Chances are that out of the last 10 films you've seen, the majority of them involved blood, violence and death. Violence is one of the most common elements seen in media, with action heroes almost always prominently displaying a firearm or engaging in brutal, break-neck combat. Comparisons are often drawn between tolerance of violence in films and television with the aversion that many American audiences have from sexual content in media, especially when it comes to children's exposure to that material.

I want to look at the sense of violence in media and how many films use violence as their core mechanic, but not quite as their core method of storytelling. There have been a lot of complaints over the years dealing in the abundance of bloody or violent content that continues to saturate the media space, but I'm not saying whether they are right or wrong. I think these arguments contain valid points to be put into the mix and discussed. I want to think more about why and how we've allowed violence to become the central motif behind so many films.

There's a concept out there called "historicism," and it's the idea behind certain interpretations of literature that places a text inside of a historical, geographical, or cultural context, stating that there's very specific meaning tied to those particular confines under which the work was created. It becomes really interesting when you take what's happened there and apply it to a different medium like film.

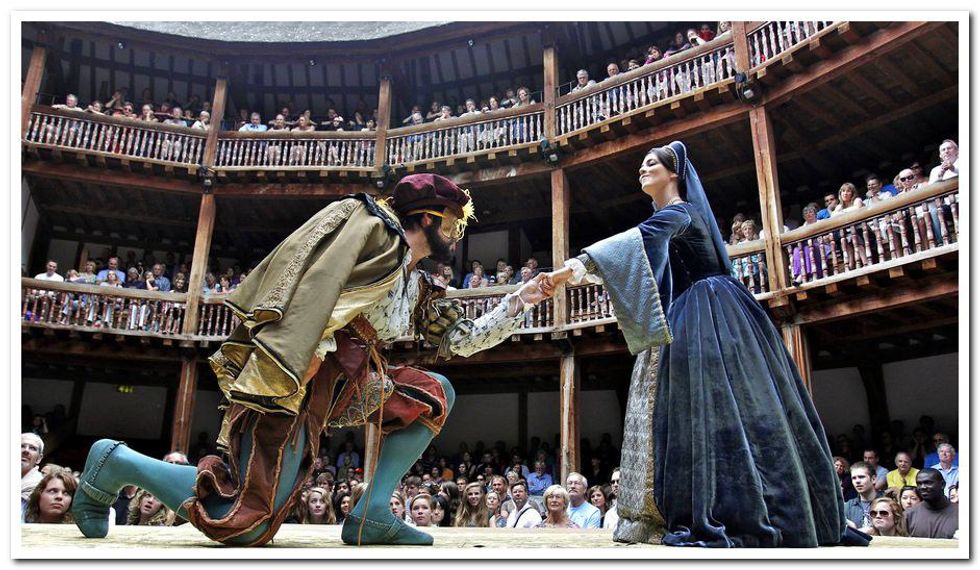

So let's wind the clocks back a bit. You can look at the plays of Shakespeare's time and see they held a business imperative. They were in an economic environment, patrons funded the productions and expected a certain level of success and they had to find some way to reach their proper audience. Also, plays were not the only form of entertainment at that time. The Globe Theater, where Shakespeare's plays were performed, also indulged in other types of activities, most notably: blood sports. It was extremely popular to bring in a bear and a dog and have the two fight. As you can probably imagine, the show was gory. That kind of spectacle was incredibly popular, and it brought about a need to find a way to have entertainment that was fictional yet could somehow convince someone who loves seeing bears rip dogs apart to go to the theater. This is why we've wound up with works like "Titus Andronicus" and "Macbeth." Stagehands used to fill buckets with pig's blood that would be thrown on the actors on the stage to really play up the more lurid and sordid aspects of the story.

Of course, there were also comedies that were filled with sexual innuendo. Those elements brought in the rabble because that was really the key audience of these shows, it wasn't just high minded as we present these plays today.

It's with this in mind that I think we look at the role of violence (be it shooting or swordplay) in today's films. It serves as a commercial means to meet the audience. When you consider sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars are being invested into these films, it's easy to see that we've established a kind of form over time. I'm not saying it's a bad thing.

It's something called artistry. Not art.

When you have all of these business parameters that you have to navigate and negotiate, but still want to create something that is a work of art, that process — which I find really fascinating — is really one of the most admirable aspects of what you see in film development. I think it's fair to argue about whether or not we have too much violent content in films today, or if we're really just resting on our laurels of something that has proven to be successful year after year. However, you can also look at it in terms of tradition. It's similar to musicals, where it doesn't really make sense why people suddenly break into song after speaking normally only a moment before. The idea is having a story, and it breaks up into these segments that are transitioned by violence as part of tradition, similar to the five act structure of a Shakespearean play or the way you put together and Italian or an English sonnet.

What I mean by all of this is we have this tradition that we work with and that we work within which slowly changes over time. One of the more interesting things, I think, is the fact that —returning to Shakespeare's era for a moment — Shakespeare's plays weren't necessarily that popular. In fact, some of the most popular plays of Shakespeare are almost indecipherable today. "Pericles" was the most popular play he had and due to the fact that they likely lost the original language, we fail to figure out now why exactly it was so good. The most popular play of that era was "The Spanish Tragedy." There's nothing really remarkable about the language, and there really isn't much poetry to be found in it. It's read more or less as a historical document, but it is one where a man cuts off his own tongue and roughly 20 people are lying dead on the stage by the end.

So when we look at something being wrong with our society today and our interests and fascination with violence, remember that it actually has a tradition of subjects and texts that we still study in our best universities.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion