way. For example, “The Veldt” has two technology-obsessed children in it, named Peter and Wendy. Throughout the whole of the story, these children are on a quest save their precious nursery from being shut off by their parents. When Peter and Wendy trick their parents and lock them in the nursery, the story becomes blood-freezingly chilling. The psychiatrist that their parents had been meeting with shows up at the house, and finds the children, but no parents.

“The children looked up and smiled. ‘Oh, they’ll be here directly.’” (286). The psychiatrist suddenly becomes aware of what has happened when he sees the lions eating a fresh kill in the distance. The children, living up to their creepy obsession, act as if everything is normal.

“‘A cup of tea?’ asked Wendy in the silence” (286). Clearly, the danger of losing technology moved two children to killing their two parents. The deaths of the parents are not described, so one could assume that the room itself also fought on the children’s side to prevent its robotic form of death, being shut off. Humans of the future are willing to kill over the simplest technology according to Bradbury. The inhumanity of the robots has spread to the humans, making the world a dangerous place to live in.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” is another prime example of the struggle between humanity and inhumanity. However, this time there is not outright murder in the short story. All the humans are dead already in the town of Allendale, California, after a nuclear bomb dropped. Mere shadows of humans are the only things left, besides the rubble and a single home. These are Bradbury’s tool to show the reader that the inhuman has prevailed. Only “ five spots of paint -- the man, the woman, the children, the ball -- remained” out of a whole town that was once there (236).

Despite the lack of humans, the house cleans and prepares meals without any response. When the house does recognize one voice, it is the voice of the family dog, now emaciated and sick. Consequently, the house lets the dog in. This humane treatment of an animal lasts for only the morning. When the house begins baking, it fills with delicious smells, to which the dog reacts poorly: “It ran wildly in circles, biting at its tail, spun in a frenzy and died. It lay in the parlor for an hour” (237). The house lets the dog lay like that for a full hour before finally sending out the small robotic maid-rats to tear it apart, piece-by-piece. Obviously an inhumane way to dispose of a body, this truly shows the strength of the inhuman spirit. Even when the parts collected reach the incinerator, it can be described as glowing happily, as if the house was waiting to kill the dog for the entire time the dog was inside. The Elon University analysis calls this the synthetic being winning over all of nature. However, according to Elon University, the home loses to nature in the end. It dies in a fire caused by a tree falling through one of the pristine windows. This can be seen as the human prevailing from the afterlife. The final inhuman invention that remained standing has been destroyed by the natural. This postmortem success, however, is too late to be called winning a battle against the oppressive robots. Bradbury’s haranguing on the same moral is meant to show the reader that taking each decision slowly is best for matters of technology. Rushing into a decision leads to something bad, usually death or mass death in Bradbury’s stories.

This carelessness in decisions takes center stage in “The Last Night of the World.”Bradbury experiments in this short story with the idea of the mass extinction which removes humans from the Earth. In the collective unconscious, the event of human extinction becomes a lawless fight for any version of survival, whether it be under the ground (think "City of Ember"), under the sea or in the air. Bradbury contradicts this collective thought with “The Last Night of the World.” Despite their imminent doom, his characters find it comforting and even calming in knowing the end draws near. “‘Sometimes it frightens me, sometimes I’m not frightened at all but at peace’” (363). The preceding quote comes from the father of a family of four. He, along with many other adults, experiences a biblical dream of warning, but unlike the holy figures, but no action is taken. In fact, both him and his wife treat the day as if it were any other day. They eat dinner with the family, put the children to bed, wash the dishes, and retire quietly. Despite this charade of normalcy, the parents tend to try and justify their conspicuous sense of calm.

At work, the husband asked around, and found that many of his co-workers experienced the same dream. When asked, one of his coworkers “‘...didn’t seem surprised [but rather] relaxed, in fact’” (364). Of course, this lack of a reaction differs from the reader’s expectation. Bradbury uses this as a testament to the insensitivity of human action. In this particular story, humanity reached the brink of technological use and fell off the proverbial cliff -- making “The Last Night of the World” a testament of Bradbury’s correctness in making up technological prophecies. Truly, this short story applies to today’s society as well as the future Bradbury weaves. One can almost hear Bradbury speaking when he writes the husband saying, “‘In a way, that’s something to be proud of - like always’” (365). ‘Like always’ is the overreaching, omniscient statement that conveys Bradbury’s disappointment with the technologically advances that, in his mind, function as the metaphorical asteroid which ends human life. Whether or not Bradbury finds joy or shame in the second mass extinction is up to a psychologist. All the reader can determine about Bradbury shows Bradbury as a stern, disapproving god who wields lightning bolts as weapons.

Ray Bradbury should not be classified as some sort of misanthrope who waits for the end of humanity with glee. Rather, his prophetic predictions of technological-based doomsday(s) should be seen as the 1960's version of transcendentalism. He calls for a return to simpler life or a least a slowing of technological advancements. Events like the Cold War, the dropping of atomic bombs and the Space Race affected Bradbury’s view on new, exciting innovations. He saw the danger in leaving a simpler way of living behind and warned against the technological terrors. His short stories, especially “There Will Come Soft Rains,” “The Veldt” and “The Last Night of the World” explore the psychological and literal dangers branching from the machines that began piquing interest and enthusiastic support of the population within the era he wrote. Although Bradbury’s prediction may have not come true yet, his preaching against the obsession with technology remains completely relevant in society today. The ‘Prophet Bradbury’ may still predict the future accurately with his short stories, only if the collective technological obsession escalates so far that human contact becomes limited. The preservation of human contact and connection with nature is Bradbury’s ultimate goal for humanity, and if followed, will prove Bradbury’s prophecies of a death by nuclear weapons or the ever-increasing forms of technology.

Going to the cinema alone is good for your mental health, says science

Going to the cinema alone is good for your mental health, says science

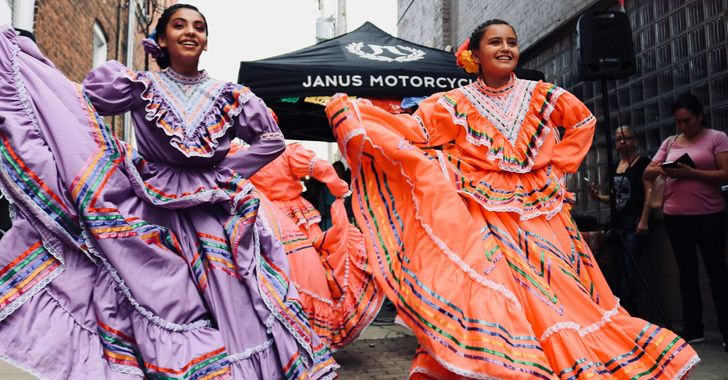

women in street dancing

Photo by

women in street dancing

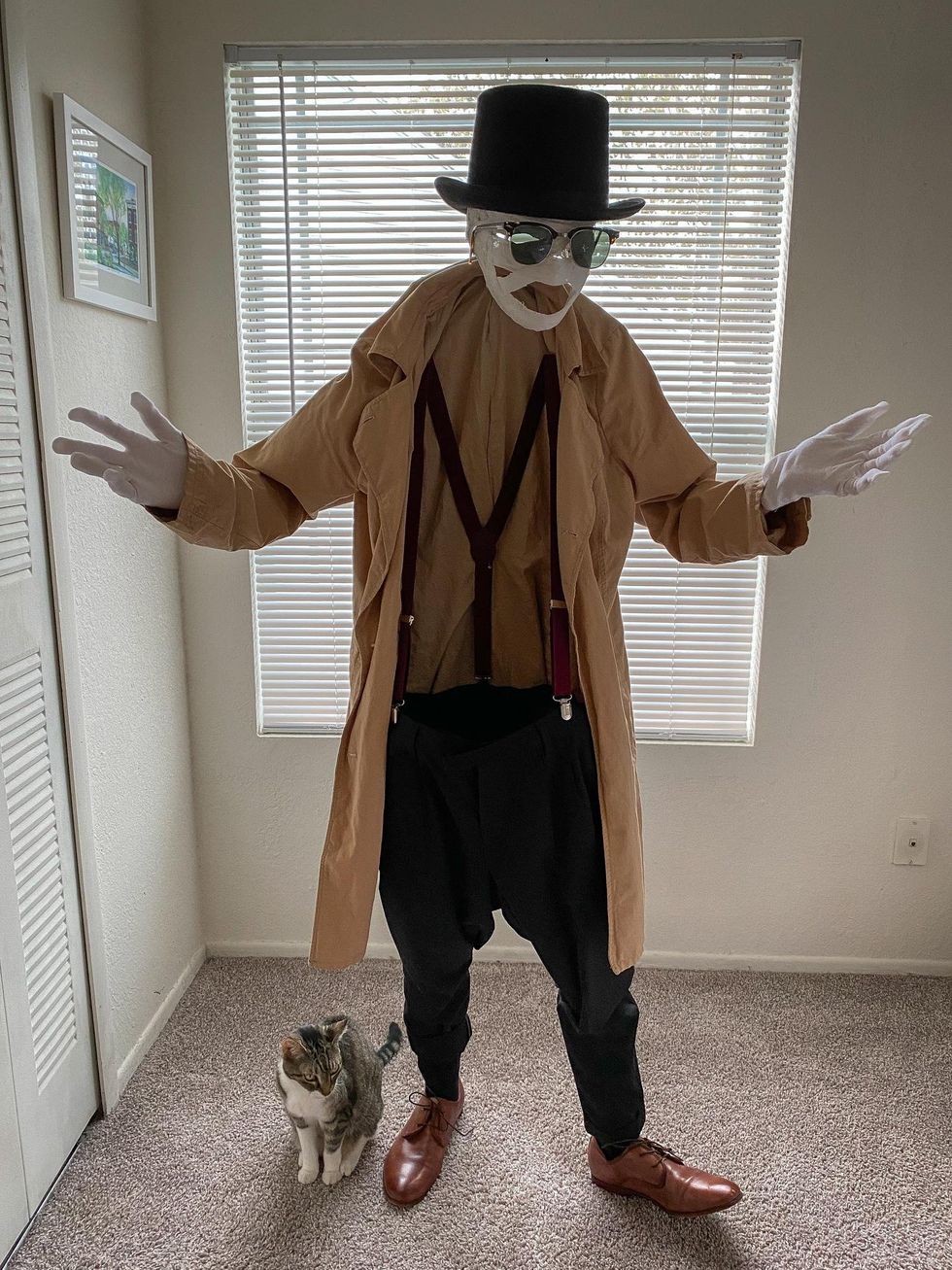

Photo by  man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by

man and woman standing in front of louver door

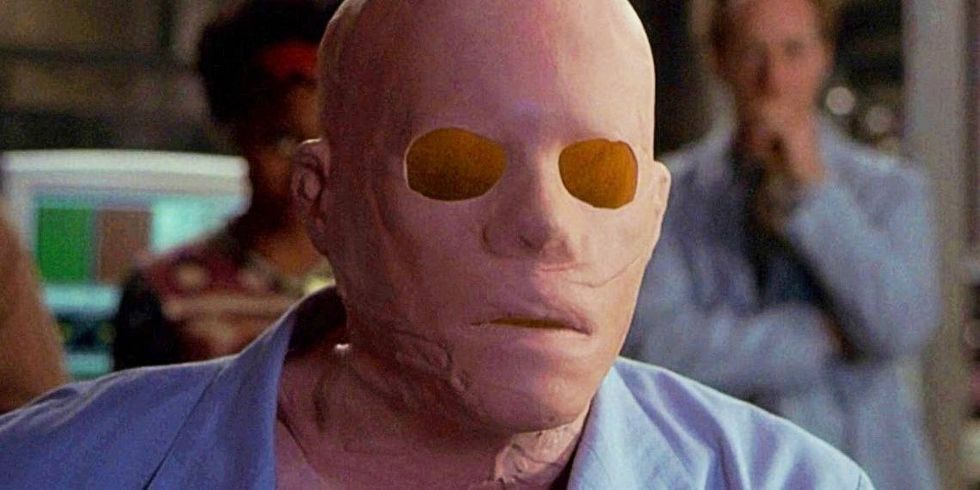

Photo by  man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by

man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by  red and white coca cola signage

Photo by

red and white coca cola signage

Photo by  man holding luggage photo

Photo by

man holding luggage photo

Photo by  topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by

topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by  trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by

trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by  Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by

Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by  man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by

man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by  difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by

difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

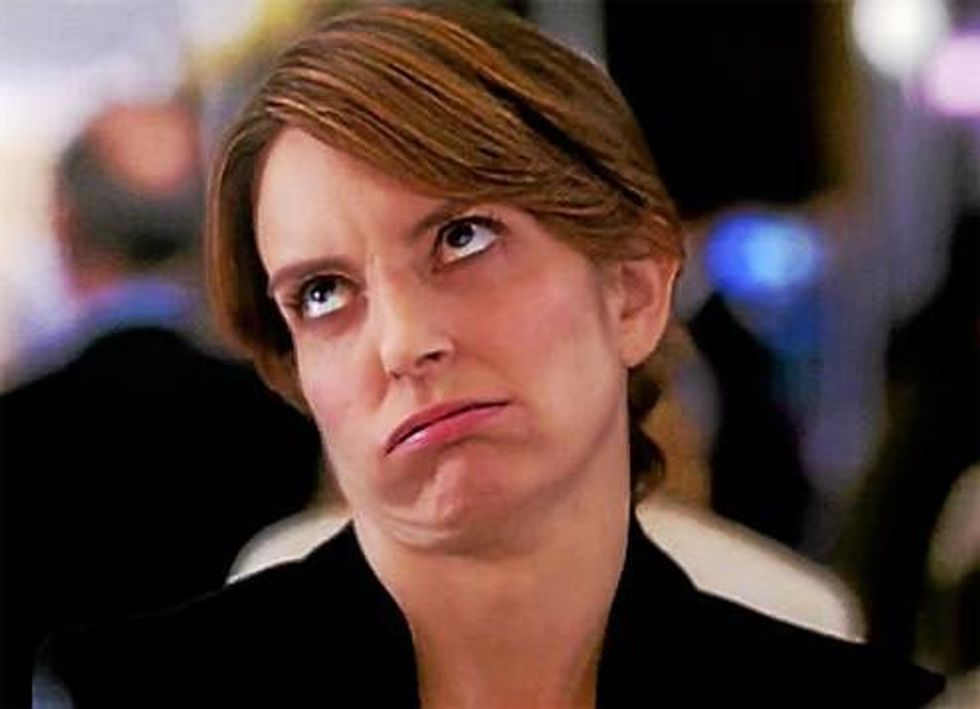

Photo by  photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by

photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by  closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by

closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by  a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by

a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by  two men

two men  running man on bridge

Photo by

running man on bridge

Photo by  orange white and black bag

Photo by

orange white and black bag

Photo by  girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by

girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by  assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by

assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by  three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer