*Note: For this article I will be quoting the Penguin Classics version of "The Prose Edda" by Snorri Sturluson, translated by Jesse L. Byock.*

I know an ash,

it is called Yggdrasil,

a high, holy tree,

splashed and coated with white clay.

From it come the dews

that fall in the valleys.

It will always stand

green over Urd's well.

-- The Sibyl's Prophecy, 19

If any of you have seen the first "Thor" movie, then you may recall a scene in which Yggdrasil is loosely explained. They fit it well into the Marvel universe, making it work with scientific theory and the traditional myths. For Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is at the literal core. It and how it interacts with the world(s) defines the structure of the universe. Here I will begin to explain its vastness and purpose within Norse mythology. I say "begin" because the totality of its being is not complete until the end times and when the rest of the mythology is explained.

Realms/Worlds

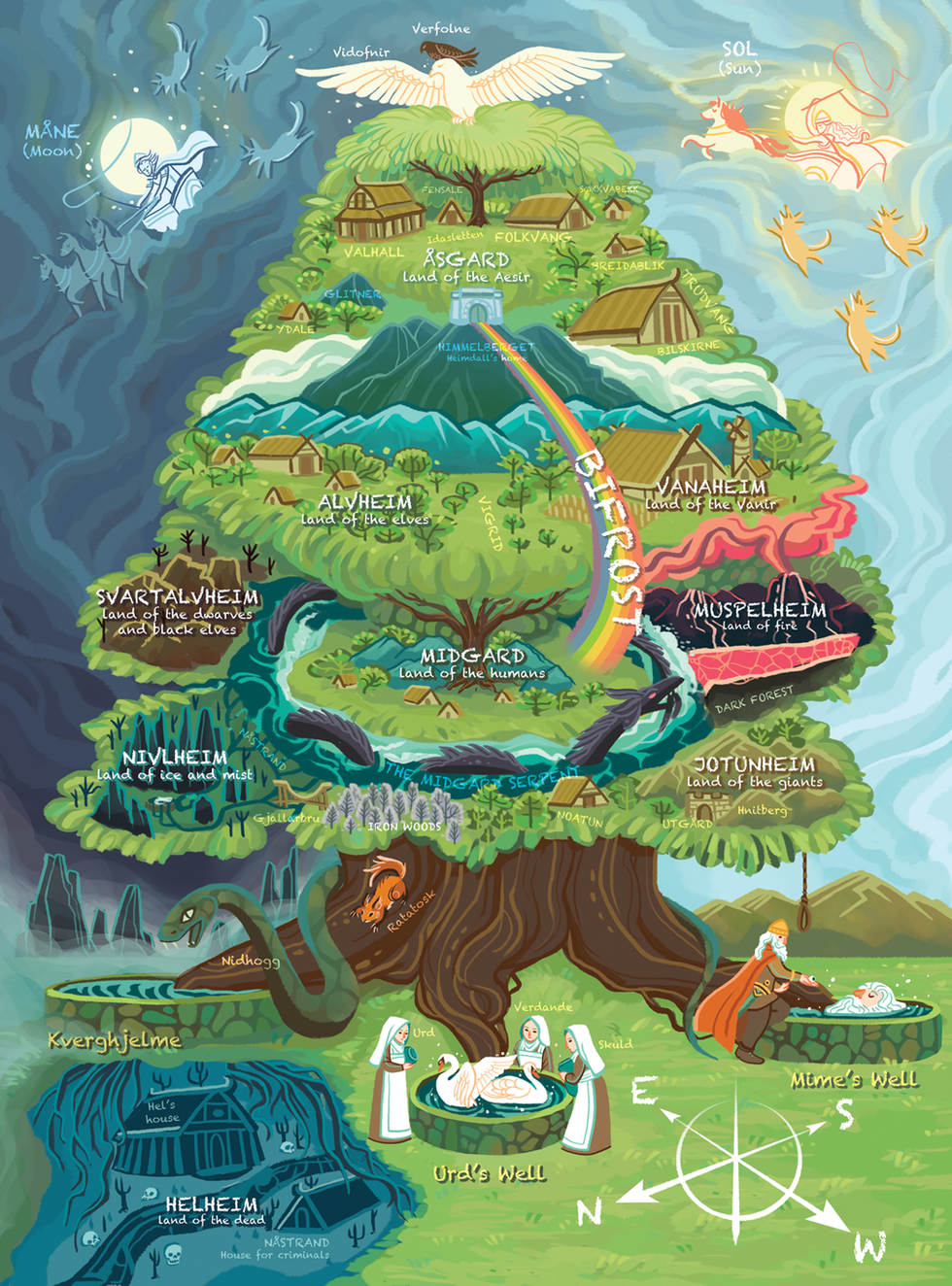

Yggdrasil, pronounced Igg (as in Iggy Azalea) -dras (as in grass with a D) -ill (as insick), is an ash tree. It is "the largest and the best of all trees. Its branches spread themselves over all the world" (p. 24). Yggdrasil is the world tree, that which holds the nine worlds together. And yes, nine worlds, not just your typical three of heaven, earth, and hell. I will go into more detail about each of these realms in another article, but here's a brief explanation and layout:

I will also list the realms since the creator of this picture uses different spellings than I do:

Asgard, land of the Aesir

Vanaheim, land of the Vanir

Midgard, land of Men

Alfheim, land of Elves

Svartalfheim, land of Dark Elves (and Dwarves, in this version)

Niflheim, land of ice and mist

Jotunheim, land of the Giants

Muspelheim, land of fire

Helheim, land of the dead

This is one of the better drawings of Yggdrasil that I've seen. It has a lot of detail in it and I will likely be using it in future articles. However, it is not the only iteration. Here, the nine realms consist of those I just listed. Other versions include Nidavellir, the realm of the Dwarves, as a world and have Helheim or just Hel as part of Niflheim. I have seen both versions equally as much, so it can be hard to say which is right, especially when texts don't offer clarification.

Roots and Wells

Yggdrasil has three roots, where "one is among the Aesir. A second is among the frost giants. ... The third reaches down to Niflheim ... but Nidhogg gnaws at this root" (p. 24). Each root is nourished by a well, represented in the drawing in the foreground. These wells are mentioned throughout the mythos and are central to certain stories, not to mention they help keep the world tree alive. The root that extends to Niflheim has the well Hvergelmir (or Kverghjelme, as the illustrator of the picture spells it) under it, the root to the frost giants has Mimir's well, and the root among the Aesir has Urd's well.

Hvergelmir isn't mentioned too much, but it is noted that many rivers come from its waters. However, Urd's and Mimir's wells are highly functional and sacred within the mythos. Mimir's well is the well of knowledge. This well will be talked about in greater detail when I cover Odin. Urd's well is the well of destiny. Here "a handsome hall stands under the ash beside the well. Out of this hall come three maidens, who are called Urd (Fate), Verdandi (Becoming), and Skuld (Obligation). These maidens shape men's lives. We call them the norns" (p. 26).These Norns care for the root they are near by pouring the water from Urd's well onto it "mixed with the mud that lies beside the well, over the ash so that its branches will not wither or decay" (p. 27).

Travel

As big as this tree is, you may be wondering if anyone travels between the world, and if so, how? The gods use a bridge called Bifrost, "it has three colors and great strength, and it is made with more skill and knowledge than other constructions" (p. 21). This is the Norse Mythology explanation for rainbows. If ever anyone says rainbows are girly, just remind them the Nordic god of war Odin rides over them on his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir. The bridge also protects Asgard because "the red you see in the rainbow is the burning fire. The frost giants and the mountain giants would scale heaven if Bifrost could be traveled by all who wanted to do so" (pp. 25-26).

Inhabitants

There are, as well, some creatures that inhabit the tree. A few of them are represented in the drawing above, but not all. I might as well start with my favorite, Ratatosk. He is a squirrel who "runs up and down the ash" and "tells slanderous gossip, provoking the eagle and Nidhogg" (p. 27). That eagle "sits in the branches of the ash, and it has knowledge of many things" (p. 26). Upon that eagle (no, it doesn't have a name) sits the hawk Vedrfolnir between its eyes. Nidhogg is a great serpent dragon that bites at the roots of Yggdrasil in Niflheim with the snakes Goin, Moin, Grabak, Grafvollud, Ofnir, and Svafnir, all within the well Hvergelmir. Not only is Yggdrasil being eaten from below, but "four stags called Dain, Dvalin, Duneyr and Durathror move about in the branches of the ash, devouring the tree's foliage" (p. 27).

Thoughts

As complex as the cosmological figure of Yggdrasil is, the ideas behind it are those that are in many pagan faiths. A world that is continually growing and dying, living with us as we live on it. It sounds quite hippy-dippy, but there is a soothing calm that is associated with this cycle of the world. The idea that the most solid thing in our lives -- the Earth, or Yggdrasil, or the World as you know it -- reacts and changes just as much as we do is, I believe, an integral realization for a human. As I cover other topics in the mythology, you will begin to see how interconnected Yggdrasil is to everything. From Odin's origin, to the renewal at the end times, the great ash tree serves as a central object throughout. It is the spine of the cosmos, the route of gossip, the ever-eaten and ever-growing. It is home.

Keep growing, my friends.