Today, William Haines is not the gay icon that he should be. But his story could be—and should be—the stuff of LGBTQ pop culture lore. As Lara Fowler (who is currently writing a biography on Marion Davies, Haines' one-time co-star and longtime friend) once told me on Twitter, he was "so unapologetically out and proud. He really should be better incorporated into the LGBTQ pantheon than he is--I feel like people just don't really know him that well anymore."

Haines' life is the perfect story for Pride Month: a man who, despite the challenges, lived proudly as an openly gay man in Hollywood before the social conventions of being gay even existed. Such a story is relevant today; even as these social conventions are very much established in today's society, they are not yet fully accepted (as the live-action "Beauty and the Beast" proved just last year.) Between choosing to hide or live authentically, Billy chose his true identity.

But back then, there actually was an openly gay culture in Hollywood—a culture in which William Haines, along with Jimmie Shields, his lover of 50 years, lived with pride as who Joan Crawford declared as "the happiest married couple in Hollywood."

This is his story.

Finding Himself in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village was many things during the 1920s.

It had a reputation as a "Bohemian Mecca," while also acting as a haven for anyone for who would be considered by society as a "sexual outlaw." As you may guess, this included gay men and women, but also anyone—male or female—who wanted to break social conventions and have a sex life outside of the sanctity of marriage. But Greenwich Village was very progressive in today's view as a playground where homosexuality was not only accepted, but also respected. And as a result, the Village cultivated a vibrant (and not-so-subtle) gay culture in the 1920s that predated Stonewall (and the gay liberation movement that followed) by 40 years.

It was where people (predominantly white middle-class youth) flocked to after work or on weekends, as it was easily accessible by subway and it offered places to "escape." A bohemian carnival, the Village was lined with speakeasies, cabarets, and tearooms (a number of which catered to gay patrons.)

It was seedy, but that was part of its allure: Greenwich Village was a place where one could experience the forbidden: nude art, excessive drinking, burlesque shows, etc. But most importantly, in the Village, people felt free to love without the sanctity of marriage.

And this was all waiting for William Haines, who had lived in New York once before, but family obligations brought him back home to Staunton, Virginia. So when the time was right, in 1919, the restless Billy bid farewell to his hometown for good, and settled right back in.

He landed a job as an assistant bookkeeper and moved in with two roommates who would have an influence on Billy's lifestyle and identity as a freewheeling gay man: Mitchell Foster and Larry Sullivan.

Billy, as you'll later see, was very much inspired by Foster and Sullivan as a couple. Both were very comfortable and confident in their self-identities as openly gay men. Out in the Greenwich Village social scene, it wasn't much of a secret that Foster and Sullivan were a couple; they didn't hide, but they didn't exactly exclaim it loudly either. Their relationship would serve as a model that Billy would later emulate in his future long-term relationship.

Haines even idolized Mitchell Foster, who was ten years his senior. It's easy to see why: Sullivan was Billy's age, while the older Foster was someone who Billy looked up to as a mentor. And he was the one who cultivated Billy's appreciation for antiques (which will become important later on...)

Among William Haines' other friends were two men who were also a couple: a 23-year-old Australian artist named Jack Kelly and a 17-year-old British vaudevillian named Archie Leach. Like Foster and Sullivan, Kelly and Leach were also nonchalant about their sexuality, and, like Haines, they would both eventually end up in Hollywood. Jack would be reinvented as Orry-Kelly, one of the top costume designers in Hollywood. As for Archie? Well, he went on to become a household name as actor Cary Grant.

The people Billy Haines associated with perfectly represented today's image of youth in the Roaring Twenties: an easygoing and carefree generation who ignored societal standards and norms. In the Village, Haines found a community of people who defined themselves fluidly, similar to how we approach self-identities today. As podcaster Karina Longworth (who discussed Haines in an episode of her podcast) put it:

"You were either what straight society deemed acceptable or you weren't...and if you weren't you could either pretend that you were or you could find a community in which (at least for part of the day or night) you wouldn't have to hide and you could...do what you want to do without conforming to a specific label."

So, like his friends, Haines never felt pressured to hide his sexuality during his time in the Village (nor did he really feel like he had to.) He would find a similar culture of acceptance in Hollywood, but with more challenges.

Going Hollywood

So how did William Haines get to Hollywood?

In 1922, the Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood ran a contest called "New Faces," and Haines, who had jumped from bookkeeping to modeling in New York, found himself being crowned as the male winner. Haines, along with Eleanor Boardman, the female winner, were offered Goldwyn contracts when they arrived in Hollywood in March 1922.

Boardman was quickly cast in substantial roles, but Haines didn't find as many doors open for him in the same way. In his first three years in Hollywood, he was only cast in very minor roles, but Haines worked on developing his film persona as a "wisecracker." In fact, he had even demonstrated this persona on his first day in Hollywood when he walked into the executives' office at Goldwyn Studios and announced, "I'm your new prize beauty."

But it was his looks that had won him the contest, as personal beauty was typically a top priority in selecting film stars during the silent era and beyond. Longworth's assessment of Haines' looks was spot-on when she described the Hollywood newcomer as having "smiling eyes" and "a little bit of Paul Rudd in his dark hair and impish grin."

As Goldwyn Studios was bought and was merged into what would become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios (MGM), Haines was still not where he wanted to be in his film career, but he had a plan. He took it upon himself to prove himself as a star by first establishing himself as a Hollywood social animal.

He "dated" other female stars, escorted female friends to parties and speakeasies, and even spotted men and women with the potential for stardom, including Clark Gable and Joan Crawford. Crawford, who had a lifelong friendship with Haines, attributed her success to his guidance; it was Haines who helped Crawford lose her Oklahoma accent and build herself as a star by getting photographed on the Hollywood social scene.

But while Billy Haines was busy elevating his star status and "dating" MGM actress Norma Shearer, he also "got busy" with another fellow MGM star: Ramon Novarro. Around this time, Billy became more and more popular around town, as other stars thought of him as fun to have at parties, but there was one actor he was unpopular with: Lew Cody.

One day in 1925, Cody, who had an ongoing feud with Haines, marched into the office of Louis B. Mayer, the head honcho at MGM, to inform him that Navarro and Haines were not only seeing each other, but they had also been frequenting a nearby male brothel.

Upon hearing this piece of news, Mayer probably struggled between letting his personal beliefs influence his business decisions. Haines' biographer, William J. Mann, describes Louis B. Mayer as slightly homophobic, but suggests the mogul's attitudes on homosexuality weren't the reason behind his growing distaste for Haines and Navarro. According to Mann, Mayer also complained about both stars for years to Irving Thalberg, a producer at the studio and Mayer's right-hand man. The mogul was mostly concerned with their behavior reaching the press and creating a scandal, but he was also worried about their relationship tainting the Navarro's image as a masculine hero on screen.

And while Mayer began to view Billy Haines as trouble to the studio, this incident only damaged Haines' relationship with Navarro—the latter feeling obligated to cut ties with the former.

Ultimately, it was decided that Navarro was too valuable to let go of, being that he was popular with audiences for his "Latin lover" and "swashbuckler" roles. Irving Thalberg stepped in to make sure that Haines was spared too—and the actor would later write that Thalberg always had his back.

Surviving this incident in 1925, 1926 was a landmark year for William Haines. He finally landed his breakout role in a silent drama called "Brown of Harvard," in which he plays a carefree college football player and ladies' man at Harvard. The box-office success of the film launched Haines into stardom and cemented a formula in which Haines would play wisecracking, and often arrogant, "college man" roles in both silent dramas and comedies. And his characters would always get the girl in the end.

One exception to this formula is a personal favorite of mine: the 1928 silent comedy "Show People" in which he co-starred in with actress Marion Davies. It was the first silent film I had seen that was not a Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton film, and upon seeing William Haines for the first time as the flamboyant and wisecracking Billy Boone, I couldn't help but question "is he…?" But throughout his film career in the 1920's and '30s, a time in which homosexuality was not "the norm," he was able perform as romantic leads in such a way, and audiences thought nothing of it.

It was 1926 that boosted Haines' career in Hollywood, but something more meaningful also came his way that year: he met Jimmie Shields.

The Hollywood romance of William Haines and Jimmie Shields

While on a trip to New York, just before "Brown of Harvard" was to make him into a massive star, William Haines met Jimmie Shields, a 21-year-old former sailor in the Navy, and what initially began as a whirlwind romance turned into more when the time came for Haines to return to Los Angeles. Lovestruck, Haines pleaded for Shields to come with him, promising he would try to find the former sailor work in Hollywood. And Shields agreed, as in the past year he been honorably discharged from the Navy due to health reasons and was currently unemployed.

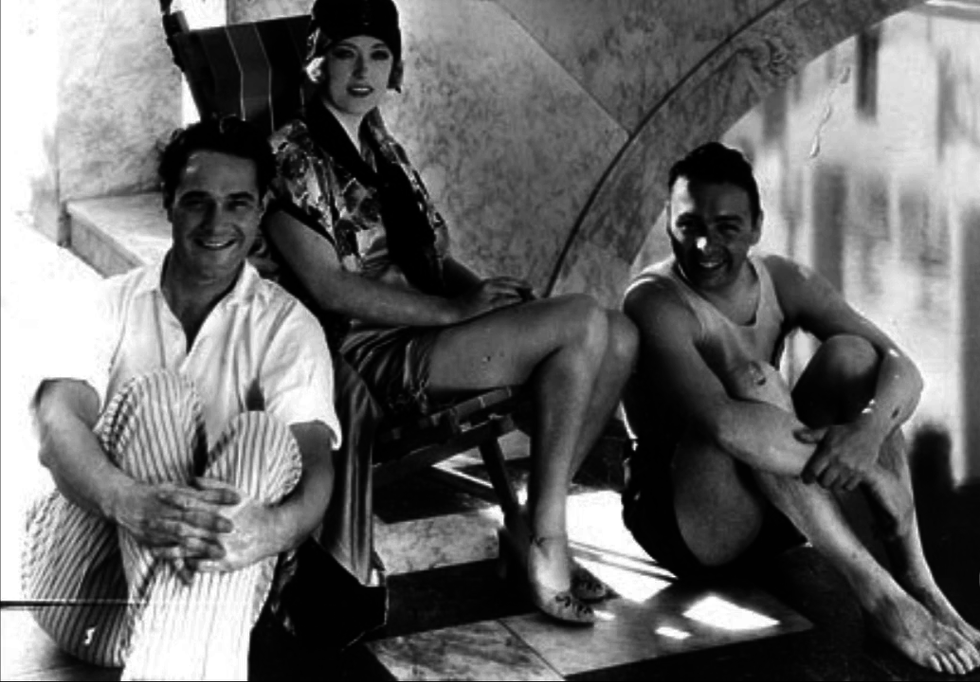

Back in L.A., Haines and Shields lived together openly just like Haines' friends Mitchell Foster and Larry Sullivan from his Greenwich Village days. And, surprisingly, they were accepted as a couple by almost everyone when going out on the Hollywood social scene. They were frequently invited to Hollywood parties at San Simeon, the estate of actress Marion Davies and William Randolph Hearst, who, like Haines and Shields, were also in what was considered back then as an "unconventional relationship"—unbeknownst to the public, of course.

Hollywood was, and sometimes still is, a community that lives in a bubble; anyone who was an outsider was not "in-the-know" of what actually went on there, and what was fed to them as the truth was fabricated by studio publicity departments. Which is why Haines' sexuality was became somewhat of an inside joke in entertainment journalism at the time—which the major studios had considerable control over—as they always knew the truth whenever Billy dodged questions about his love life and gave reporters tongue-and-cheek answers that would eventually make it to print.

Wisecracking, in another sense of the word, allowed Billy Haines to walk a fine line between telling the truth about himself and living authentically. Many times he claimed that he was engaged to a comedienne named Polly Moran—who was also in on the "joke."

So while Haines lived openly with pride in Hollywood, American filmgoers had no idea that he was gay. As long as it was kept out of public knowledge, Louis B. Mayer felt that he had no reason to let go of Haines.

Meanwhile, on the "inside," Haines and Shields not only lived together, but they also considered themselves very much married, and continued to live that way for decades—even though they weren't married on paper. They bought a two-story Spanish home just off Sunset Boulevard and made a project out of redesigning it. And this was socially unthinkable anywhere else in the country at the time—but then again, the same was true for a man and woman to cohabitate outside of "conventional" marriage.

Haines' Crossroads Moment

Haines, unlike a number of stars, smoothly survived the transition from silent films to sound films. Mayer and Thalberg felt confident that his rich voice and acting abilities were suitable for a male star as the studio started making "talkies." And audiences agreed. He still continued as a box-office draw, and his wisecracking persona of his silent films easily translated into films with sound.

However, he would soon find that his film career would not last much longer due to a number of things. The growing influence of the Production Code in Hollywood posed a threat to the major studios, as did the rise of publications such as The Hollywood Reporter that, unlike other Hollywood publications, chose not to publish studio press releases or stories fabricated by studio publicity departments. What's worse, they also did not hold back from writing honest stories that could incite scandal.

The Roaring Twenties had come to a crashing end (pun intended), and the liberating attitudes from the decade were soon to fade with it. Both the country and the film industry also entered a moral panic in the early years of the Great Depression. All of these forces in motion, as Haines would find out, meant bad news for his career in Hollywood.

Beginning around 1930, the major film studios began using the morally-driven Production Code to write "morals clauses" into their stars' contracts to keep their public behavior in check. Unlike other top stars who willingly signed under the assumption that their star power kept them safe, Billy Haines tried to get this part of his contract removed by not signing.

As a consequence, MGM penalized him with a two-year deal rather than the five-year contract that he refused to sign. To make matters worse, when his films started to perform sluggishly at the box-office, MGM attempted to reinvent Haines from his persona as a college boy into an adult leading man. Which meant, unlike his past roles, that he had couldn't let his true personality shine on-screen.

One day in 1933, Louis B. Mayer summoned Billy Haines to his office and presented him with an ultimatum. "You're either to drop that boyfriend of yours," he warned, "or I'll cancel your contract."

For as long as he had been in Hollywood, Haines had attempted to replicate his experiences from Greenwich Village by frequenting similar gay nightlife spots in L.A. (such as speakeasies and cabarets) But unlike his time in the Village, these spots became increasingly more likely to be targeted by police raids beginning in the 1930s. By 1933, Haines and Shields had been arrested several times during such raids, (one of which was even at a local YMCA center) and each and every time, Mayer had to swoop in to make sure this stayed out of the press.

By this point, Mayer had enough of Billy's "risky behavior," especially as his films were struggling at the box-office. What's more, Mayer was pushing for Haines to get "sham married" and wed another star to help build his new persona as a adult romantic lead.

This was something that Haines, who felt his career slipping, had once considered as a desperate effort to save his career. In doing this, he could appeal to Mayer, who preferred gay stars under contract at MGM who "played the game"—meaning they would sacrifice their love lives and true identities and marry female stars to help create the public image that the studio publicity departments envisioned for them.

He had even proposed to actress Anita Page, and she needed guidance on whether or not to proceed. Unsure of what to do, she went to Louis B. Mayer, who oddly served as a father figure to many of the stars at the studio. "Don't you know what he is?" Mayer asked her. She responded, "All I know is he's my friend."

That was true—like Joan Crawford, Haines also had a close friendship with Page that lasted a long time. But she felt marrying Haines was not the best choice for either of them, and she told him that she was "not his Anita."

Perhaps this experience helped Billy realize the gravity of what he almost did; even if this not true, Billy seemed to know what he wanted during this meeting with Mayer. With an ultimatum being forced upon him, Billy probably saw himself at a crossroads in which had to choose between the paths that two of his friends from his Greenwich Village days had taken. He could either live authentically with the man he loved, like Mitchell Foster, or he could "play the game" as Cary Grant would go on to do.

And Billy chose Jimmie.

William Haines, Post-Stardom

Even with his film career over, William Haines still remained famous...as one of the top interior designers in Hollywood! After leaving MGM, he went on to turn his turn his long-time hobbies for home-decorating and antique collecting into his new profession. He became part-owner of an antiques shop in a prominent part of Los Angeles, and then founded his own interior design company (which still exists today!)

His clients often included Hollywood stars such as Joan Crawford, Marion Davies, Carole Lombard, and many others, but he also went on to design for the Reagans in the White House, as well as Walter Annenberg, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Billy probably never thought of acting, interior design, or any other career as his calling, as he had never aspired for any particular career. He lived his life like a journey with stops along the way; he became a bookkeeper at age 20 in New York, a Hollywood actor at age 22, and an elite interior designer at age 33.

His true calling in life was in discovering himself and living authentically. And he found that in Greenwich Village, in Hollywood, and in his marriage to Jimmie Shields. William Haines represented gay pride before gay marriage was legalized, before the Stonewall Riots and the modern gay movement, and before the term "gay" was even used at all.

Despite once being a huge star in Hollywood, his name has faded into obscurity. Yet, the courage he demonstrated in sacrificing his fame to live a genuine life with his true love represents what it means to be a modern-day Gay Icon.

As for Shields, his life with Haines also meant everything to him. Haines had passed away from lung cancer in 1973 at age 73. Two months went by following his death, and Shields was still distraught; he had even told a friend one night, "I just can't go on without Billy." That same night, he passed away in his sleep from a prescription overdose.

When Billy Haines had fallen in love with Jimmie Shields in New York, the silent film star decided that he couldn't continue on without his new love. And after fifty years together, Jimmie Shields felt the same way. He was interred in his final resting place in the Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery—beside his husband, William Haines.

To learn more about William Haines, check out:

"Wisecracker: The Life & Times of William Haines" by William J. Mann

Episode 60 of the podcast "You Must Remember This"

And tweet me your thoughts about William Haines' story @missjulia1207.