When considering one of America’s most prominent historical issues, it would be impossible to ignore the vices that racism has brought to our society. However, United States citizens are prone to not being able to acknowledge the prevalence of American racism, contributing to its overdue longevity. The belief that racial prejudice no longer exists in America has been the main reason why racism has become institutionalized or established in practice of custom.

American writer, lawyer, actor, and commentator on political and economic issues, Ben Stein, is one of those who are ignorant of the fact that racism does still exist. In an interview on Fox News on October 22nd, 2017, Stein was quoted to have said:

“These guys are a bunch of sulking big babies. They don’t know what they’re talking about. There’s no institutional racism in America at all anymore. If they want to do their free speech thing, God bless them. Let them do their free speech thing. But let's ignore them from then on. Let's just ignore them like they're bad babies and we don’t want to hear them crying off in the corner. Yes, there’s racism in every human being’s heart. There’s no institutional racism in America anymore. It’s gone.” (Stein 2017)

In rebuttal to NFL players peacefully protesting against prejudice, Stein called for football viewers to ignore the progressive acts of various players across the league, and dispelled the “myth” that institutional racism exists. Despite my own personal opinion on the amount of stupidity it takes for a person of decent knowledge to proclaim something of this magnitude, multiple instances in history can make my point clear enough. Through the history of African-Americans, Middle Eastern-Americans, Native-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Latin-Americans, tangible evidence of the institutionality of racism in favor of the Anglo-Saxon race is clearly confirmable.

Institutional racism in the United States first began in 1619 in Jamestown, Virginia, when the Dutch nations of Europe brought African slaves into the New World to cultivate virgin soil, harvest lucrative tobacco plantations, and build up an economic system that set the foundation for Colonial America. African slaves were bought, sold, and traded into America in order to have a system of labor that was cheap and easily manageable for their white “masters”. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, which helped solidify the need for slaves in the South due to the growing demand for cotton products in Northern and Southern America.

An estimated 6 to 7 million slaves were transported to the New World from Africa in the 18th century alone, leaving the motherland devoid of their strongest men and most fertile women. This dynamic caused America to grow prosperous and wealthy at the expense of African natives, and Africa became a struggling land filled with broken homes and damaged families.

In 1865, slavery was formally abolished in America, granting approximately 3.9 million slaves emancipation. Unfortunately, the practice of marginalizing and disenfranchising African-American men has been a continued practice to this very day.

Instead of the traditional form of slavery that was practiced in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, America is now the home of mass incarceration, the substantial increase in the number of incarcerated people in the United States' prisons over the past forty years. Through racial profiling and stereotyping, African-American men have become targets for police and law enforcement’s disposal, and the judicial system has never been more supportive of this unfair use of jurisprudence in decades.

From the plantations to the prisons, African-American men are being detained, arrested, and convicted in extraordinary numbers. According to Avaaz, a global web movement that aims to bring people-powered politics to decision-making everywhere, “there are more African-Americans in prison or jail, on parole or on probation today than there were slaves in 1850” (Avaaz 2017).

The system of mass incarceration has been coined the “New Jim Crow” by sociologists due to the increased amounts of African-Americans in prisons and their separation from general society. Once imprisoned, the black man is denied his right to vote, prohibited free contact to friends and family, and forced to live and operate on the terms of his prison guards and warden, a lifestyle that is closely parallel to that of the slave man. By replacing overt slavery with covert slavery, “the man” has made it legal for African-Americans and other minorities to be oppressed at an even greater number than they were before.

On March 2nd, 2017, Ashley Crossman published an article entitled, “Definition of Social Oppression”, where she explained and analyzed how groups hold power over others in society by maintaining control over over social institutions, and society’s law, rules, and norms. In this article, she claimed, “Social oppression is a concept that describes a relationship between categories of people in which one benefits from the systematic abuse, exploitation, and injustice directed toward the other” (Crossman 2017), perfectly describing the nature of slavery in old America, and the nature of institutional racism of new America. The benefactors of mass incarceration primarily include white men, granting them more opportunities in the social, economic, and political worlds.

A clear-cut example of the oppressive system of mass incarceration is evident from none other than an active Louisiana Sheriff himself, Steve Prator. In an open speech to the community of Louisiana, Prator went on record saying, “In addition to the bad [prisoners]... they’re releasing some good ones that we use every day to wash cars, to change oil in the cars, to cook in the kitchen, to do all that where we save money. Well, they’re going to let them out ― the ones that we use in work release programs.” (Prator 2017) This is proving that the exploitation of prisoners is used for the benefit of those who make a living by oppressing the prisoners.

Incarceration is no longer used to rehabilitate or reconstruct criminals, but to demoralize and capitalize off of vulnerable prisoners. Prator described in his speech how “good prisoners” were better kept in jail because they were the best workers, more humble, and most likely less galvanized to disobey the orders of the wardens, guards, and other prison staff. According to Wiley Reading, a writer on social malpractices in America, “African-Americans and Hispanics comprised 59% of all prisoners in 2008, even though African-Americans and Hispanics make up approximately [25%] of the US population” (Wiley 2014).

This statistic goes to show how African-Americans and minorities are generally targeted, preyed upon, and thrown into a system of oppression for the benefit of the white man. Because minorities groups typically have access to inexperienced lawyers, mediocre public defenders, and worthless legal representatives, it is easy for them to fall victim of being trapped in this system of oppression.

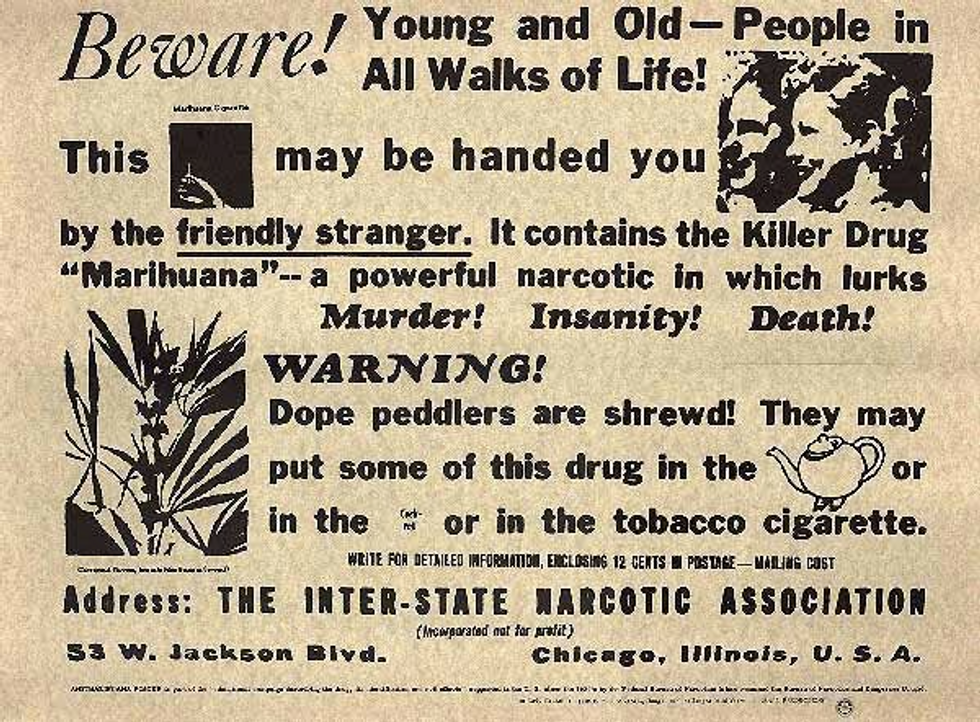

The War on Drugs (1969-1974) set the precedent of racial profiling and drug arrests that is still apparent today. Former President Richard Nixon, a confirmed racist, made it his priority to lower the amounts of drug crimes in America by cracking down on drug users, distributors, and cultivators. What really happened is an instantaneous boom in the amount of African-Americans that were arrested for petty drug crimes.

Prior to 1971, prisons were comprised of 95% white men. After the war on drugs was commenced, those same prisons were comprised of 95% African-American men. This dynamic change was based on a crackdown of inner cities, poor urban communities, and communities that were predominantly inhabited by minority groups. Due to the gradually increasing rate of African-American arrests, there are currently more African-American men that cannot vote in America today than there were in 1870 when the 15th amendment was passed, granting them the right to vote.

It goes without saying that the War on Drugs was just a way to marginalize both citizens of minority ethnicities and African-Americans, but the fact that this practice was blindly followed by law officials is completely sickening.

The list of ways America has practiced new ways of enslaving African-Americans and institutionalizing racism can go on forever, but not enough emphasis has been placed on the ways we can end systematic oppression once and for all. One of the best ways of implementing a new social relationship between whites and African-Americans is instilling a pedagogy in society, where whites are willing to listen to the plights of blacks and work to create a fair nation for them.

Blacks are also willing to work with whites in creating a new future for the youth of America, a future that lacks the elements of hate, prejudice, stereotyping, and ignorances of the past. One of the best proponents of creating a new system of oppressed-oppressor relationships is Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator and philosopher who was the leading advocate of critical pedagogy. In his book, "Pedagogy of the Oppressed" (1968), Freire proposes the following theorem:

“A revolutionary leadership must accordingly practice co-intentional education. [The oppressor] and [the oppressed] (leadership and people), co-intent on reality, are both Subjects, not only in the task of unveiling that reality, and thereby coming to know it critically, but in the task of re-creating that knowledge. As they attain this knowledge of reality through common reflection of action, they discover themselves as its permanent re-creators. In this way, the presence of the oppressed in the struggle for their liberation will be what it should be: no pseudo-participation, but committed involvement.” (Freire 1968)

In this quote, Freire believes that the only way for a society to progress and build upon its previously failing system in practice is by both the oppressor and the oppressed working together to recreate a new system of successful interaction, communication, and cohabitation. Both whites and African-Americans must ban together to dispel the generation curse of hatred and animosity, and bring to life a system of education, acceptance, and respectful liberation.