Let’s do a little experiment.

Below this paragraph is a work of modern art. Now, without doing any research and without knowing anything else about the work, do a formal analysis this painting. (For those of you who are in the know, pretend that you don’t know anything about the context of modern art.)

Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting (1951)

There’s not really a whole lot to say, is there? These are, for all intents and purposes, three blank canvases hung on the wall and that seems to be about it.

Now, let’s take a look at some critical commentary on Rauschenberg’s work. According to John Milton Cage Jr., "the work is made up of “hypersensitive screens” which react to environmental changes in the room so as to “lead to the possibility of pure experience." The work is a rejection of substance, instead embracing a quasi-postmodern reflexivity. Or, at least, so the art community claims.

Nope, it still just looks like blank canvas.

We have a problem here or, rather, the art community has a problem. Here’s a work of art which has, when explained, rich meaning, but it makes itself impossible for formalistic analysis. There is, quite literally, nothing here to analyze. You can’t talk about the line-work, coloring, or even about a nonrepresentational reflection of the artist (a la Jackson Pollock). There is simply nothing there.

Barnett Newman’s Onement VI (1953).

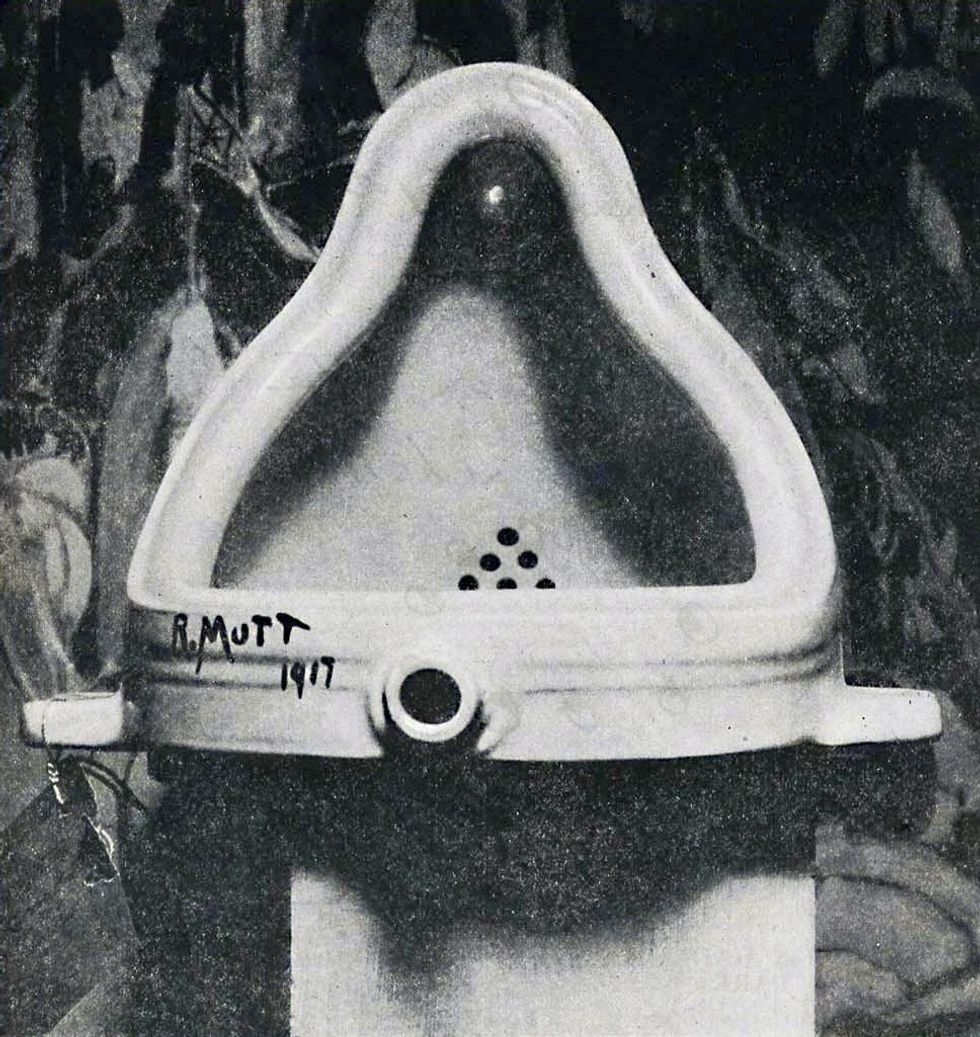

Without formalistic analysis, art must be understood via contextual means. In other words, we have to look at art as it falls within the tradition of art as a whole. “How does this work contribute to the progression of art?” Consider Duchamp’s Fountain, created in 1917.

Yes, before you ask, it is just a urinal.

See, Duchamp was clever. At this point in time, art was still seen as something that had to take a great deal of skill and had to be aesthetically pleasing. With this sculpture Duchamp turned the art world on its head and everyone knew about it. That last part is important, because it’s at the heart of what makes contemporary “modern art” so frustrating.

In any other medium, context is not required to analyze and appreciate a work. Rather, context offers the opportunity for deeper and more critical analysis. So why should visual art be treated differently from its other artistic counterparts?

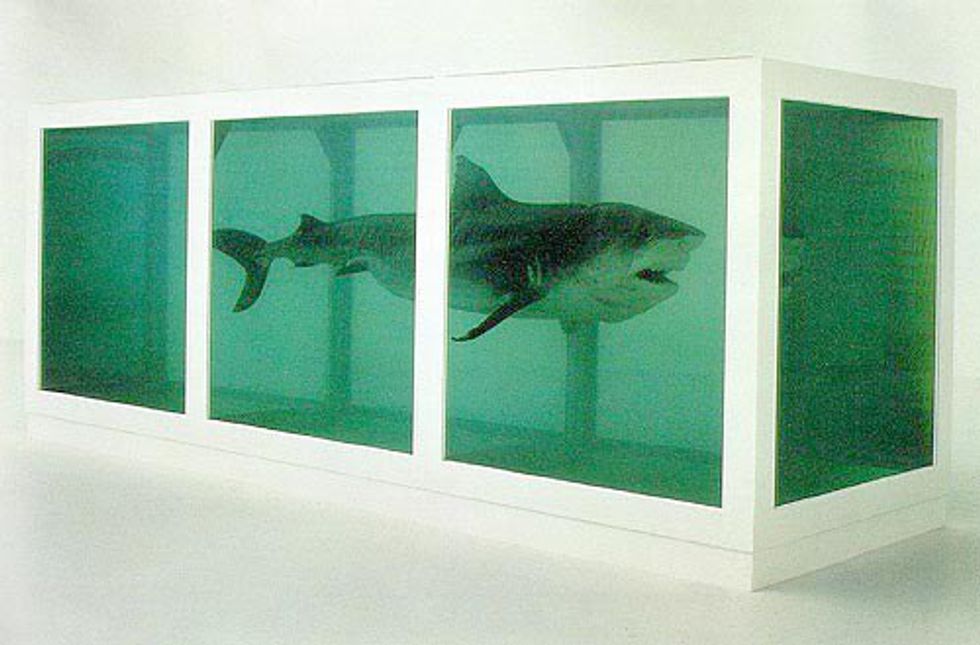

Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991).

My concern isn’t that these works have meaning. In fact, my concern is quite the opposite. My concern is that by pulling on tradition that is outside of public discourse, the modern art community is turning art meaningless. When an intelligent person walks into a museum and says, “I don’t get it,” it represents the failure of discourse between the art community and the outside world.

Visual art is, fundamentally, a communicative medium. Although it is less direct than its literary and cinematic counterparts, visual art retains every bit as much power (and, depending on you ask, quite a bit more) to convey complex emotions, ideas, and concepts. Therefore, when even knowledgeable viewers are unable to find meaning from the content alone or are unable to pull from the incredibly niche knowledge required to appreciate a work, public discourse (and, consequently, modern art) has failed.

Ai Weiwei’s Han Jar Overpainted with Coca-Cola Logo (1995).

Now, that’s not to say that all modern artists are disengaged from public discourse. On a strictly personal level, some of the artists who I find to be the most impressive are wrapped up in public involvement. The Chinese artist and political activist Ai Weiwei is largely reliant upon his mass-media image for his success and, as a result, very little doubt and confusion surrounds his works. Others, like Barbara Krueger, pull less from art culture “in-jokes” and more from popular culture.

But these artists don’t change the overwhelming trend that is members of the art community being out of touch with the rest of the world. The failure of modern art is not one of aesthetic, but of conversation. If people cannot understand art, then the problem is one of engaging the public.

I’m not saying that the art aficionados out there can’t appreciate the occasional urinal or ultra-reflexive blank canvas. I’m just suggesting that perhaps it's time to quit impressing the critics with impressive intertextual allusions and time to start catching the public up on the last century of art and art theory.