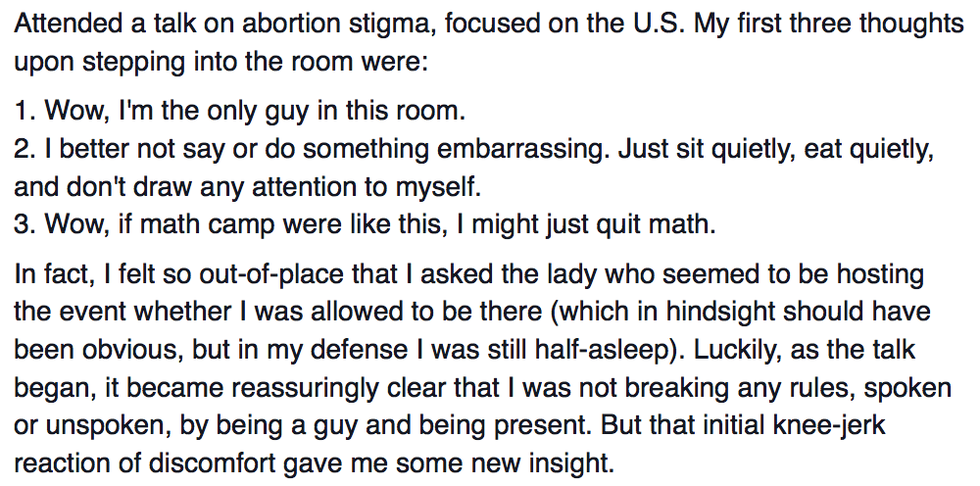

The other day, I stumbled upon an intriguing Facebook post by a friend — it was about his experience walking into a talk on abortion stigma and finding that he was the only man in the room:

His third point touches on an experience shared by many women in STEM: the "only woman in the room" scene, frequently found at math camps or math team practices. There's even a book about it: "Only Woman in the Room."

For me, his post evoked memories of math practices and camps in high school, where I was often the only female in the room. There were usually not more than three girls in my math camp classes or on my team; sometimes I was the only one. The gender balance is better at MIT, though it's still not perfect: I was, for instance, one of two women in a 15-person math class this semester.

I certainly experienced the discomfort that he refers to — it didn't help that I was painfully shy for most of middle and high school, but the shyness was especially pronounced among "math people." Because my gender already drew attention to me, I didn't want to make noise, to make myself conspicuous. My parents asked me why I only became good friends with other girls, of which there were only ever a handful, and I couldn’t justify it: I thought of this as a personal failure. In retrospect, it doesn't seem unusual. Many young teenagers are awkward around the opposite sex; my problem just happened to be amplified by the environment.

When we talk about biases against women in the sciences, we talk about the idea that science is marketed as a game for boys, the idea that women consistently underestimate themselves, the idea that women are viewed negatively when they speak assertively. These are some of the larger systemic shortcomings that underlie the lack of female representation in STEM. But I wonder: Do girls give up on math not only because they underestimate their ability, but also because it just doesn’t feel fun?

Here’s what I mean: say a girl — let's call her Anna — excels in her math class. She moves up to the gifted class. But all the other students are boys, possibly because a good portion of the other girls in her class already believe they're not good at math or because they've accepted that math is for boys: the usual suspects. Then our protagonist, Anna, might have trouble connecting to the other students in the gifted class, even if none of them make fun of her, even if it's never suggested that she doesn't belong there. Kids tend to seek friends of their own gender, after all. She might feel uncomfortable because she likes certain things that are marketed to girls more than boys — maybe she likes to wear dresses — and none of her male classmates do. Then, for reasons completely unrelated to mathematical ability, she begins to dislike that class, and, even though she's a perfectly capable math student, she decides she doesn't think math class is fun and starts to focus on other fields.

So, in this case, no one has treated Anna unfairly, but she gives up on math as a consequence of the absence of other girls in her class. In later years, she might say, "I just wasn't passionate about it." Lack of representation perpetuates itself.

My brother and I were on the same math team; parents hung out in the lobby while the team solved problems. On multiple occasions, after practice ended, my dad would mention that so-and-so’s parents had told him he was lucky to have a daughter who was good at math but also pretty. This made me feel particularly uncomfortable because I was already trying to dress in a way that didn't draw attention to my appearance, and I hadn't come to practice to have my looks evaluated. I struggled to remember a time my brother, or any boy, ever walked into a math competition and was complimented for looking handsome.

I understand that such comments were not meant to be malicious. It’s nice to be called pretty, or cute, and I'd feel much less self-conscious if the same thing happened today. This story does, however, reflect the tendency for women to receive unsolicited comments about their looks, even the most meritocratic and professional of environments.

The problems I've faced have mostly been small, but they pile up and become emotionally taxing. You feel like you're part of the team, but then something happens, and you become aware, once again, that you are the girl on the team.

As far as interactions with other math students go, things were fine most of the time. But there were a few instances when I would think that a male peer appreciated my problem-solving or teaching skills, but I would later find out that he just thought I was cute. It complicated things. There was also a time, at a math camp, when my eight male classmates were sharing scores, and my one female classmate and I were hesitant to show our scores. Eventually, I had my exam face up on the table, and a classmate saw the score, and he was visibly shocked that mine was higher than his, higher than those of many of his friends. "Wow," he said flatly, before turning back around.

I almost never share this story because I'm still worried, to some extent, that I made it up in my head and that I perceived judgment where there was none. I think it's important to be aware, though, that comments that might roll right off the back of someone who feels like they belong might be perceived differently by someone who belongs to an underrepresented demographic. A flat "wow" might sound like "wow, I can't believe you got that score because you don't look like you're good at math," when the intended meaning is, "wow, good job!" To use the phrasing of my Facebook friend, when you feel somewhat like an outsider, it sometimes needs to be made "reassuringly clear" that you do, in fact, belong.

I considered giving up on math competitions many times, and it wasn’t because I was being treated badly or discriminated against. My experience in this regard was quite the opposite: I was treated very fairly and received more than enough recognition for my performance. Nor was the cause a lack of confidence or a belief that STEM wasn't for me. It was subtler, based on feeling—I wanted to quit because I felt disconnected. Outside of math, I didn't think I shared many interests with the community, and I just didn’t think it was worth spending time feeling the way I did. I confused discomfort with the environment for lack of enjoyment for the subject.

The NPR review of "The Only Woman in the Room" puts it this way: "The failure doesn't come from poor grades or explicit rejection, but something more subtle. If science is a boy's club, the door isn't exactly closed in her face—but neither is she ever invited in." The author, Eileen Pollack, studied physics at Yale in the 1970s, and she finds that support for women in STEM has increased in the years since, but "the subtle social forces" are still present.

Had I not been privileged with ample support, I might have bowed out when I was much younger, like our imaginary Anna. I would not be writing from an MIT dorm room today, where algebra, measure theory and topology textbooks decorate my windowsill. In this way, my story stands in contrast to that in "The Only Woman in the Room": my parents are very supportive, and I have always had female role models to look up to; I cannot point to a time when anyone disparaged me or expected less of me as a result of my gender, and no one ever made a special effort to make me feel unwelcome. Many women have not been so lucky.

Eventually, I accepted and embraced the qualities that seemed to separate me from the rest of the team. In a Medium article called "The Making of a Girl Mathlete", Meena Boppana, a Harvard CS student and former female mathlete, describes a similar experience. She remarks, "Puzzle hunts? Chess? Board games? I was never into any of those. And since last I checked, being terrible at Avalon has no bearing on my mathematical ability, I’m OK with that."

I’m older now, and I’ve outgrown much of my self-consciousness. Like Meena, I realized that it was OK to want to do math but also have nonacademic interests that were different from those of the rest of the team. It was a little isolating, but it was no reason to quit or feel bad about myself. Coming to MIT and appreciating its diversity have since broadened my conception of what a "STEM person" or "math person" looks like. But I do wonder — how many other girls have quit math, or STEM, or any male-dominated field, just because they were self-conscious and lonely?

What can we do to help solve the problem? Meena's article (read it!) proposes some solutions, which I will emphasize and outline below. I've talked about girls and women, but under-representation in STEM is a problem that faces other groups as well: racial minorities, nonbinary/trans people and people with disabilities come to mind. So the below applies not only to women but also to other minorities.

1. Get girls (and minorities) to show up.

At MIT, the Undergraduate Society of Women in Mathematics (USWIM) holds an outreach event to encourage young girls to pursue their interest in math. This year, it was a safari-themed math challenge/puzzle hunt for sixth- to seventh-grade girls. Prior to the event, I wondered whether it was a worthwhile endeavor. I wasn't sure if we would make any difference; I didn't think a single day would suddenly make the girls confident about their mathematical abilities. But then we held the event, and some of the girls were clearly enjoying themselves. I wondered if they'd ever participated in math competitions before. And I wondered who was thinking, for the first time, "Hey, this is actually pretty cool."

If we encourage more girls to show up to STEM events, and at each of these events, a few of these girls start to think, "This is something I really like, this is something I want to do on the weekends," then it's worthwhile; these are girls who may eventually become scientists and mathematicians.

To increase participation, the STEM community must increase publicity in groups that are typically underrepresented.

2. Support and encourage other girls (and minorities)!

It is also supremely important that members of underrepresented groups support each other. I think back to my time as a mathlete in high school, and I realize that it was made infinitely better by the encouragement of female friends as well as the support of technical women in my family.

Ideally, minorities would be able to show up to math events and see other people who look like them. Impostor's syndrome would, in that case, be much less of an issue. For women, Math Prize for Girls comes to mind.

If the community does have a clear minority, however, it is especially important that everyone be made to feel welcome. Encouragement and explanations from peers should be easy to come by, especially for those who are more inclined to question their aptitude due to their backgrounds.

In Meena's words:

"...be welcoming to newcomers. The Recurse Center’s “social rules” shows an example of lightweight community norms that one can implement. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve witnessed a conversation along the lines of 'You mean you haven’t HEARD of the Chicken McNugget theorem???' This is silly because everyone has to start somewhere, and not knowing a theorem by name is not at all an indicator of intelligence or potential, it’s an indicator of experience."

3. Collect data.

For instance, Meena has surveyed the Harvard math department. She also refers to Tracy Chou's spreadsheet of gender ratios at tech companies, which quantified the gender gap and "led to accountability and a flurry of conversation".

The Report on the Status of Undergraduate Women at MIT has recently quantified some differences in attitudes toward math classes (see "Section Two: Math Class") between male and female students at MIT—women are more likely to respond "No, too difficult" when asked whether their first math class was at an appropriate level, and less likely to want to take a difficult class again.

I've given a qualitative account of what it's been like for me, but only quantitative evidence will make the argument on a large scale. In the future, I'll probably write a more quantitative and well-researched post, on this subject, so be on the lookout for that!

As children and young adults, we are encouraged to follow our passions, to do what we love. But loving an activity, growing a passion, has to do with more than enjoying the activity at hand; a supportive and encouraging community is often just as important. And when you're the only girl in the room, you might hesitate to keep returning to the room. For the girls, for the women of the future: let's close the gap, grow the passion.