A double-edged sword for stigma

When I was first diagnosed with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), my mother ignored it. Repeating what my doctor had said, I explained to her that many of the issues I faced in school were because of my ADHD. I told her that the symptoms of my disorder makes seemingly easy tasks much more difficult and time-consuming for me.

We had a lot of talks, but at the end of the day, she refused to budge. She told me that I was just lazy and needed to improve my “work ethic”. She reiterated that most of my problems were my own fault, and that I wouldn’t be able to find a husband if I didn’t do well in school.

Some of these statements are familiar to a great many neurodivergent* folks. Clearly my mom isn’t the only parent in the world who messed up when they were forced to confront their child’s mental illness.

Make no mistake: I love my mom. She’s one of the strongest and proudest women I know. But that doesn’t change the fact that my mom is also classist, that she is from a rich family, that she is an older woman raised on cultural values of hard work, that she acts on internalized biases.

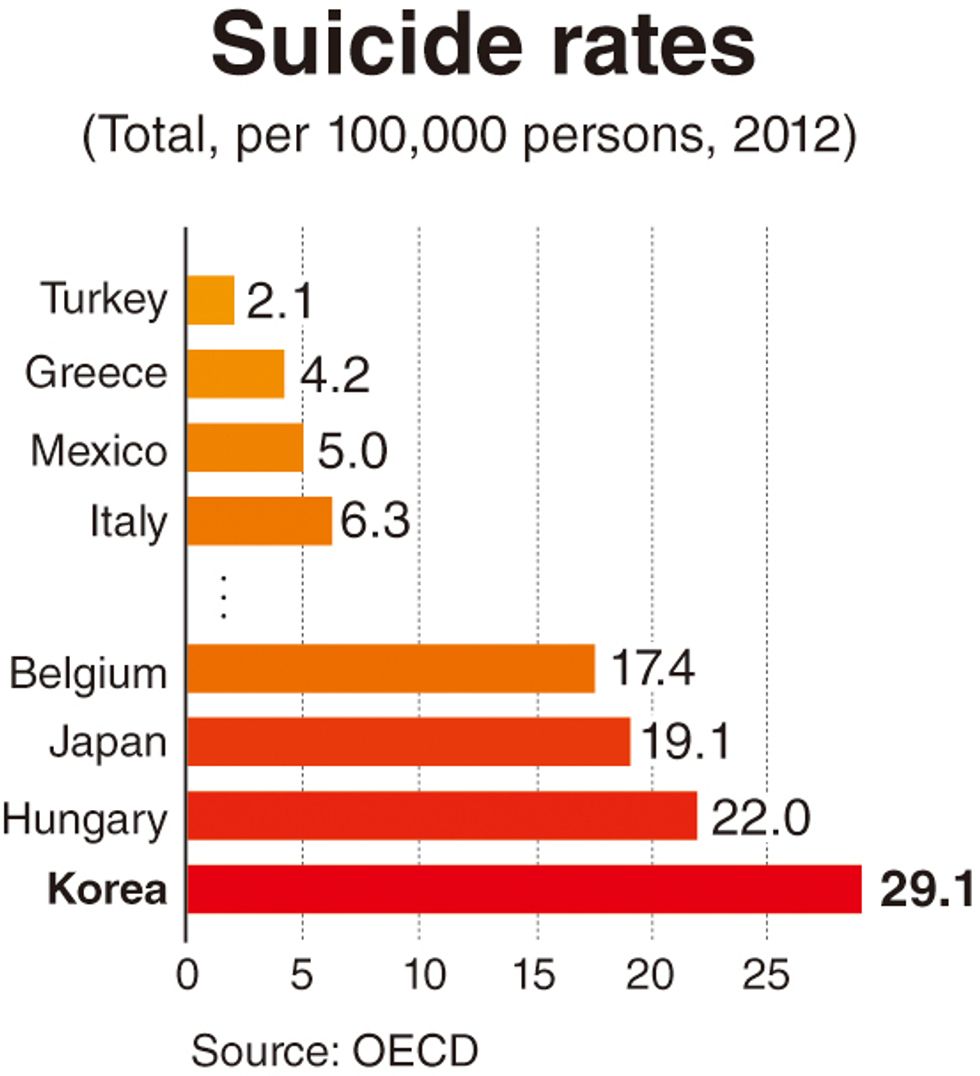

My mom is Korean. This is important because nothing exists in a vacuum. There are no empty voids in our society where we can escape the influence of our cultures and societies, and that includes our ableism. Even though Koreans are not any more or less ableist than Americans, and Korean culture is no more or less accepting of

This is a widespread problem: as of 2006, 90% of psychiatric visits in Korea were involuntary. The suicide rate is one of the highest in the world. The cultural attitudes that cause these numbers are generational, affecting Korean Americans in the United States who then find it hard to seek help from their own families and communities.

These attitudes may not be exclusive to Koreans or East Asians, but the cultural background is. Experiences like these represent neurodivergency. When black neurodivergent people discuss their intersecting experiences of ableism and antiblackness, those experiences represent neurodivergency. When neurodivergent people of color are looking down a double-edged sword, ableism from our own communities along with ableism and racism from society in general, experiences like these need to be uplifted.

Conversations about neurodivergency that operate on the assumption that everyone’s experiences are culturally alike are so often whitewashed conversations. It’s impossible to accurately address stigma against mentally ill and neurodivergent people without also addressing racial stigma that specifically targets neurodivergent people of color.

Prioritizing the right experiences

Racism and ableism are not two different worlds, but rather intersecting regions. Consider the popularly perceived binary: the nonthreatening, vulnerable, and infantilized victims of neurodivergency on one hand, and the “aggressive”, manipulative, untrustworthy, or otherwise “crazy” neurodivergent folks on the other. It may not be easy to admit, but these perceptions often depend on race, gender, sexuality, and other factors.

Suddenly suffering becomes less sympathetic, less relatable, less shocking when it’s on a nonwhite body. Suddenly, images of “harmless” neurodivergent folks become inherently white, while the most violent stereotypes of neurodivergency target black and brown people. Suddenly the sympathetic white neurodivergent faces represent all neurodivergent people.

"Socioeconomic status, in turn, is linked to mental health: People who are impoverished, homeless, incarcerated or have substance abuse problems are at higher risk for poor mental health." -Mental Health America (MHA)

It’s not enough to simply “include” people of color in discussions of ableism and stigma. Why fight for inclusion in a conversation that should have already been ours in the first place? When we ignore the everyday trauma of racial microaggressions and the weight of systemic racism on people’s heads, we ignore a fundamental experience of neurodivergency.

Rather than making race a footnote in discussions of ableism and mental health stigma, it needs to be a reoccurring point.

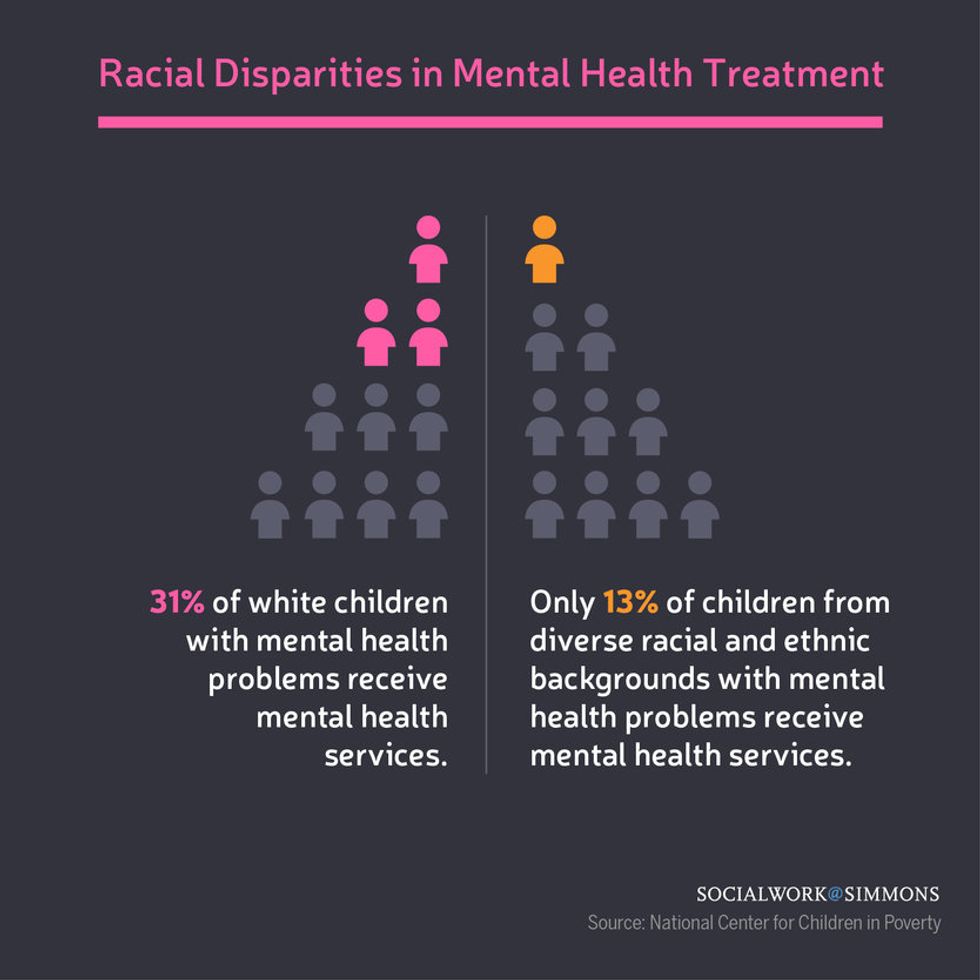

It shouldn’t be necessary to pull out the statistics― the subjectivities and lived experiences of people of color are more than enough. But it never hurts to know:

“African Americans are 20% more likely to experience serious mental health problems than the general population,” reports the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). One of the biggest issues is suicide, which has extremely high rates among black men. Another is PTSD, “because African Americans are more likely to be victims of violent crime.”

In addition, NAMI reports that “only about one-quarter of African Americans seek mental health care, compared to 40% of whites”. Socioeconomic factors, such as lack of access to healthcare, as well as cultural/social barriers are listed as contributing reasons.

Weaponizing identities

Growing acceptance of neurodivergency and neurodivergent individuals isn’t progressive if it’s limited to white neurodivergent folks. In fact, it’s the opposite--any movement that only empowers whites, regardless of their marginalized status, is a movement that upholds white supremacy. Starting from the top and going down doesn’t work. When the most marginalized of our communities are fed, clothed, housed, educated, and cared for, so will everyone else.

This isn’t just baseless theorizing, either. What actually happens when we center white experiences in conversations about mental health?

One example of a recent effect is a trend of whites in “radical” or activist spaces trying to avoid accountability for racist behavior by using their neurodivergent identities. Though this seems like a new development, it turns out to be pretty old. Who hasn’t heard of someone trying to get out of taking responsibility for their behavior by fishing for sympathy?

This is especially insidious for white neurodivergent people because sympathy is so easily within their access. Taking on the victim’s role becomes almost natural. Fragility is so often reserved only for the white and white-passing (and sometimes for light-skinned people of color as well). But this fragility is an illusion: there is absolutely nothing fragile or helpless in intentionally weaponizing your identities to gaslight people of color.

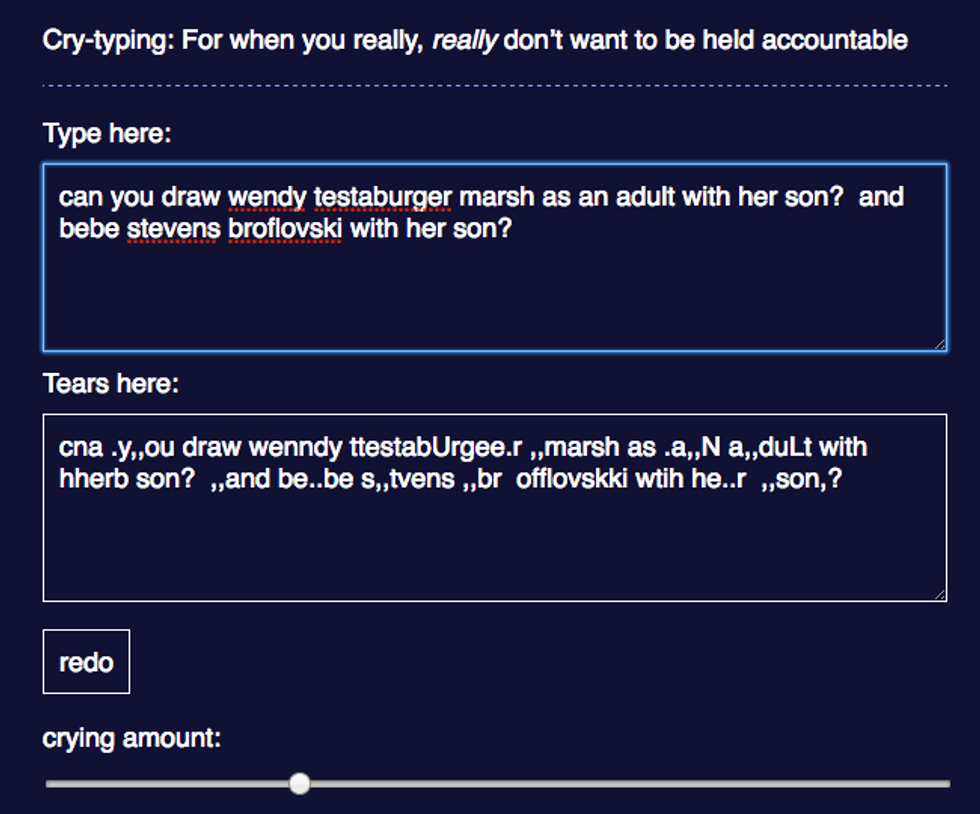

When this is allowed to occur, pointing out someone’s behavior as racist, predatory, or otherwise problematic suddenly becomes “ableist” and therefore invalid. Suddenly it becomes acceptable to respond to criticism by portraying people of color (even other neurodivergent people of color) as aggressors while taking a victim role. Suddenly, we have young, white, self-appointed authorities on social justice going so far as to suicide bait and fake panic/anxiety attack symptoms (like "crytyping") to elicit sympathy. All of this effort just to avoid accountability.

It’s an all too common defense tactic to pin racist or ethnocentric behavior on mental illness. All white people (neurotypicals* included) are capable of perpetuating racism. It follows that being neurodivergent is not a prerequisite for being racist. Racism is abusive behavior, and abuse is never an inherent symptom of mental illness. Mentally ill people are not predisposed to being abusers. The very suggestion plays into some of the most common ableist stereotypes of mentally ill people, especially those with personality disorders.

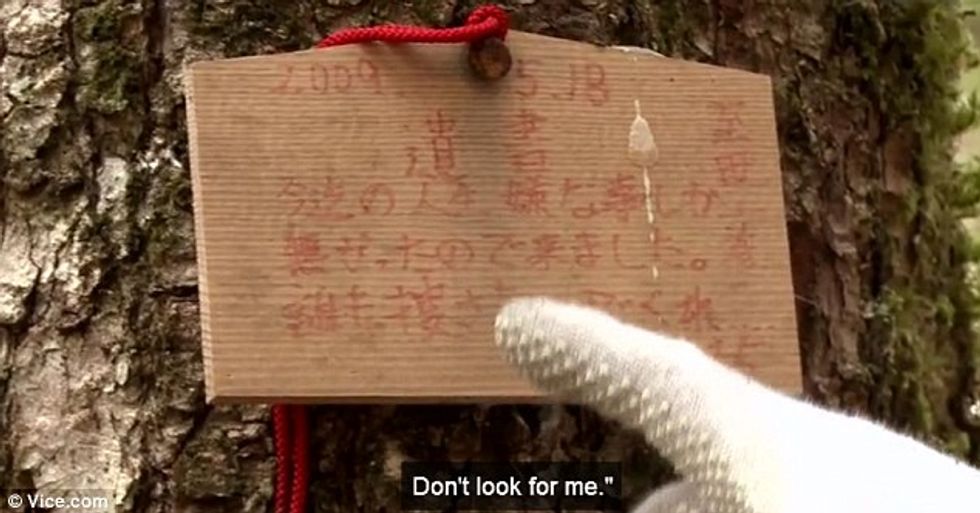

Another example of what happens when we center whiteness in discussions of mental illness: The Forest. The story of Aokigahara, the “Suicide Forest”, is a story that should have been about the lack of resources for mentally ill people and the suicide epidemic in Japan. Instead, it was repackaged and marketed as a horror movie with an all-white cast.

Of course, westernizing Asian stories and replacing the characters with white celebrity faces is nothing new for Hollywood. But “The Forest” reads blatantly as exploitation. Aokigahara is a real place that attracts real suicidal people.

It doesn't even need to be said that if the second most popular suicide site in the world only attracted western white people, no one would even think to turn it into entertainment.

What you see when you think of neurodivergency

There’s no getting around the fact that every single one of us has internalized similar images of neurodivergency. From the stoic, silent Asians of Hollywood to the even more violent stereotypes of black and brown masculinity in the media, our image of emotional vulnerability completely excludes people of color.

Time and time again, these so-called “positive” stereotypes paint people of color as inherently less emotional, mentally stronger, or somehow invincible to pain and suffering. These stereotypes are not only dehumanizing, but they completely erase the actual struggles that communities of color face.

Changing the way we talk about neurodivergency starts with changing the images we see in neurodivergency. This means paying attention to the different ways our communities face ableism. This means centering neurodivergent people of color. Neurodivergent poor people. Neurodivergent LGBT people. Neurodivergent women of color. Neurodivergent trans people (especially trans women of color, who experience higher rates of suicide, harassment, and violence).

Most of all, however, it means being uncomfortable. Addressing your own privileges is not meant to be an easy process—but it’s an obligatory one for all of us, especially when the goal is collective liberation.

*Vocab

Neurodivergent ― "having a brain that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of “normal.”"

Neurotypical ― "having a style of neurocognitive functioning that falls within the dominant societal standards of “normal.”"

Neurodiversity ― "the diversity of human brains and minds – the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species."