Meet your new favorite word: "Zaftig."

Zaftig refers to full-figured, plump, round, overweight, thick, or fat women but with none of the negative baggage other size-related words entail. It comes from the Yiddish zaftik, meaning juicy or succulent.

Why do we need zaftig in our vocabulary? To find out, I interviewed my good friend Celeste Kamiya, a sophomore theater major at Eugene Lang College. Celeste is the one who introduced me to the term, so I picked her brains to find out how she came to champion zaftig and why we should all follow her lead.

Me and Celeste (right), 2014

She started her story in high school:

“I decided to start acting like I thought I was a knockout, drop-dead hottie. (Initially) it was to impress a guy, actually… I started to see myself and my figure in a much more positive light than I ever had before. And then I began to notice things my friends, peers, and loved ones would say that were really hurtful, ideas that I had always internalized before, micro-aggressions or just straight-up insulting comments that demeaned overweight people.”

For Celeste, the “fake it ‘til you make it” attitude worked–sort of. Feeling better in her own body was great, but it didn’t change the fact that American culture is vehemently anti-fatness.

A Cult of Thinness

Celeste's embrace of zaftig runs counter to our thinness obsessed culture. The history of America's obsession with monitoring bodies – particularly those of women, people of color, queer people, and the disabled – deserves its own full set of encyclopedias, but for my readers' sake I will try to outline just the modern context of fatphobia.

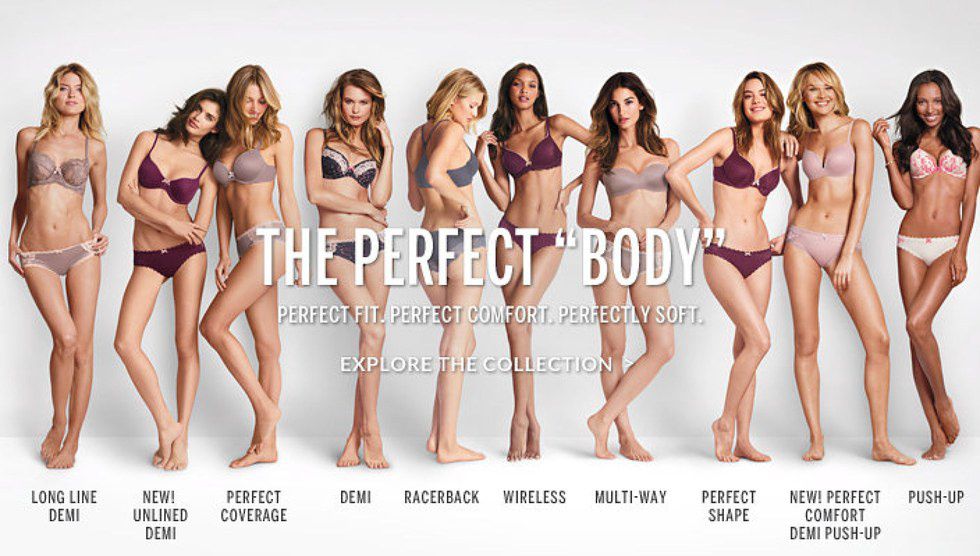

I hope it is not news to anyone that America's expectations of women's bodies are ridiculous. (If it is, go watch Miss Representation on Netflix and get back to me). Models, actresses, news anchors, and nearly all visible role models for girls are thin, emaciated, or at least not fat. They are also likely role models because of that physical trait. The average model is between 5 foot 9 inches and 6 foot tall, weighing 110 to 130 pounds. By contrast, the average American woman is 5 feet 4 inches at 166 pounds according to the U.S. Census. These stats directly translate into young women's lives: stores like Abercrombie and Fitch, Lululemon, and Brandy Mellville (all of which have cult followings of girls/young women) carry extremely limited sizes or, in Brandy’s case, one size only. These beacons of “cool” have sent a very clear message–you must be this thin to ride. The CEO’s have blatantly said so. Growing up in a whirlwind of Barbies and Victoria's Secret models deeply distorts many women's self-perception.

As athleticism becomes more and more competitive and praised, boys and men are increasingly affected by unrealistic body expectations as well. Many noted that Bryce Harper's appearance and description of his physical preparation in Sports Illustrated's body issue clearly demonstrated the extreme and potentially fatal lengths men will go to in order to obtain the ideal athletic body type.

It is worth noting that men get the counter-image of "Dad Bods," which absolutely does not exist for women, despite the fact that biologically-female women are the ones who carry children and therefore have a physical reason for gaining weight with parenthood. Oh, the hypocrisy.

In fact, it is not just men who suffer due to our workout mania. People of all genders are suffering from muscle dysmorphia, a psychological disorder that causes an obsession with gaining muscle definition no matter one's physical reality, at increasing rates.

Many sociologists have remarked that the gym has become the new church. We go regularly to atone for our sins (eating "bad" food, eating too much, being lazy) and it is seen as immoral and condemning not to partake. It is an individual communion between oneself and the spirit of fitness. Proper attire is required. Instead of "Jesus Loves You" signs, there is "fitspo" (fit inspiration) proclaiming "Sweat is just your fat crying."

The consequences of fatphobia are astounding. According to sources, 20 million women and 10 million men suffer from a significant eating disorder at some time in their life. Eating disorders are mental illnesses that, similar to clinical depression, can be triggered by outside factors such as cultural pressure to be thin and personal trauma. Do not underestimate the severity of these illnesses: As the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders states, "the mortality rate associated with anorexia nervosa is 12 times higher than the death rate associated with all causes of death for females 15-24 years old."

Fatphobia works quickly too: 40-60 percent of elementary school girls (ages 6-12) are concerned about their weight or about becoming too fat. 50 percent of teenage girls and 30 percent of teenage boys use unhealthy weight control behaviors such as skipping meals, fasting, smoking cigarettes, vomiting, and taking laxatives to control their weight.

Clearly the deep moral judgement we place on fatness is extraordinarily influential, as Celeste recalled:

“My peers would talk during lunch about how fat they were getting, how they needed to lose weight — and I would look at their thin, conventionally attractive bodies and my dimpled, overweight frame and I would think, ‘Do my friends think I need to lose weight? If they’re worried about gaining weight because they think it’ll make them look bad, how bad must I look in their eyes?’”

Fatphobia is Insidious

How many times have I said something fatphobic about myself? How many times did I say it in front of Celeste? I have known far too many young women with severe eating disorders and as a feminist I think about body standards a lot. I really should know better...and yet I still said it.

Celeste neatly summarized the “woke”-but-still-fat-shaming phenomenon:

“If you’re a good, kind, normal, non-Trump-supporting person, you’d never insult somebody’s race, religion, class, gender, sexual orientation, or ability in public where people can hear you and call you a …bigot (or) asshole. But plenty of good, kind, normal, non-Trump-supporting people laugh at fat jokes and talk about how desperately they want to lose weight because they think being fat means being ugly.”

The social stigma of fatness is so engrained in our culture that it becomes a knee-jerk reaction, along with self deprecation. I have always thought Celeste is stunning. I can't think of a single time I genuinely judged or disliked her body, so why was I so quick to hate mine?

Even smart, otherwise non-judgmental people can fall back on habits of fat-shaming, particularly because the fat-positive movement is relatively new and small.

A New Frontier of Activism

Zaftig is from the vocabulary of the burgeoning fat-positive movement. You may have heard it described as “body-positivity,” but Celeste pointed out that fat-positivity more accurately calls out the problem.

“The idea of thinking of fatness in any kind of positive light is so deeply radical…as opposed to ‘body positive,’ which is kind of a universal given, even if people don’t truly believe in it.”

Similarly, I say “feminism” not “humanism,” and “black lives matter” not “all lives matter.” All of it is true, but the idea is to focus on marginalized groups for once.

The fashion industry has gotten a lot of flack for smoothing out fat-positivity into meaningless “body-positivity.” First of all, “plus size” models generally range from an American size 10-14. I sometimes wear a size 10 and I don’t think anyone would classify me as plus-sized or zaftig. I have heard insider tales of models padding themselves to reach plus-sizes, which creates images of plus-sized women with thin legs, tiny waists, no rolls, no arm fat, no chubby cheeks, etc.

This is a photo of a model who qualifies as plus-sized.

Even the very limited industry of fashion that supposedly represents and caters to zaftig women shows deeply troubling habits of fat-shaming.

Lately, Aerie has been praised for the "aerie real" campaign. This is a screenshot from their homepage:

It is undoubtedly a great step to stop obsessively photoshopping models and include a little more body diversity, but let's not pretend these pictures are celebrating fat women. This is why body-positivity is easier than fat-positivity. It's just a start to accept that conventionally attractive, light-skinned, thin women have dimples in some places.

Celeste advocates for the real-deal: fat-positivity. She regularly challenges harmful language, draws attention to employment discrimination, and runs a killer Instagram showcasing her fabulous zaftig self.

The yummy sexiness of "zaftig" is a much needed contrast to the viciousness of "fat." Celeste described how this language plays out in her life on a daily basis:

"The other day at the store where I work, a coworker and friend of mine commented that one of the mannequins looked 'so fat in that outfit.' I said, trying as always to be gentle, not to accuse anyone of fatphobia, 'She does look fat. It makes her look awesome. Ain’t nothing wrong with looking fat.' (She) immediately backpedalled, saying, 'I just meant the clothes she’s wearing aren’t very flattering.' I pressed harder, and she danced around my words. The conversation ended with her saying, 'I think being chubby is super cute on a lot of people, but it just would look terrible on me.' Eventually I just smiled and let it go. This kind of interaction happens to me on average about three times a day, every day."

Of course, language is never just language; fatphobia seeps into our employment, economy, and laws. Recent studies (described in Time Magazine) show that "the U.S. has seen a 66 percent increase in weight bias over the past 10 years." It is now well documented that overweight people, particularly women, are less likely to be hired and are more likely to be paid less. While "morbidly obese" people are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act, there is no general protection based on weight or physical appearance. Increasing cases of discrimination against zaftig people and fat-positive activism are finally bringing this issue to the forefront.

Zaftig is Intersectional AF

Fat-positive activism has a chance to create really dramatic change in a wide variety of demographics. Celeste wisely noted that while fatphobia is harmful, it's not quite on the same level as other social justice issues such as police brutality and campus sexual assault.

It's also not trivial. Not only does fat-positive activism address eating disorders, it also connects to larger issues of discrimination in health care, poverty, racism, and (most obviously) sexism.

Broadened understanding of fat-positivity could actually save lives: eating disorders have significant mortality rates and our national obsession with obesity leads to under and mis diagnosis of serious health problems in fat people. Patients have long complained that doctors are much more likely to diagnose overweight individuals with illnesses related to their weight rather than explore all possible diagnoses. Just think of all the time, money, and quality of life we could gain by adopting a more fat-positive outlook.

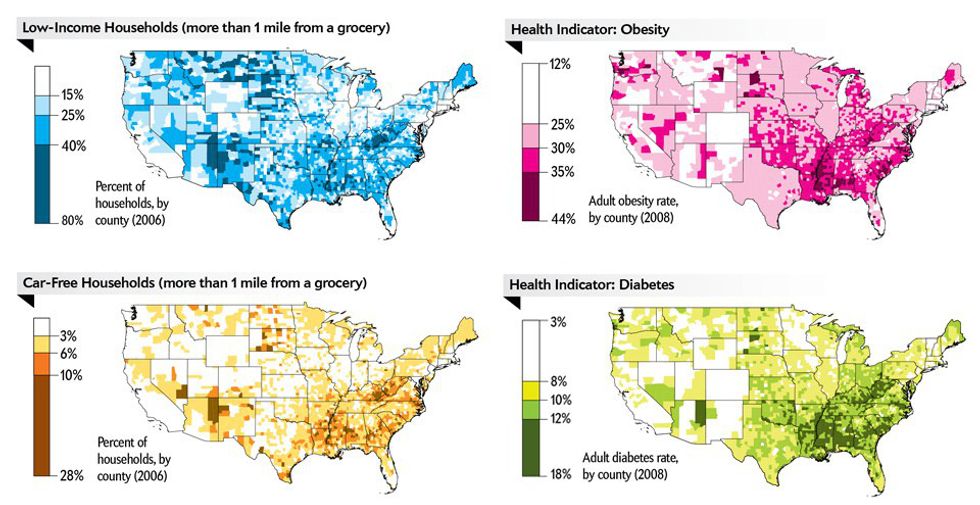

Fatphobia is also inextricably connected to racism. While size does not always (or even often) correlate to health, we also cannot deny the rise of weight/diet related diabetes. The panic over diabetes allows us to treat fatness itself as a disease, and we blame "sufferers" for giving it to themselves. But let's take a closer look at diabetes, poverty, race, and access to food:

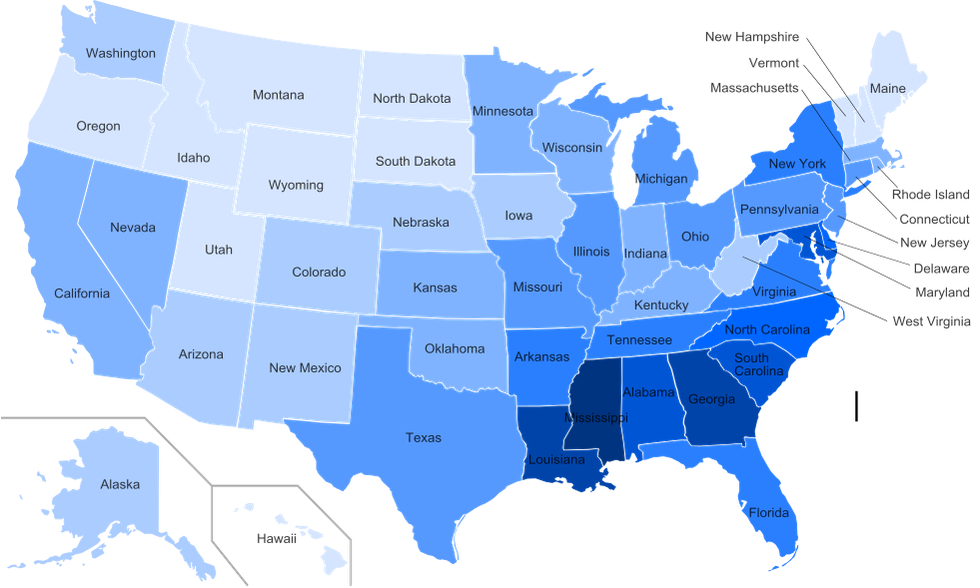

It is no coincidence that the now well-known phenomenon of "food deserts" largely coincides with the poorest southern states, which also have the largest black populations:

Percentages by United States Census, 2010

There is a long, ugly history of attributing unhealthy lifestyle to the innate culture of minority populations. The Chinese were long thought to simply prefer the crowded, unplumbed chinatowns because they themselves were rat-like. Black women have long been associated with rich foods – sugar in particular (*cough cough* plantations). Mexicans are assumed to be fat because their food is supposedly greasy. I could go on. There is nothing biologically or culturally engrained in minorities that makes them diabetic. Racism and immigrant status contributes to ongoing poverty, which determines the quality of food people can access.

However, the shorthand is brown = poor = fat = bad.

Using loving, non-judgmental language like zaftig creates space to acknowledge these histories and current realities.

Self(ie) Love

“You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting 'Vanity,' thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.” – John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Celeste takes selfies on the street, in her room, and in dressing rooms (my personal fave–it's like a never-ending fashion show of zaftig style). Her Insta, @queenofzaftig, is a plethora of positive messages. She is shifting the politics of who gets to take selfies, who gets to be proud of their appearance, who is cool-beautiful-sexy:

"I think selfie culture is an incredibly powerful force for good in the world. Everyone who says selfie culture promotes arrogance or self-indulgence is missing the point; self-love and confidence is a radical act, especially for those whose bodies do not conform to societal beauty standards."

The hope is to flip the script on centuries of objectification. A selfie puts a woman in control of her own body. A selfie of a zaftig woman is the opposite of every skinny, oiled-up, tall, blonde, surgically altered Victoria's Secret campaign: bodily control and self-love for the women we have degraded for the better half of a century.

Zaftig women like Celeste who dare to love themselves are actually chipping away at invisible, massive power structures that stretch far beyond kale salads and Barbies. Do you see it now?