When I was 12, I tried to read Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. I grabbed a copy from my sister’s bookshelf, ran up to my room and crawled across 13 pages. Bewildered and dejected, I decided I must not like to read. I put Fyodor on my bookshelf, stuffed between Foxtrot comics and Tom Clancy novels, and there the book sat for 10 years.

I wanted to read Crime and Punishment because my sister had read it, and I wanted to tell people I’d read Dostoevsky too. But, that one attempt at reading those dreary 13 pages minced my drive to read for years. I don’t think my experience is that much different from many other people.

Often, when talking about reading, I hear people, whose names I’ll rest in anonymity, say “I don’t like to read” and “I’m not much of reader.” When I press further, the stock answer is “I tried reading [insert classic work here] in high school but just couldn’t get into it.” I get it. Shakespeare alone has probably committed high school readership genocide—the pacing of the work mangled by necessary translation. To the novice reader, Joyce’s Ulysses, which is ranked number 1 on Modern Library’s top 100 novels list, looks like 756 pages worth of Boggle transcribed. Many classics are hard and a lot of people try to read them because there is a misty pretension hovering over the pages. The idea is that smart people read these books. If you read them, you’re smart too. You should read them. They’re hard? Didn’t finish? You must not like reading.

This is not the case. Because you’ve read Ulysses, does not mean you understood Ulysses. If you understood Ulysses, you probably didn’t understand Ulysses. Challenging works are fine, and there are complex masterpieces to be read, but readers who only focus on archaic classics and press the ejector button when they’re hard to read miss out on millions of miles of in-between space. The Catcher in the Rye and To Kill a Mockingbird are great works because they serve as a step ladder to literature. Short story collections are almost always overlooked by prospective pretentious readers because they’re rarely as famous as an author’s novel. But, short stories are shorter, almost always more readable and serve as perfect introductions to the author’s style and subject matter.

If you’re a reader, read on. If you’re not, read more literature. In the 1000 years Between Beowulf and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, there are, inevitably, thousands of poems, short stories, novels and non-fiction works that a non-reader hasn’t found yet. Find them and devour them. If you find the right work, it’s easy. I promise.

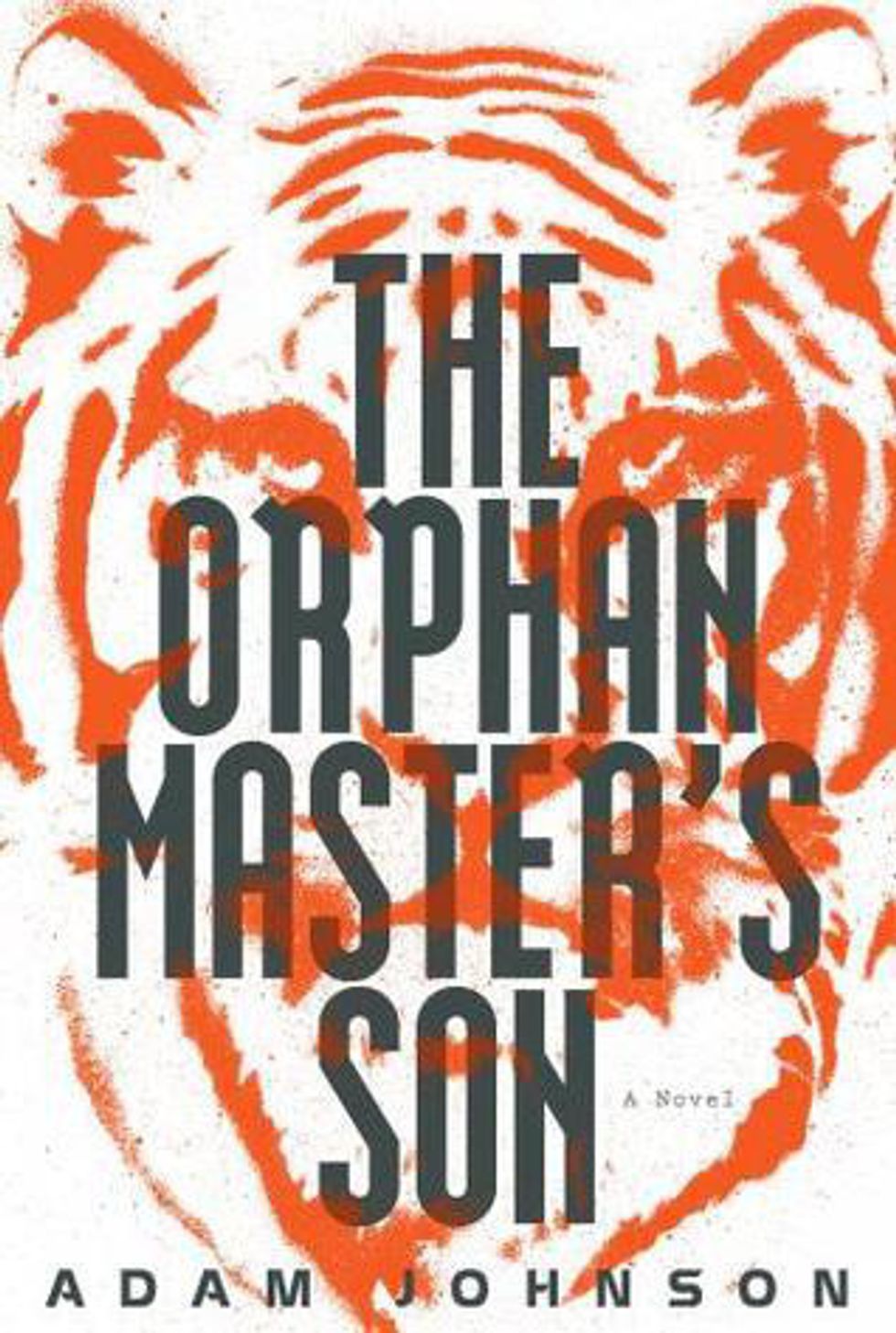

A few months after I dropped out of college, I read Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son. That one work destroyed the idea that I was a non-reader, and, although I wasn’t in school, I tore through more pages than I ever did for class. I haven’t stopped reading since.

I still haven’t read Dostoevsky, but now I’ve read Solzhenitsyn, Faulkner, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Hemingway, Baldwin, Conrad, Coetzee and a lot of other names that would have impressed my twelve-year-old self. I was able to push forward because I stopped reading pretentiously and, instead, read works I understood and enjoyed. Writers are not gods. There are classics that don't hold up. Some great books you’ll connect with; some great books you’ll hate. Stop reading pretentiously and instead find literature you love. Then, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read and read.