The close of the twentieth century in the Arab world marks a distinct transition to authoritarian rule. United by pan-Arab ideals, Egypt, Syria, and Iraq all introduced a new style of personalized government employing the selective use of repression. In Syria, the Ba’ath Party’s 1971 coup d’etat ignited a surge of power by the Alawite minorities. The new Ba’athist president of Syria, Hafiz al-Asad, wasted no time in building an authoritarian, single-party state. By the time he transferred power to his son, Bashar al-Asad, in 2000, surveillance and repression had crushed nearly all opposition. Zakaria Tamer, who was driven out of the country due to his outspoken opposition to the authoritarian state, illustrates this repression in a series of micro-level short stories. His tenth collection, titled Breaking Knees, focuses heavily on sexual repression in everyday life. Sexuality in Tamer’s Breaking Knees functions as a double entendre: although the stories can be interpreted primarily as the repression of female sexuality by males, male sexuality also serves as a metaphor for the repressive authoritarian rule in Syria.

According to novelist Halim Barakat’s typology of Arab literature, a novel of exposure “exposes the weaknesses of society and its institutions without exhibiting real commitment to the restructuring of the existing order” (216). As a collection of short stories in which each story has different characters, Breaking Knees does just that. Tamer explores various themes of injustice and oppression in the Syrian state -- namely sexual, religious, and political repression. But as a novel of exposure, Tamer’s stories do little more than illustrate the perpetual repression evident in an authoritarian state.

Breaking Knees protests a repressive society as much as it protests a repressive authoritarian regime. The novel’s translator, Ibrahim Muhawi, writes in his introduction: “The general theme of Breaking Knees, as is much of Tamer’s work, is repression: of the individual by the institutions of state and religion and of individuals by each other, particularly women by men” (ix). Sexual repression by institutions assumes the form of marriage and religious customs. Sexual repression by individuals includes gossip, nosiness, talking about the opposite sex, adultery, and role reversal, but it is most evident in scenes of attempted sexual assault.

The eighth and ninth stories in this collection demonstrate men’s use of fear and force in rape attempts. In the eighth story, a seemingly innocent girl is watching a movie when a man enters the cinema and starts fondling her. “She was about to protest,” the narrator says, “but he leaned over and whispered in her ear that she’d better keep quiet if she didn’t want to cause a scandal, one that hurt women more than it hurt men” (11). The man uses the threat of a damaged reputation to frighten the girl into submission. At that point, she freezes and submits herself to violation. The plot thickens, however, when the girl proves herself experienced with sexual encounters such as this one: “she reached for him and started feeling him with nervous, greedy, experienced fingers” (11). The girl’s lack of naivete seems to be what drives the man away. He immediately snatches back his hand and rushes from the theater. The man frightened the girl into submission in hopes that he would stain her innocence, but when she proves herself experienced and not at all naive, he loses interest.

The ninth story also begins with a presumably innocent woman, this time in an orchard. A man appears before her, threatening, “Careful! If you scream, I’ll kill you” (12). In this story, the man uses fear of force to subordinate the woman. The fear in the woman’s eyes excites him: “The woman was filled with terror, and her face turned pale. The man was pleased to see her fear, and wanted to enjoy more of it” (12). When he tells the woman that he will rape her, she sighs “with relief, ignoring the knife close to her” (12). To the woman, the threat of rape is much less of a concern than the threat of death, and though the man preys on her fear, she does not fear rape at all. In reply, she asks the man a series of explicit questions about the rape he has planned. Her questions reveal that she is not at all inexperienced in sexual encounters:

"Are you going to rape me here, in this orchard? [...] Or will you take me to a house with a bed? Are you going to rape me standing up, leaning against a tree, or lying on the grass? Do you want me to take off all my clothes, or some of them, or are you going to rip them with your hands and teeth? And when you rape me, do you want me to keep quiet or moan with pain? Do you want me to cry and beg, or laugh and get excited? Are you going to rape me once, or a number of times? Will you alone rape me, or are you going to share me with your friends?" (13).

Upon realizing that the woman is not afraid of sexual assault nor inexperienced in this area, the man returns his knife to its sheath and flees the scene. Again, the draw for the man seems to be the woman’s fear and innocence, but he loses interest when the woman is no longer afraid and no longer presumed innocent.

By placing these stories side by side in the collection, Tamer allows the reader to recognize common themes among stories of sexual aggression. First, the men both employ fear as a subordinating tactic, and they enjoy provoking fear in the women. The man in the first story uses fear of a damaged reputation to make the woman submit to violation; in the second, the man uses fear of violence. The men both enjoy the pleasure they receive from instilling fear in a woman, and they take advantage of its success in making the women submit. Both times, the women freeze in compliance. Also, both stories indicate a double standard for male and female sexuality. While the men are clearly experienced and know exactly how to approach a sexual situation, they expect the women to be inexperienced, naive, innocent virgins. This desire for an inexperienced woman is not confined to the context of sexual assault. Throughout the novel, men repeatedly express their wishes for a “naive and innocent woman” to marry (7). In the two stories discussing sexual assault, both men are surprised by the women’s comfort in sexual situations -- so much so that they no longer desire to assault the women, almost as if the excitement was in the women’s virginity. The women’s perceived fear and lack of experience excites the men, but as soon as they learn that the women are not afraid or inexperienced, they lose interest.

The men in these stories use fear and force as subordinating tactics, and the same could be said of the authoritarian government in Syria. Hisham Sharabi, author of Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society, describes the nuclear family as the model of neopatriarchal society and identifies the father figure as the “central agent of repression” (41). Sharabi also introduces authority, domination, and dependency as the driving forces of modern Arab society. He says that these three “both reflect and are reflected in the structure of social relations” (41). In other words, neopatriarchal society triggers the cycle of authority, domination, and dependency to the father figure as much as the father figure builds a society upon these three values. If the family unit is the model of society, and if its head -- the father -- regularly employs repression, then one can expect a government in neopatriarchal society to employ repression as well. Such was the case in Syria under the Asads.

Just as the men in Tamer’s stories used fear and force to subordinate women, the authoritarian state used fear and force to subordinate its citizens. During the rule of Hafiz al-Asad from 1971 to 2000, surveillance drastically increased. He decimated the public activities of all dissenters, forcing the Muslim Brotherhood underground. Hafiz al-Asad also violently crushed the Hama Rebellion in the 1980s, setting the precedent that the authoritarian state would not hesitate to use force in order to maintain dominance over its citizens. Much like the men who used fear to force themselves upon women, the authoritarian government in Syria used fear to ensure that the government remained supreme. Hafiz al-Asad’s violent reaction to the uprising in Hama also demonstrated a double standard: Syria’s authoritarian government would not tolerate violence against it, but the government did not hesitate to employ violence against its citizens, almost too eagerly. Much like men expecting women to be inexperienced in sexual encounters despite their own extensive experience, the authoritarian government also held itself to a different standard than the standard by which it judged its citizens.

According to Halim Barakat, the characters in a novel of exposure experience troubles on an individual level, but they do not credit their troubles to the issues in society as a whole (Barakat 216). In Tamer’s Breaking Knees, this inability to acknowledge widespread problems in society enables individuals to submit to repression without recognizing that they are repressed. This lack of knowledge is consistent with Hisham Sharabi’s assertion that domination in neopatriarchal society reinforces the status quo and “makes people blindly opposed to social change” (Sharabi 42). In the stories of sexual assault attempts in Breaking Knees, women see their predicament as inevitable, so they find submission the easiest choice. Likewise, citizens of the Syrian authoritarian regime see their repression as inevitable and therefore insurmountable.

Barakat identifies that a novel of exposure does not commit to a solution for the societal problems it outlines. Perhaps this is because its characters can see no opportunity for change. Repression in Syrian society is like air: so evident that it can no longer be detected. Individuals are repressed by each other and the state, and to them, there seems no alternate way of life than to be censored and repressed. A life of fear is a grave reality for citizens of Arab authoritarian regimes. Censorship and repression have become evident not only in the government, but also in society as a whole.Works Analyzed

Barakat, Halim. "Creative Expression: Society and Literary Orientations." The Arab World:Society, Culture, and State, University of California Press, 1993, pp. 206-38.

Sharabi, Hisham. Neopatriarchy. Oxford University Press, 1992.

Tamer, Zakaria. Breaking Knees. Trans. Ibrahim Muhawi. Reading, Berkshire, UK: 2008.

Going to the cinema alone is good for your mental health, says science

Going to the cinema alone is good for your mental health, says science

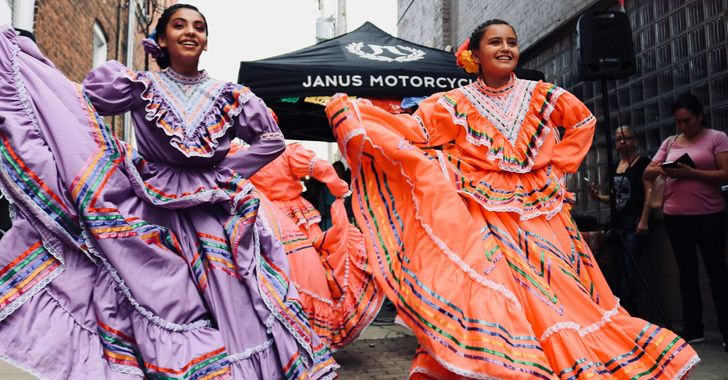

women in street dancing

Photo by

women in street dancing

Photo by  man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by

man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by  man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by

man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by  red and white coca cola signage

Photo by

red and white coca cola signage

Photo by  man holding luggage photo

Photo by

man holding luggage photo

Photo by  topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by

topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by  trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by

trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by  Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by

Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by  man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by

man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by  difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by

difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by  photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by

photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by  closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by

closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by  a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by

a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by  two men

two men  running man on bridge

Photo by

running man on bridge

Photo by  orange white and black bag

Photo by

orange white and black bag

Photo by  girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by

girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by  assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by

assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by  three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer