Way back when I was a senior in high school, I journeyed to the mystical land of Chicago, Illinois. It was there that I learned about something called minimalist art. I didn’t think I’d take that much of a shine to it, actually: I love me a Van Gogh or a Monet, and the whole point of minimalism is pretty much to rebel against that kind of aesthetic. Wandering around those galleries and museums, though, I found this one sculpture that came to embody everything I believed about the discipline I would dedicate my days and nights to for the next four years:

I know—it’s pretty much the opposite of impressive. In fact, it’s a bit weird looking: the canvas is all splotchy and wrinkled, the sides are kind of wonky, and for something called “Purple Octagonal,” it doesn’t really look all that purple. But here’s the thing: it’s still a shade of purple, even if it’s not what we usually think of when we hear the word “purple.” Even though it looks a bit abnormal, it still fulfills all the requirements to be considered an octagon. And even though it’s made of colored canvas and is mounted on the wall, it isn’t a painting, because, well, it wasn’t painted. Even better: there isn’t a right or wrong way to put it on the wall, because there’s no top or bottom. I have seen this sculpture three times in three different museums, and each time, it was at a different height on the wall and oriented a different way. This sculpture challenges the norms and notions we have about what things are or should be, and it can be interpreted differently by each person who mounts it, looks at it, or talks about it.

“But Alex!” I hear you cry, “this is supposed to be an article about English! Why are you going on about some crappy octagon?” Well, dear reader, because I’m an English major, and this trip happened because I was taking two honors English classes in my senior year of high school.

Given the title of this article, I’m gonna guess this is you right about now:

If I weren’t me and I didn’t know my reasons, I’d probably be confused, too. But as much as I loved reading, writing, and other English-y things throughout my K-through-12 school career, English classes were extremely hit-and-miss, mostly because of my teachers. I’m not going to name any names here, but I had one who was pretty invested in the “every-single-word-in-this-novel-has-a-deeper-meaning” school of thought, and if any student tried to argue otherwise, their grade was less than favorable.

I was, unfortunately, one of those students.

For example, I’m usually in this state of mind when I’m reading something:

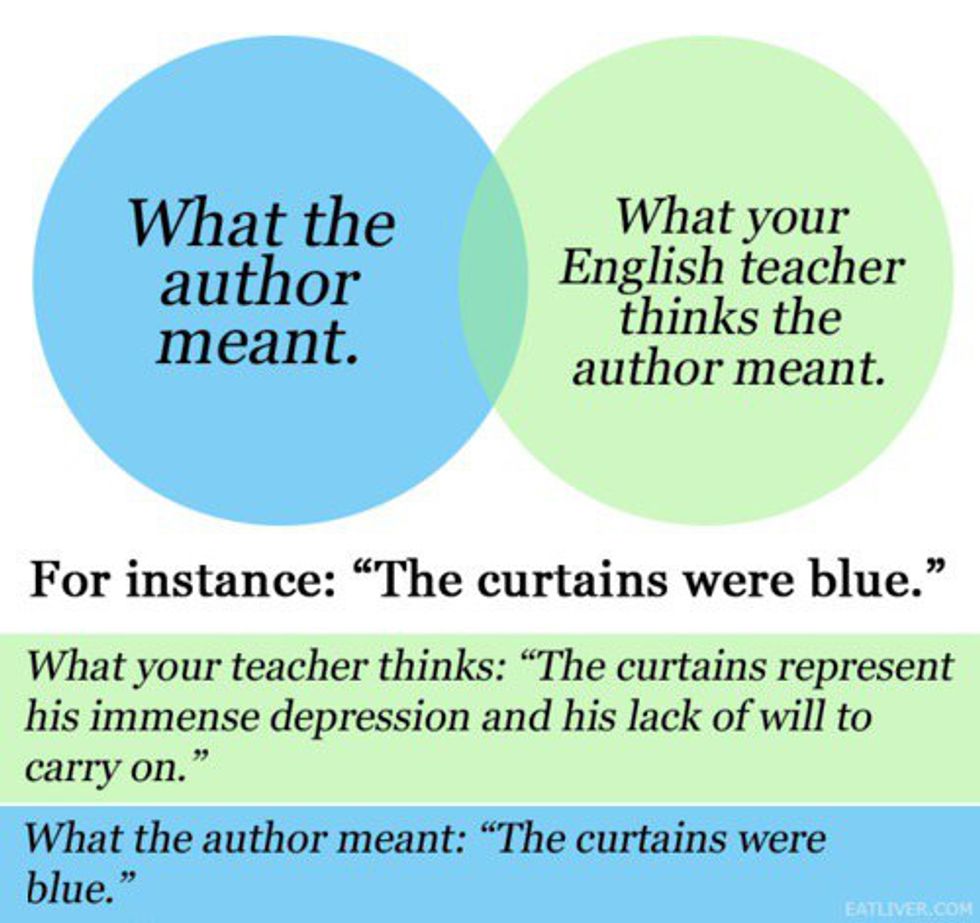

But for this class, I had to start making up all kinds of symbolism nonsense, like “the running water in this scene could represent Character X’s desire to continue living” and other similarly ridiculous statements that I pulled pretty much off the top of my head. Amusingly, simply saying this stuff got me better grades than “Hey, the geographic setting for the story has a lot of water. The author probably knew that, which is probably why this outdoor scene includes water.”

This is not to say that there isn’t a deeper meaning to anything, but I got marked down for not agreeing with my teacher’s interpretations, or for voicing my own thoughts about what the author might have been commenting on by writing what he or she did. I wanted to storm up to this teacher and demand, “Did you go back in time and ask Shakespeare or Dickinson what they meant by that line? No? Then don’t tell me I’m wrong when I have a valid argument.”

I’m not going to say there’s a right or wrong way to teach English, but that was definitely the wrong way.

Some number of years after that class, as I stood in that museum looking at that beautifully bizarre octagon, I smiled to myself and wondered what that teacher would think of it; if the fact that there was no right way to interpret it would make them uncomfortable, or if it would make them reconsider their way of teaching. Really, anyone’s way of looking at Purple Octagonal was a valid way to look at it: maybe one of the sides was the “top” to them, or one of the vertices was. Maybe it was a perfectly valid shade of lilac, or the color was more akin to a healing bruise. That same idea can be applied to just about anything we read in our English classes: with over a dozen critical lenses to evaluate a text through and each reader looking at each word with unique personal experiences, every person’s interpretation of a text is going to be just a little bit different. That’s what makes writing a real art form, just like music or painting, in my opinion, and that’s what makes it so easy for me to hate English class: when the wrong person teaches it, boils it down to black or white, this or that, right or wrong, they take the beauty out of it. Somebody like that would probably look at Purple Octagonal and say that it was sideways or upside-down. Me?

I’d cast them a sideways look and think, “It’s not the art that’s upside-down, my friend.”