“So,what are you?” What a way to start a conversation.

It is natural for human beings to be curious. Seeing something different triggers a need for more information. This is where my problem starts.

I can belt out every word to "The Star-Spangled Banner," albeit rather off-key. I learned about the pilgrims and the Indians and the Mayflower and the 13 colonies, and that in 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue. I read every American Girl book and even had a magazine subscription. I mourn on Sept. 11. I delivered an Oscar-winning performance as a sheep in my first grade play. I watched PBS Kids. I volunteered at a call bank during President Obama’s reelection campaign. I juked at all of my homecoming dances, was class board president, went to football games, basketball games, prom, and I would eat Chicago-style cheese pizza over anything.

I grew up here. This is my home. Can’t you be content with, “I’m from Illinois”?

When you ask me what I am, it tells me that you see me as something different. Someone unlike you. That you are unable look past my appearance enough to see me as solely American.

Every single person in this country stems from a different cultural root, myself included. We live in the same country yet define one other by ethnicities much like the way the Hutus only saw Tutsis instead of being united as Rwandans. While the comparison to genocide is a definite hyperbole, it cannot be denied that it has become impossible to stop focusing on our differences rather than our similarities, and yet we wonder why there is so much hate in this world.

It’s such a harmless question but it exhibits the weakness in our mindset: you do not look like me, therefore you are something different. I will always fail to understand how looking different began to mean being different.

The stranger thing is that this question isn’t just being asked by the girl in my math class but also by my entire system. I cannot even count the number of times that I have had to tick “Asian” on a form. I understand the need to maintain a record of ethnicities for immigrants, but once someone decides to become a naturalized citizen or is born in the United States, can we end the story at simply being Americans? Evidently, demographics have become important enough to have separate segments on nearly every application, ranging from scholarships, to federal aid, to even college, but it begs the question... Why does it matter?

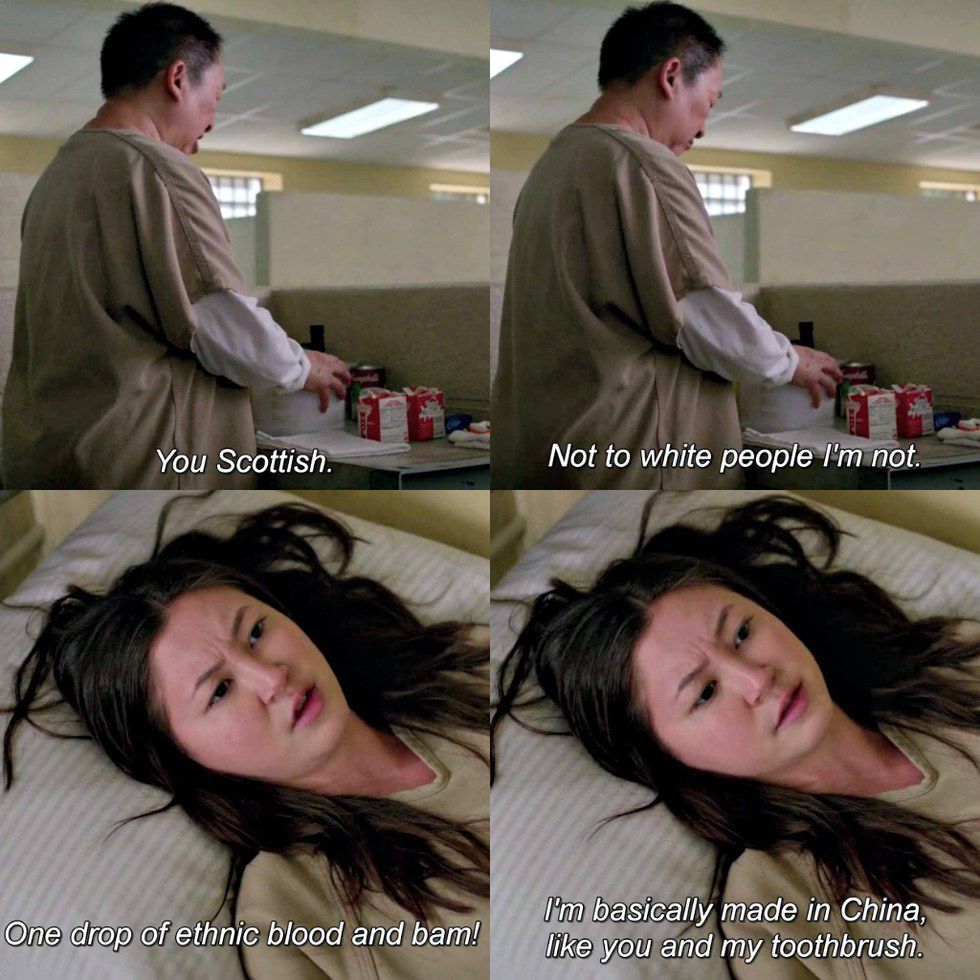

I am proud of my cultural background. It is a part of my life and has an influence on who I am. While I am well learned in the important aspects of my heritage, I can’t pretend that I understand it as well as someone who is actually a native in that country. A Filipino American doesn’t know exactly what it is like to be a Filipino living in the Philippines. This leaves us with a partial knowledge of our backgrounds, but a strong understanding of American culture as we have been raised here. Despite this, when someone asks us what we are, we are forced to refer back to our semi-culture.

Half-Kenyan Barack Obama. Cuban-American Senator Ted Cruz. African Americans. Asian Americans. Irish Americans. Hispanics. Latinos.

Allow my culture to remain a part of who I am, but don’t let it be the distinguishing factor that prevents you from seeing me as an American. This is not about denying one’s heritage, but rather altering how we define American citizens.