On January 21, nearly 7,000 people participated in the Women’s March For Arkansas at the Arkansas State Capitol in Little Rock.

The demonstration was intended to serve as a sister march to the Women’s March On Washington, which was the first major Women’s March protest planned as a direct response to the presidential election and inauguration of Donald Trump. On January 21st, Women’s March protests occurred in multiple locations around the world, with global participation at an estimated 4.8 million.

These protests were intended to be a response to misogyny, racism, ableism, and xenophobia espoused by both Trump himself and the Trump campaign, as well as an acknowledgment of the already existing structural oppression of women that allowed for the election of Trump to the White House. Donald Trump is currently the only U.S. president to have ever admitted to committing sexual assault on record, as well as the only U.S. president to have ever been formally accused of raping a minor. His other acts of misogyny include a long history of publicly humiliating and degrading women. In addition, the marches are also intended to be a response to the Trump administration’s jeopardization of the rights of women of color, immigrant and undocumented women, transgender women, gay and same-gender loving women, and gender nonconforming individuals, as well as any woman affected by the new administration’s anti-immigration and Islamophobic rhetoric.

The Women’s March in Little Rock proceeded two blocks from the corner of Pulaski St. to the Arkansas State Capitol where a rally took place on the steps of the Capitol building. The rally featured a number of speakers ranging from Arkansas political representatives to members of the Little Rock public school system. Crystal C. Mercer, activist, artist, and sole proprietor of the Columbus Creative Arts + Activism and Merchant served as the emcee. The lineup included Ana Claudia Aguayo, Development Officer of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and a community activist for the rights of immigrants and the undocumented, as well as Sophia Said, the Programs Director for the Interfaith Center of Arkansas and a distinguished community organizer, among several other speakers. The Vice Mayor of Little Rock, Kathy Webb, drew the speaker portion to a close with a brief speech.

Following this, organizers led the rally into chanting a variation of the presidential oath to “commit to be an active participant in the future of our country.” as stated on the Program page.

The oath followed, “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute my role as an American and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

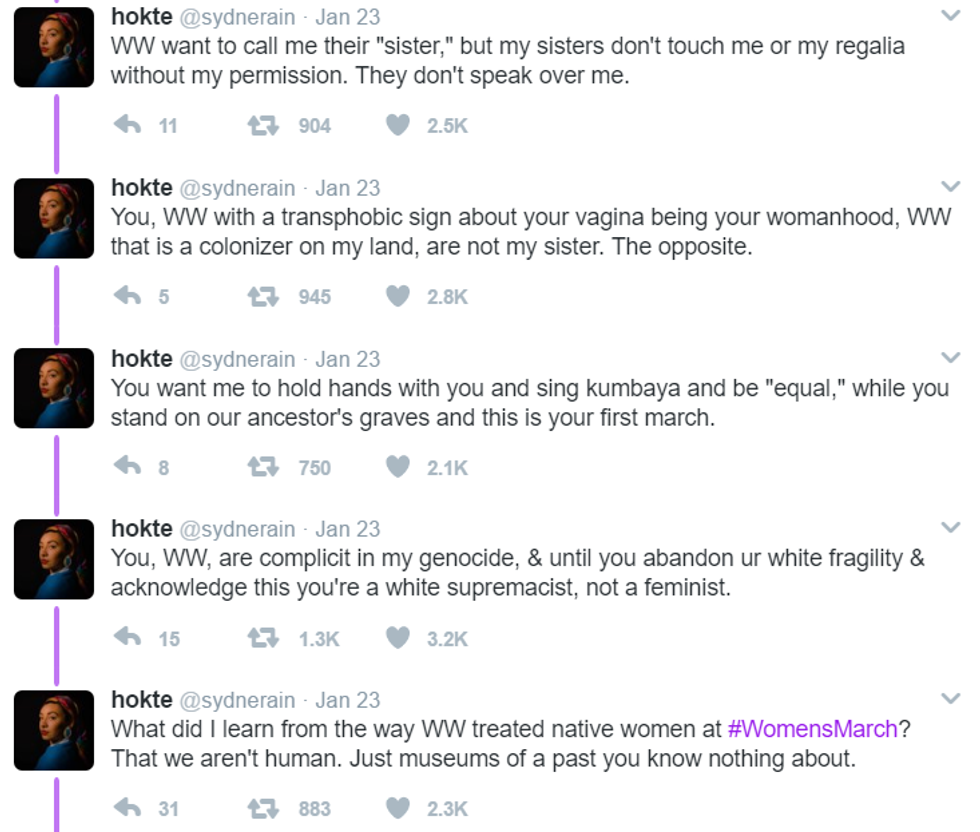

A look at the event’s Facebook page comments and other social media traffic associated with the rally indicates a large number of attendees who felt that the program was able to foster empowerment and unity; however, a highly overlooked but certainly still crucial voice that also appeared in response to the march was dissatisfaction with the ‘whitewashed’ demographic of the rally, the centering of the rally on cisgender women and cissexist standards, and the inclusion of nationalistic and patriotic elements to the program.

Be The Change Alliance, founded by Gwendolynn Combs, sponsored and organized the Women’s March For Arkansas. The platform of the march and rally was intended to be an intersectional one that would amplify the voices of marginalized women in various communities, as indicated by the Facebook page:

“We support the advocacy and resistance movements that reflect our multiple and intersecting identities. We call on all defenders of human rights to join us. This march is the first step towards unifying our communities, grounded in new relationships, to create change from the grassroots level up. We will not rest until women have parity and equity at all levels of leadership in society. We work peacefully while recognizing there is no true peace without justice and equity for all.”

However, a significant number of responses from women of color and trans women, many who attended the rally and many who deliberately chose not to, may reflect a different reality.

Like the vast majority of the Women’s March events that happened throughout the world on January 21, the Women’s March For Arkansas featured a large number of signs using vaginas and uteruses as feminist symbolism/imagery---a recurring motif in feminist art and feminist movements that center on cisgender women. Many of the signs that had phrases like “Pussies grab back!” were intended to be a direct response to Donald Trump’s misogynistic comment from a video of his private conversation on the set of Days Of Our Lives where he says about women, “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.”

However, many of the signs featured phrases such as “No Pussy No Power” and “Uteruses Before Duderuses”, which can easily be perceived as promoting a limiting, objectifying, and inaccurate perspective on womanhood and actively alienating transgender women from the movement. Though there have been many arguments made on the importance of reproductive justice, responses from communities of color and the transgender community have asserted that the reproductive rights movement should move from focusing largely on the reproductive organs of cisgender women, to broadening the definition of what is considered “reproductive justice”.

#WomensMarch activist remember

-not all women have vaginas

-not all women have periods

-not all ppl with vaginas are women

-cissexism is bad

— a trans™ (@CommonTransKid) January 22, 2017

Not only that, but Trump’s “pussy” comment highlights his objectification of women, sexual predatory behavior, and his promotion of sexual assault---none of which are exclusive to only women with vaginas. Transgender women, particularly transgender women of color, face a higher risk for sexual violence than their cisgender peers, as well as the highest risks of homicide compared to other marginalized groups.

Other criticisms of the Women’s March in Little Rock were concerns about overtly pacifist and patriotic overtones, with concerns that the march would not serve the function of a protest--that is, to create a disruption in order to call attention to a cause or demand. The inclusion of the oath appeared to cause discomfort in some protesters who saw cognitive dissonance in a rally that is in opposition to the Trump administration encouraging the crowd to swear loyalty to the United States constitution.

In addition, some of the supporters of the Trump administration include the KKK and the modern white nationalist movement (often referred to as the “alt-right”), and the promotion of racist fear-mongering was one of the major reasons that Trump was able to snag the presidency. This and the fact that the Women’s March For Arkansas, like the majority of other Women’s Marches that took place in the United States, appeared to be overwhelmingly white, indicates a disparity between the largely white mainstream liberal feminism movement and the actual pressing issues affecting American women. In addition, the majority of the rally's attendees were Little Rock residents; however, black residents make up 42% of the population of Little Rock, while black attendees of the rally didn't make up even close to that amount. Exclusion, whether willful or accidental, appears to be the only explanation for many.

It is a well-known fact that the statistics ultimately point to white supremacy as the deciding factor in the 2016 election, which has continued to complicate solidarity between white women and women of color during the Women’s Marches--including the one here in Little Rock. It was, after all, 53% of white women who voted for Donald Trump, compared to a staggering 94% of black women who voted for Hillary Clinton, and an overwhelming Clinton majority in every non-white demographic.