Animated movies’ favorite subject when it comes to Mexican culture is Día de los Muertos, because, of course, it’s a colorful holiday featuring sugar skulls and an abundance of festive foods. Día de los Muertos is also a beautifully sentimental tradition of remembering those who have passed. It is not a giant funeral; it is not sullen or morose. The day is full of heart, joy, spirituality, hope, and pride—as is elemental of the Mexican spirit. There is nothing wrong with education and demonstrations of Día de los Muertos in the form of colorful Pixar and Guillermo del Toro films, but richer and deeper stories and legends are also characteristic to Mexican history and culture than that one special holiday.

For instance, have you ever heard of Las Adelitas? It is not a Mexican restaurant…well it may be, but that’s not what precedes the name. Las Adelitas were Mexican female revolutionaries, synonymous today with las soldaderas.

The first thing to understand about the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) is that it may not have truly ended. Violence between citizens and federal troops ensues to this day, although perhaps not as overtly (due to the suppression by cartels and dictators). Historians generally cap the revolution at 1920, after Álvaro Obregón was elected following the assassination of his former ally Venustiano Carranza, but I may be jumping too quickly ahead.

To sum things up briefly, the Mexican Revolution began after a man named Francisco Madero declared a revolt against the dictator president Porfirio Díaz. Madero had been arrested for attempting to run against Díaz to prevent Díaz’s 7th term, and when released Madero called for a rebellion against Díaz through his publication of Plan de San Luis Potosí. Even though the revolt failed, others were inspired by Madero’s courage. In the North, Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa raided government forts while Emiliano Zapata fought against political bosses in the South. The following year, in 1911, the revolutionaries took over Juarez, made Díaz step down, and then Madero became president (1).

Unfortunately Madero did not move fast enough in restoring stolen land to the Native Americans, so former friend Orozco rebelled, followed by the U.S. government (who were concerned about business investments). A whole other revolution sparked against Madero, this time featuring the late Porfirio’s nephew, Félix Díaz. This Díaz fought federal troops in Mexico City by the command of Victoriano Huerta. In 1913, Huerta was made president after the arrest of Madero. Then, yet another rebellion emerged against Huerta via formerly mentioned Villa, Obregón, and Carranza. This is where our soldaderas come in.

Under President Victoriano Huerta, men were drafted into fighting against the rebels. Women’s husbands would have potentially left them and their children alone during a volatile and unpredictable war, therefore to keep families together women accompanied their husbands (debatably voluntarily) at first. Whether or not they wanted to, soon women were also drafted under Huerta’s rule. There are two separate classes of these females, the first being la soldaderas, who did not actually fight in hands-on combat during battles (both for federal and rebel armies).

Soldaderas may not have fought on horseback themselves, but they proved to be swell companions to the male troops: as chefs, working power mills, carrying equipment, transporting goods, setting up campsites, and—for those who were unmarried—sometimes as prostitutes. These homemaker-type roles were not restrictive, however (hence prostitution). The women also performed duties including raiding enemy corpses for any helpful information or resources as well as serving the troops as nurses during combat. Perhaps the craziest role they filled would have been ammunition smugglers, since border patrol would not have placed them in any affiliation with the war and suspicious would be eliminated.

Maybe you saw this one coming, but it deserves its fair share of the story: since soldaderas followed behind troops, they were oftentimes raped and killed as a strategy for enemy fleets who knew that if the women were sparse, so were the resource networks. Soldaderas did not last throughout the revolution once food became scarce and the armies had to focus on their central components: the actual troops.

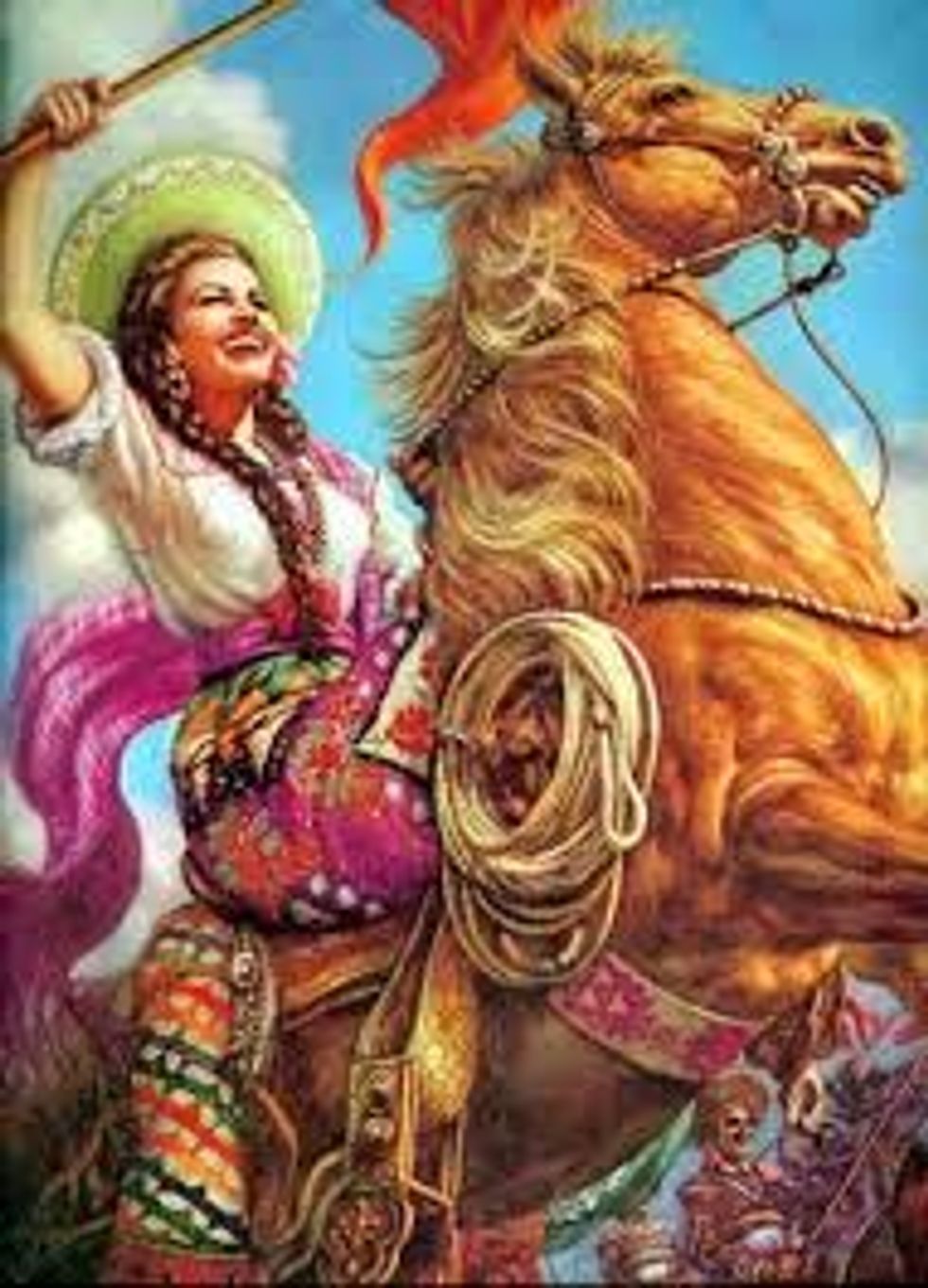

Now for the alternative status of women involvement in the Mexican Revolution: the female soldiers. There were actual women who fought in battle, and they were not called soldaderas, as these women were of a higher class who could afford horses to ride on during battle. The female soldiers were also “recognized members of the military who could advance their position in the army” (2), although apparently nobody ever heard of or acknowledged a woman, or a coronela, rising to the position of general (3). They sweat, bled, fought, and died next to the men by choice.

The phrase la adelita originates from a ballad composed in representation of the legendary roles both the actual soldiers and soldaderas valiantly fulfilled:

In the heights of a steep mountainous range

a regiment was encamped

and a bright woman bravely follows them

madly in love with the sergeant

Popular among the troop was Adelita

the woman that the sergeant idolized

and besides of being pretty she was brave

that even the Colonel respected her.

And it was heard, that he, who loved her so much, said:

If Adelita would like to be my girlfriend

If Adelita would be my wife

I'd buy her a silk dress

to take her dance to the quarter.

If Adelita would leave with another man

I'd follow her by land and sea

by sea in a war ship

by land in a military train (2)

Obviously the not-so-sexy parts about these women were erased for the dreamy, sensual, male-centered objective of the song, nevertheless La Adelita is what the revolutionary women can be remembered as. Of course, Pixar can do its thing and sugar coat the heck out of it, but let’s not in any case forget all of the kickass mujeres of the Mexican Revolution.

1. https://www.britannica.com/event/Mexican-Revolution

2. http://umich.edu/~ac213/student_projects06/joelan/whysoldaderas.html

3. https://www.latinlife.com/article/1337/strong-women-of-the-mexican-revolution-adelitas