Donald Trump has deliberately chosen to challenge the rules of politically correct speech.

I will not belabor the pushback to his message—“This hateful rhetoric must end”—although I totally agree. Instead, I want to focus, today, not on the Man With Suspiciously Orange Hair, but on a majority who gets far less press than he does.

The NPR Politics Podcast, in their Sept. 1 weekly roundup of news, noted a trend that my friends, Oscar and Delicia, told me about last week.

While Asma Khalid was discussing the national conversation about immigration, she remarked, “Polling consistently shows that a majority of Americans, sometimes upwards of two-thirds of Americans—of all races—do believe in some sort of immigration reform that would allow for some sort of legalization, if not permanent citizenship, for folks in the country, who are not committing crimes.”

Two respected polling firms, Pew Research and Gallup, confirm this claim.

Last week, I decided to write about immigration—not on a national level, but from on a local level. So I texted Delicia. She herself is a U.S. citizen, but her dad is from Mexico, and I thought she would know someone I could interview who has emigrated. She volunteered her husband, Oscar, telling me, “He’s a good sport,” when I asked if he really wants to talk to me.

I asked Oscar, an undocumented resident, what he’s felt from Americans: has he felt racism and hostility, or openness and respect?

He said that he has lived mostly in Spanish-speaking communities, so he doesn’t deal with other people much. In both Texas and Kansas, though, he felt people were kind and friendly. He knows that there are people who are racist, but hasn’t encountered that often.

Delicia added that she has rarely felt that anyone treated her differently because of her race. Growing up, she said, she knew a family in her neighborhood identified with the “KKK”, and she always avoided that house. “I was always afraid they’d come out and slap me or hurt me or something.”

Otherwise, Delicia never felt she had to steer clear of hostilities. This year, though, she has seen a shift in the way people talk. Her friends’ Facebook feeds seem more hateful toward people who are different from them—likely, she says, because of this election.

In a waiting room the other day, a man looked her up and down, and glared at her. For the first time in years, she wondered if she was being ostracized because of her skin color.

The Majority We’re Not Hearing About

Delicia and Oscar’s experience and the NPR podcast factoid suddenly came together, and I wondered, “What if most Americans really don’t want to deport all Mexicans?”

“What if most of us know someone just like Oscar and Delicia—who work hard, love their kids, pay their taxes—and who struggle with the same things the rest of us do—staying fit, keeping on top of their bills, and making sure their dog doesn’t terrorize the mailman?”

Well, not all of us have a mailman who is a “pansy,” according to Delicia, or a fiercely protective dog, but most of the rest of that applies.

What we don’t share with our undocumented neighbors is their struggle—desperate journeys and relentless, hard work, all to get to the place we’ve taken for granted: the United States.

They know it’s not the Promised Land.

Oscar’s Story

Oscar said he was the only one of his brothers who was interested in coming to the U.S. One of his sisters lived in Texas, and asked if he wanted to come. He had just returned from working two years in a larger city, away from his family, to help with their bills, but he decided to accept her invitation. His sister and her husband paid what he needed to cross the border.

He and a few acquaintances from his hometown, along with a few other people they didn’t know, met their guide in a desert near Chihuahua.

Oscar discovered what many others have—crossing the border is not easy. Getting caught isn’t the only danger; thirst, cold, heat, and exhaustion can be just as bad.

Their guide had not prepared them well: they had on only the clothes they were wearing, and carried only a little food and water. They walked all night: the desert was freezing, and Oscar, who had no jacket, shivered uncontrollably.

The next day, as they walked through the desert near Chihuahua, their water ran out. During the day, they sweated profusely in the heat, and when they had no water for a whole day, some of the ones in the group became sick. They all had little energy. Finally, they came across a home that had a windmill beside it, and they gratefully slaked their thirst.

Once in Texas, though, Oscar’s life was not much easier. He had no steady job; every day, he would go to a designated meeting spot, where other workers would gather. Employers looking for help during the day would come by and pick up as many people as they needed, and then bring them back at night. Oscar remembers doing many kinds of work, including landscaping.

He knew no English when he came, but began picking it up as he listened to people speaking the language. That is still one of the hardest parts of living in the United States, he says—not being able to communicate easily.

He tries, he told me, but the complexities of the language are confusing, and he and Delicia often argue—usually good-naturedly—when she tries to teach him English: over the hundred different meanings of the word, “to,” for example.

Oscar lived in Texas for four years, then got an offer from friends in Hutchinson, Kansas, to work in a roofing business. He started with doing shingles on private residences, and then switched to a company doing commercial jobs.

Oscar moved to Kansas in June or July of 2008, when he was twenty-four. That September, he met Delicia, a single mom supporting her two daughters, Yazmin and Amaya. They began dating and two years later, got married. They have two boys together—Osiyel and Isiye. Oscar takes his step-daughters’ drama with patient good humor, and dotes on his sons.

The kids have started talking to Oscar in Spanish, which he appreciates. At the same time, he is learning English, as his sons have learned to talk. He talks to them in Spanish, and they often answer him in English—which is exactly, Delicia says, what she does with her dad.

Oscar and Delicia feel it’s important that their kids continue to speak Spanish. “It’s good for their brain!” Delicia says, and tells her kids that they need to know it, or they’re not going to be able to communicate with Oscar’s family.

Oscar struggles to adapt to the American language, and Delicia works to help her kids live well in both cultures that permeate their lives—the broader culture, and their heritage Mexican culture.

Oscar and Delicia’s Contribution to Society

I asked Delicia if she feels people have false stereotypes of Mexicans. She told me she often hears complaints that illegal immigrants come here, get on government programs, and don’t pay taxes. She also hears people say they’re lazy, or that they do drugs.

By contrast, she points to her husband. He goes to work at 6:00 in the morning, and gets home after 7:00 at night. He pays taxes: they applied for a tax number for him, and they’ve faithfully paid for the last six years.

They don’t get Earned Income Credit, either, like most families with four children would. They get about half as much back on their tax return as they could if Oscar were a citizen, but pay just as much as anyone else.

Sure, Delicia says, there probably are Mexicans who do drugs or who live off the government. But there are a lot of them who work hard, aren’t into crime, and pay their taxes.

Oscar and Delicia’s Fear

I asked Oscar what is the hardest part about living in the US, adding by way of example, “Not being able to see your family?” He thought about it, and said that is hard; he can’t go back and visit his parents at all until he gets his papers. What is hardest, he said, is not knowing the language.

After a short silence, Delicia said, “I’ll tell you what’s the hardest thing for me. Being afraid he could get sent back at any time.” Several times, she said, Oscar has been stopped, and every time he’s gone to jail for not having a driver’s license.

“They would deport him, then?” I asked.

“Depends who’s working,” Delicia said. “We were really lucky that the judge didn’t send him back. But they are pushing to send people back who commit major crimes like dealing drugs, or abusing kids, not the minor things Oscar’s had.”

They are working on the citizenship process, she said—they got an immigration attorney, who started his application for citizenship. I learned that Oscar falls into the group of immigrants who seek permanent legal status on the basis of marriage to a U.S. citizen. “That should be easy,” Delicia says a lot of people tell her. It’s not.

She told me that after they actually are able to submit his application for legal status, he will have to go back to Mexico and continue the process there. I didn’t know why, until I did more research and found that anyone who has entered and lived in the country illegally has to return to their country of origin and wait a penalty of 3-10 years (depending on how long they lived in the US) to return, working with the immigration office in their country to be approved.

One way to avoid that wait, though, Delicia said, is for her to apply for a hardship status—proving that she needs to have his support with the kids. He could be in Mexico for three months—he could be there as long as ten years. It’s so hard to know how long the process could be, and if he will be approved at all.

Delicia is hopeful, though, that the whole process could take about a year and a half.

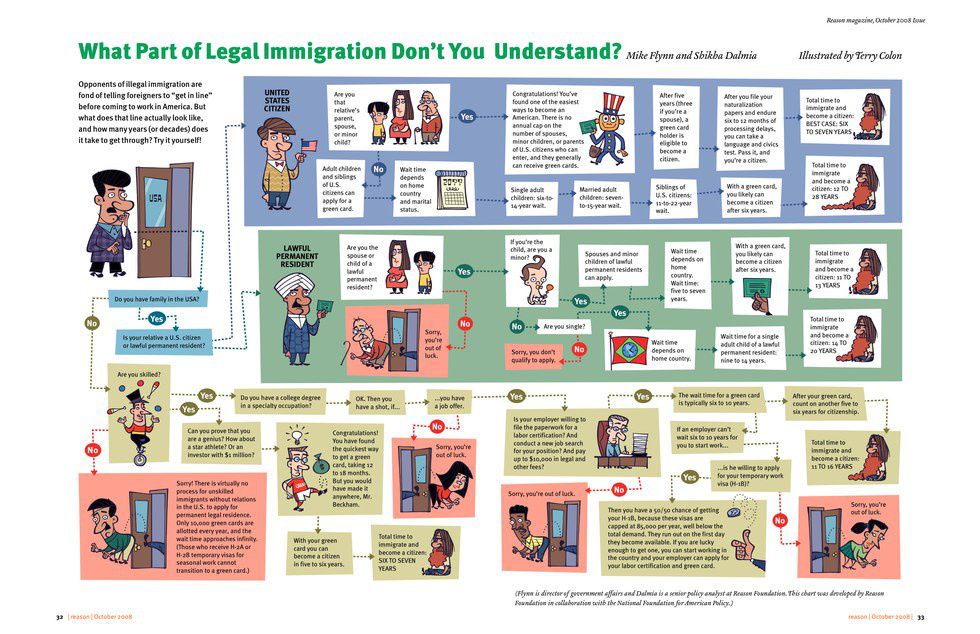

And, by the way, if you're as confused as I am about the process, you might find this article helpful.

4 Paths to Legal Status for Undocumented Immigrants

Here’s a graphic that over-simplifies the process, but also helps. View it full-size here.

What is my point?

I write all this to challenge two stereotypes: that Americans are hostile to immigrants, and that immigrants are lazy and a burden to society.

Yes, I write this based on my personal experience. I learned to know many Mexican families in my hometown when I worked at RISE Kid’s church, and fell in love with their vibrant, close-knit, and occasionally noisy homes.

They reminded me of my own Mennonite culture: they cook, just like we do, except that they’re frying tortillas while we’re mashing potatoes, and they know everything about everyone in their unbelievably-large-blood-related families which make up their communities.

Their houses have neatly tiled floors, many with walls freshly painted with orange or red. The yards are often fenced, sometimes with the kids’ toys spilling all over the grass, right beside the truck their dad is working on.

Rigo, who does home renovation, and contracted with the company I work for, taught me how to spray texture onto walls. He told me about the hours he works—from 6am to at least 8 or 9pm at night.

I'm generalizing here as I describe my friends, but I'm not trying to caricature them. What has impressed me is the way the Mexican parents are often present in their kids’ lives, even though they work long hours, and how their community looks out for each other.

They felt less like a threat, and a lot more like friends.

They seemed less like job-stealers and a lot more like job-creators.

And now, through Oscar’s story, I see just how courageous they have to be to come here—hoping for the same opportunity I take for granted.

Why should we, by the most arbitrary chance of birth, deny them the same right we’ve been given?