Happy Women's History Month! This is the first of what will be three to four blurbs throughout March about women who contributed awesome things to society.

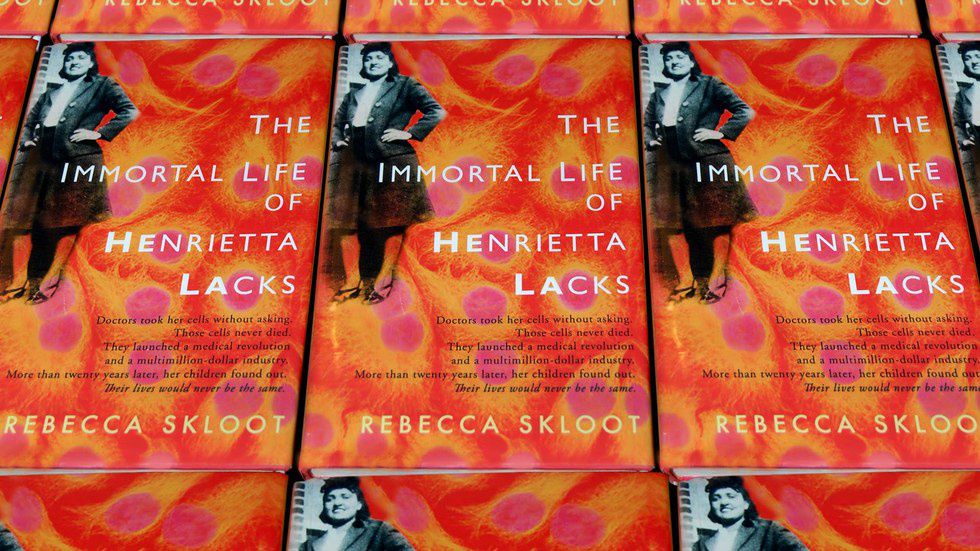

First up is Henrietta Lacks. Author Rebecca Skloot's biography, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, has landed on just about every "MUST READ" list, especially for students going into the science and health fields. Like many women of her time, and especially as a black woman, Lacks was the victim of a society dominated by men seeking power and wealth. She was deceived, and others were able to profit off of her, using the "the advancement of science" as their excuse. So, let's start from the beginning.

Henrietta Lacks was a poor African American woman who grew up on a Virginian tobacco farm during the Great Depression and World War II. At just 30 years old, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer after feeling a "knot in her womb." In 1951, she went to Johns Hopkins for radiation treatment, during which doctors removed cancerous tissue samples without asking or informing her. Less than a year later, Henrietta Lacks died after months of severe abdominal pain and blood transfusions.

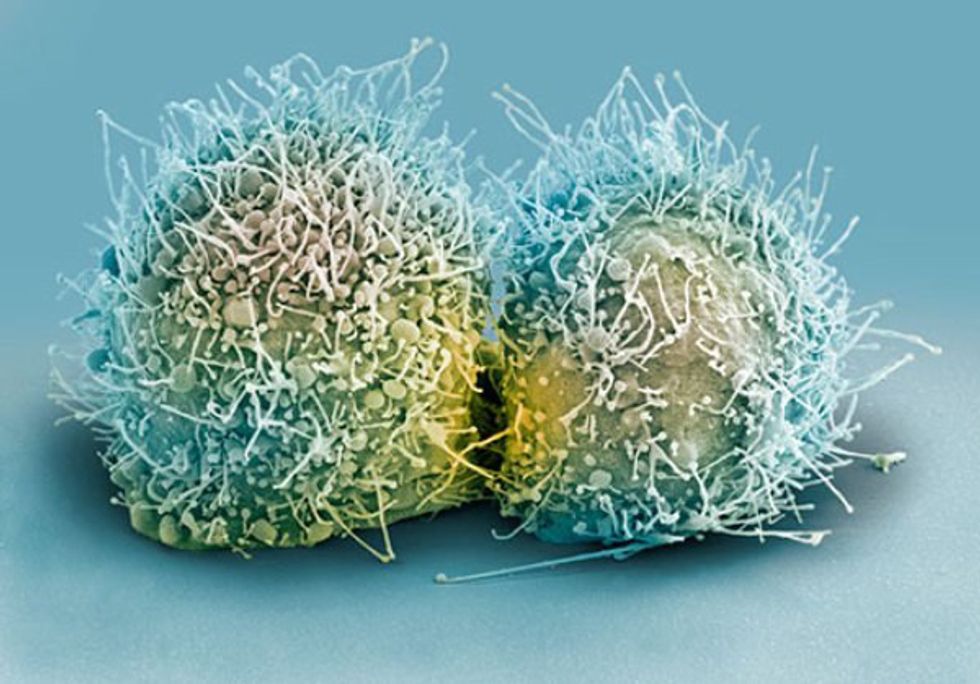

The tissue samples were given to Dr. George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that the cells were unique; they divided faster than any cell he had seen before. Furthermore, they could survive much longer than any other cell lines used in research at that time. Because they just kept multiplying without dying, her cells were said to be "immortal."

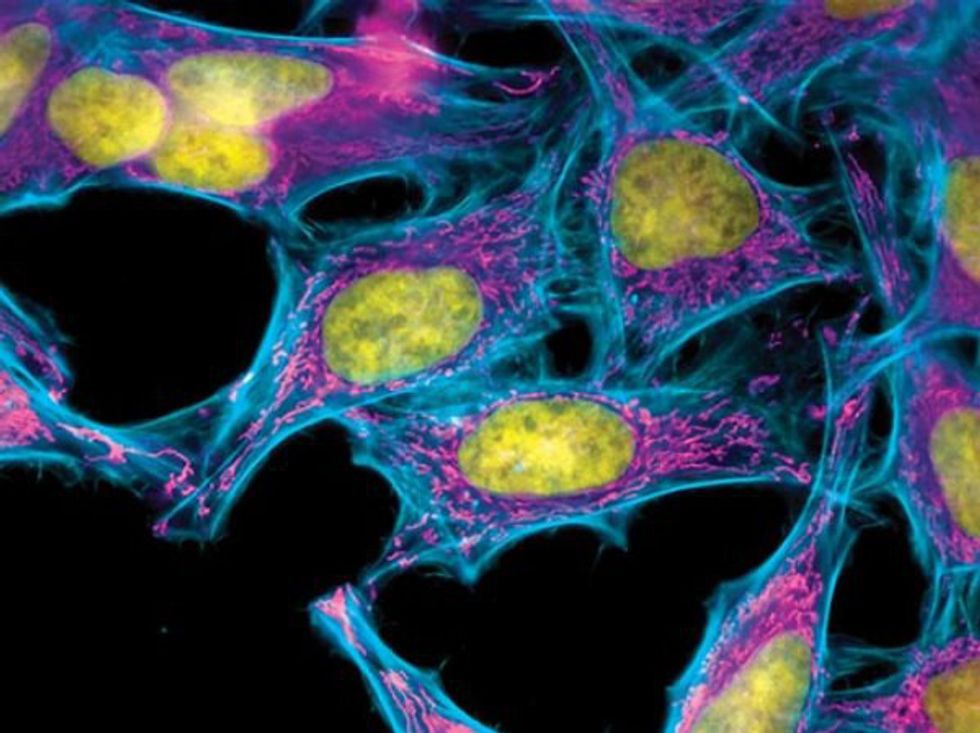

Gey wanted more samples to work with. After Lacks died, Gey instructed his assistant to go find her body in the autopsy room and remove more tissue (without asking the family). Gey isolated a single cell and divided it many times, until he had an entire line of identical cells. He named them HeLa cells, for the first two letters of the patient's first and last names. Because scientists all over the world had been struggling to grow human cells in culture, HeLa cells were in high demand. Scientists and pharmaceutical companies mass manufactured the cells and made billions of dollars by selling them to research labs all over the world. HeLa cells are still one of the most popular cell lines to use in research today, and they can be found in almost every cell lab across the world.

So profiting off of someone's body sounds pretty terrible, right? Well it gets worse:

Lacks' family was not made aware of any of this until 25 years after Henrietta died. After finding breast and prostate cells that closely resembled HeLa cells, scientists called the family and wanted a DNA test to see if their cells were in fact HeLa cells. The husband had third grade education and had no idea what a "cell" even was. He thought doctors were trying to tell him that his wife was alive but had been kept in a lab for 25 years. The family was extremely poor and couldn't even afford health insurance. Yet, rich white men in power were getting filthy rich from a piece of tumor that they didn't have permission to take in the first place. Further, the family only found out in 2013 (by Skloot, as she was writing the book), that scientists had published the entire DNA sequence of the cells, jeopardizing the privacy of Lacks' kids and grandkids. The family received no financial compensation for decades, but I am unsure whether or not this still holds to be true.

HeLa cells have been an invaluable tool for the advancement of science and medicine. In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Skloot says:

They were essential to developing the polio vaccine. They went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to cells in zero gravity. Many scientific landmarks since then have used her cells, including cloning, gene mapping and in vitro fertilization.

Yes, the cells helped us achieve great milestones. But at what point are ethics more important than scientific gain? Did we need to take advantage of a poor black woman and her family in order to promote medical treatment?

While science advanced via HeLa, so did the field of medical ethics and patient rights. Informed consent and other research privacy laws (like how to properly use genetic material in research) were initiated through many court battles between the family and scientists. Many prestigious research institutions like the NIH and Johns Hopkins have recently recognized the Lacks family and apologized for any wrongdoings.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a must read for many reasons. For current or future scientists, it reminds us that our specimens are a privilege to have. We do not have the right to samples, so we must treat each one respectfully. We must be respectful toward the organism and their loved ones, whether they be fruit fly or human. When working with humans or their specimens, privacy matters more than anything else. People trust us as scientists to fix the world's problems, and we must not take advantage of that trust. We must abide by rules and regulations to ensure the safety and security of anyone who may be directly or indirectly involved. Even if you're not in the science or health fields, Henrietta's story is a much needed lesson about power, race, gender and class.

A poor black woman changed scientific research forever, and yet her story is widely unknown. I chose Henrietta Lacks as my first historical female figure to write about because she hugely impacted a field I am so passionate about but never got the recognition she deserved. Her message, legacy and especially her cells will live on forever.