When grandpa died, I wasn’t there. I went to visit him just days before he passed away. The best way I can describe that experience is in this exercise from a Stanford writing class I took this past summer:

“I stepped into the hospice, uncertain of what to expect. I had walked into many nursing homes in the past when I worked for a clothing company that specialized in clothing for the less able, but it was never a personal visit. The receptionist pointed me in the right direction and let me proceed alone, offering neither oversight nor comfort. There was no need to protect the already dying.

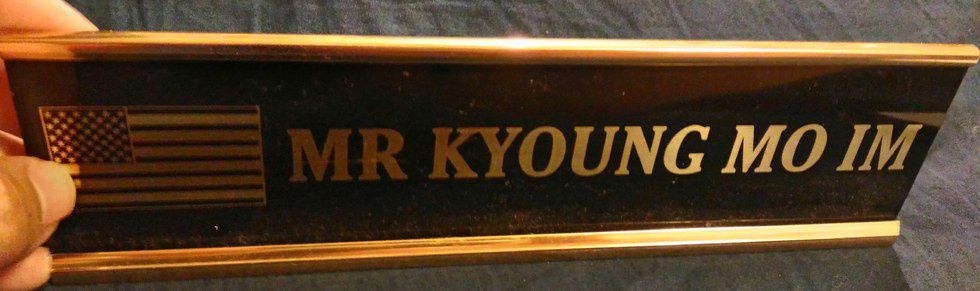

I slowly edged along remembering the phone call two weeks prior. Grandpa had called me again, this time, to tell me he was dying. He, unlike the calls before this, said to please worry, to please visit, to please tell my father to come, to please see him one last time. He sounded like grandpa, like the same grandpa I had seen 9 years ago, but not like the grandpa he had taught me to know. The grandpa that was strong and taller than me. I read carefully the signs by the door. I step in and come out again to inspect the black name plaques. They have one name on the other printed in white square letters, both with surnames “Im.” I realize I don’t know my grandparents’ names. I walk around the hall, double checking that these two are the only Asian elderly. These unrecognizable two. I thought my grandmother had died already, but she was here hooked to life support. A survivor of negligent care. She choked on food is what my aunt later told me. My grandfather was so small. Like a child or a war victim that had finally succumbed to the horrors after nearly 5 decades.

“Grandpa” I touched him gently, fearful he might break, even more, fearful he might not wake up.

When my aunt arrived she yelled at the nursing staff for letting her father suffocate. “He needs this oxygen. Why aren’t you giving him the oxygen?” The cancer was eating his lungs, breathing felt like drowning, the tubes on his face were spider webs that he had to rip away, the people in the room were just shadows, strangers, tokens of luck to hold onto til next time.

I held his hand. It was cold and wrinkled and unresponsive. Two weeks ago he could speak full sentences. One week ago I didn’t have the funds to fly sooner. Today I didn’t know who this man was and the guilt of never learning Korean burned the pit of my stomach as his hand and mine turned our cold bond lukewarm.“

I volunteered to read it because I felt it really captured the essence of the writing task: to write of a haunting place or experience. My hands were shaking and my voice faltered as I read. I reached deep down and that moment was what came out with all my insecurities and fears and disappointments. But there is a flip side to this story. I didn’t just go to see my grandfather die. I went to see how he had lived.

When grandpa died, I went to see his home. I walked into a small, one-bedroom apartment that he had lovingly shared with my grandma. I thumbed through artwork and pictures, found a little booklet where he wrote our names and birthdays, saw small trinkets and toys, and drifted into stories my aunt recited as we searched through trying to make sure we managed to save something meaningful when the government came to clear out the life left in this low-income apartment. I cried at the hospice when I understood that my grandpa was suffering every second. He kept on saying “appo” (“it hurts” in Korean) as tears leaked involuntarily down his face. I cried when my aunt told me how proud my grandfather was that I had finished college, that it was his dream that his grandchildren would. I cried when I saw my aunt cry, she had known him her whole life. I had only known my grandparents since I was 10, when I was abruptly introduced to snow and Christianity upon arriving to Tacoma, Washington. There was always a layer of hesitation and deference. People I was supposed to know but I didn’t know how to talk to. Our relationships were vastly different, my aunt’s with her father, and mine with my grandfather. However, I could not help but imagine being in her shoes. My father, a chronic smoker, also laying there succumbing to the same ailment: lung cancer. Feeling helpless. And my uncle was there, smoking as soon as we stepped outside the hospice. I hate cigarettes more than nearly anything. I refuse to date men who smoke. I was baffled that my uncle could smoke in the face of death.

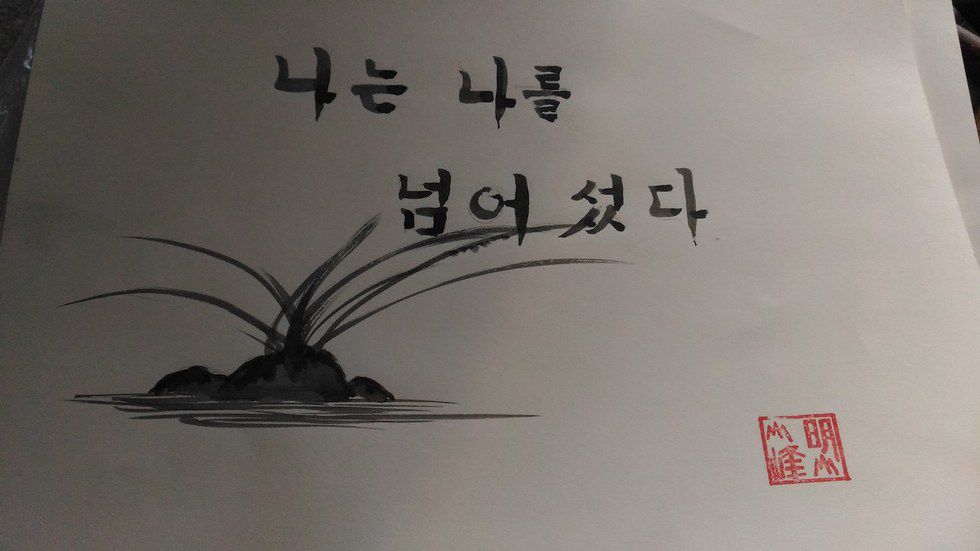

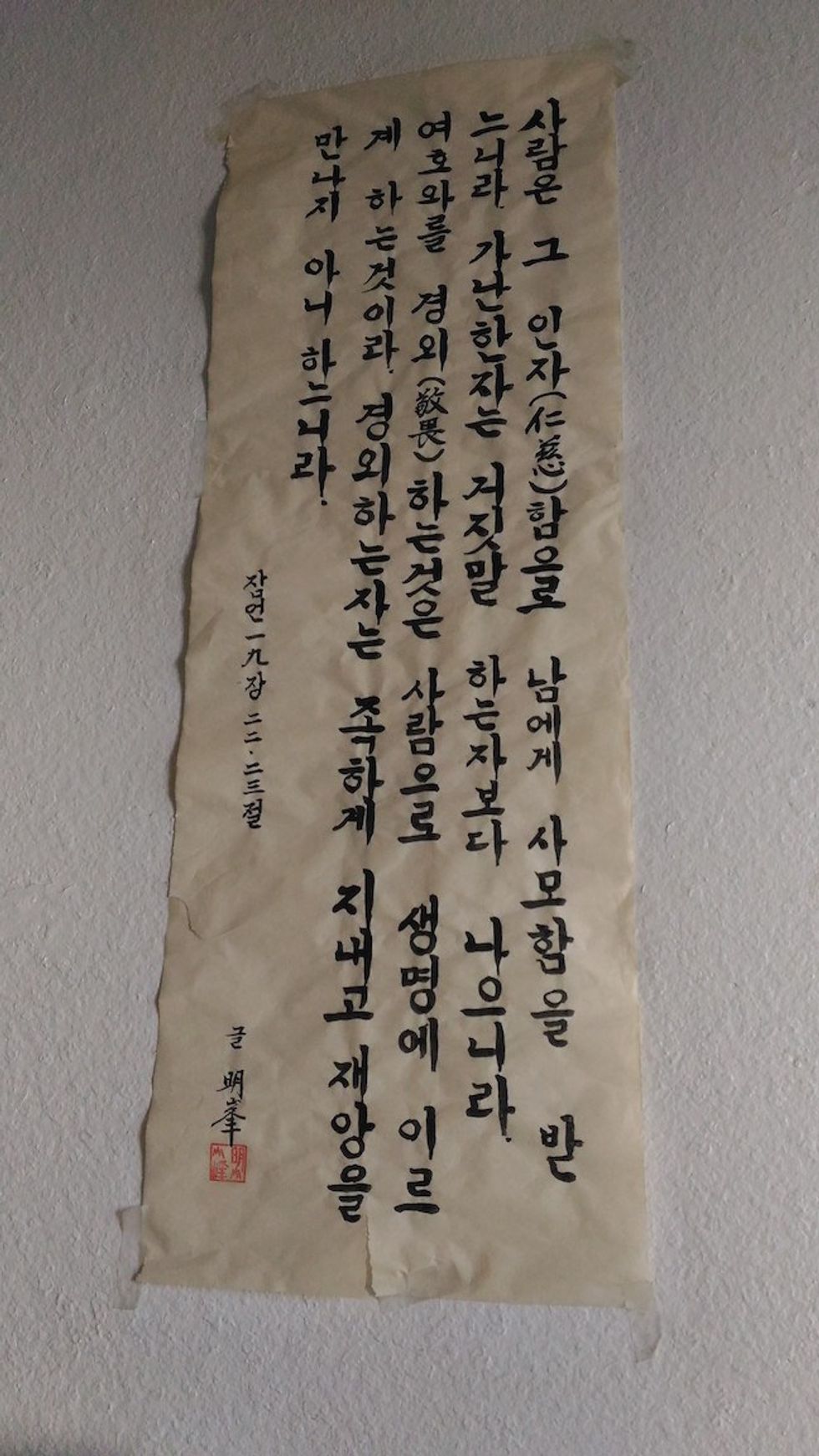

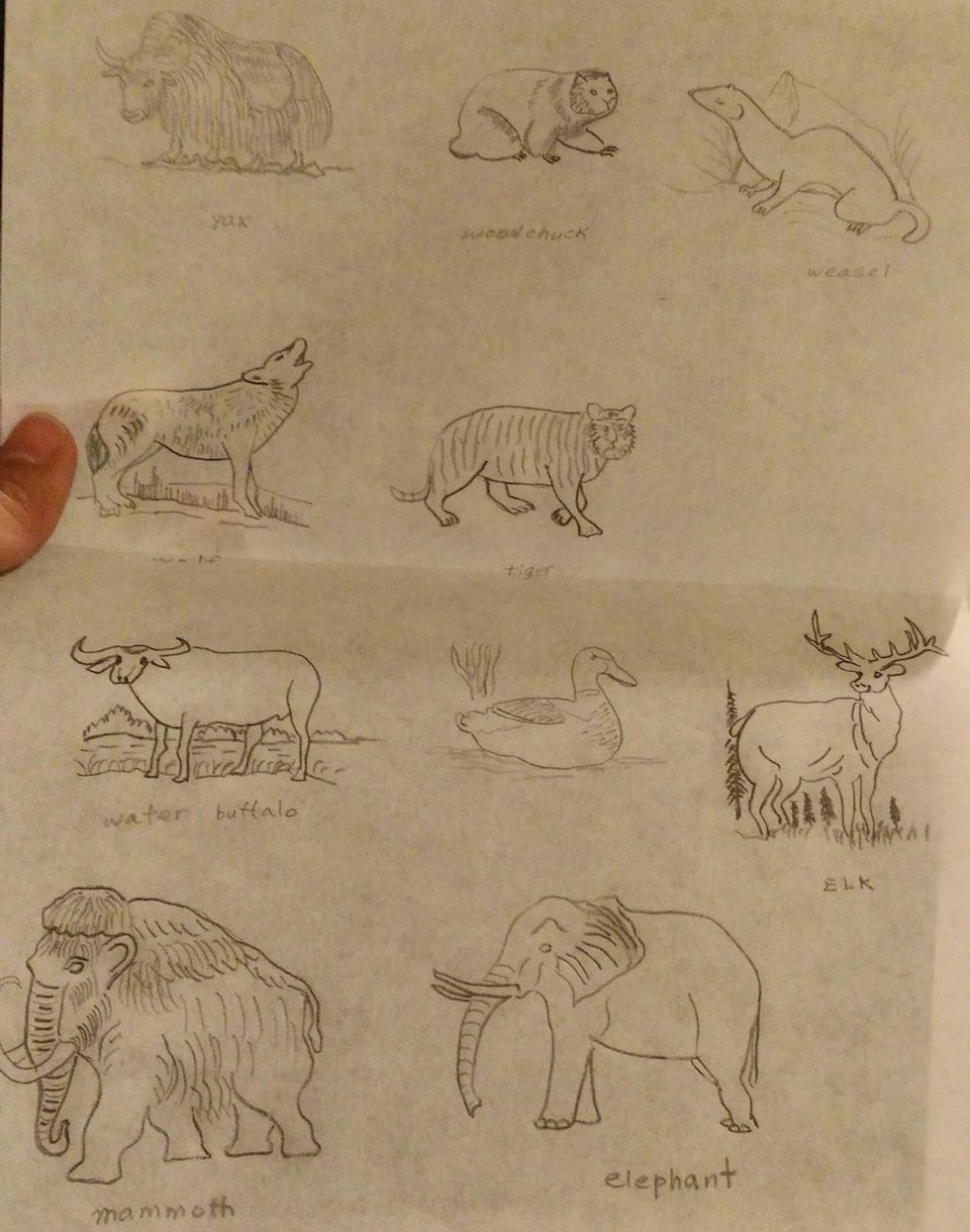

Some of the treasures we found in the lovely apartment were: traditional clothes (“hanbok”), calligraphy materials,

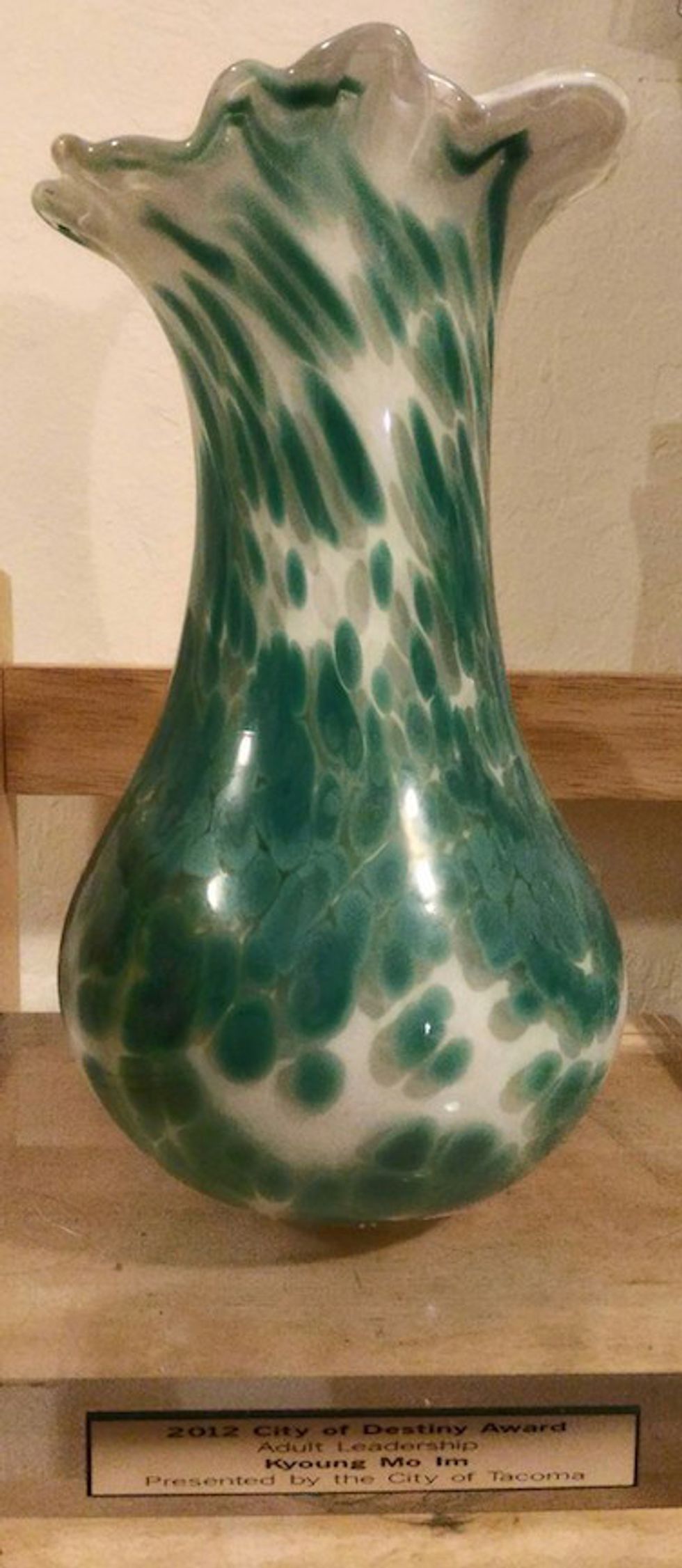

pictures my grandfather had taken, awards he received for his service to the community, his calligraphy art,

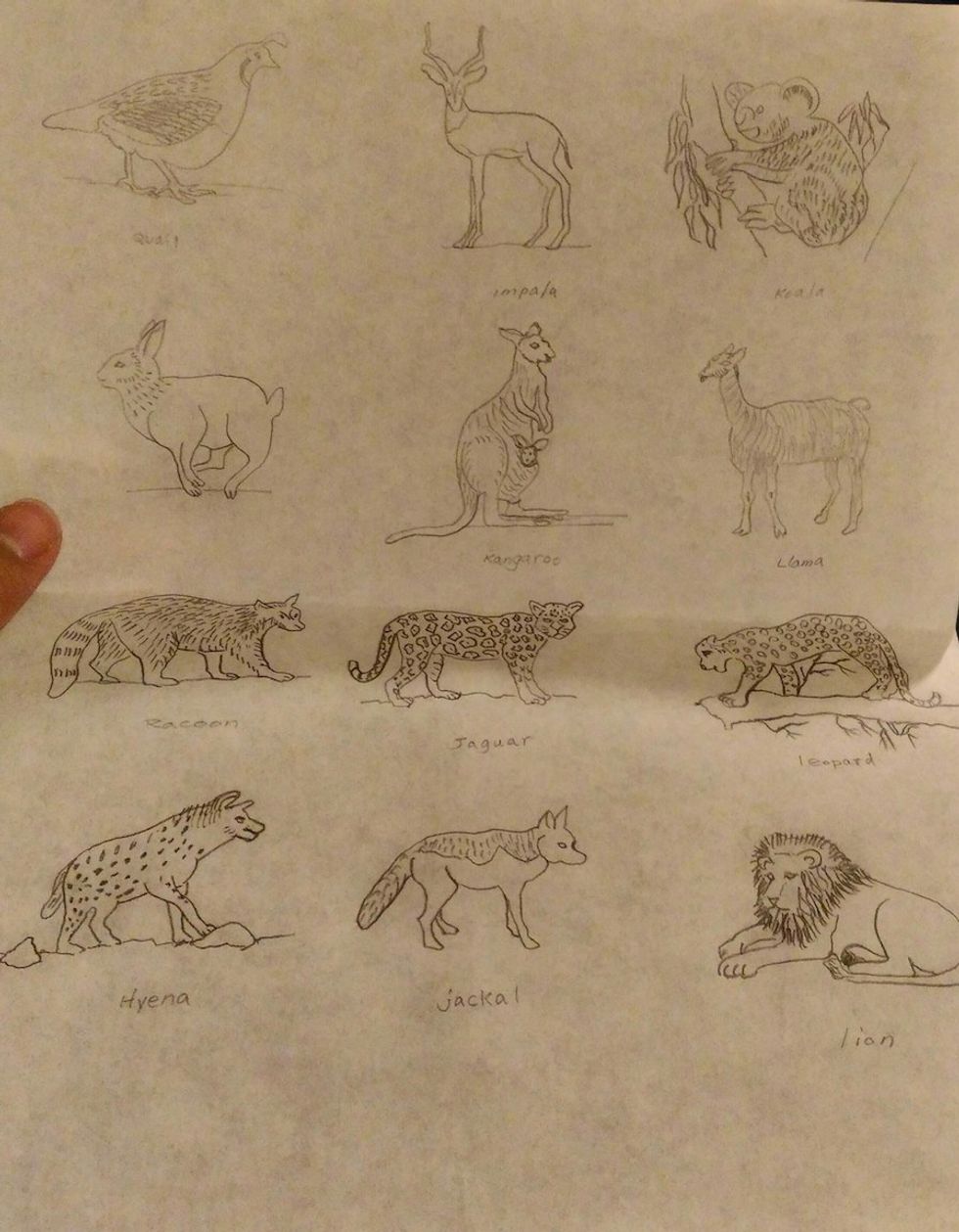

the drawings he made for school children, and a love for lighthouses.

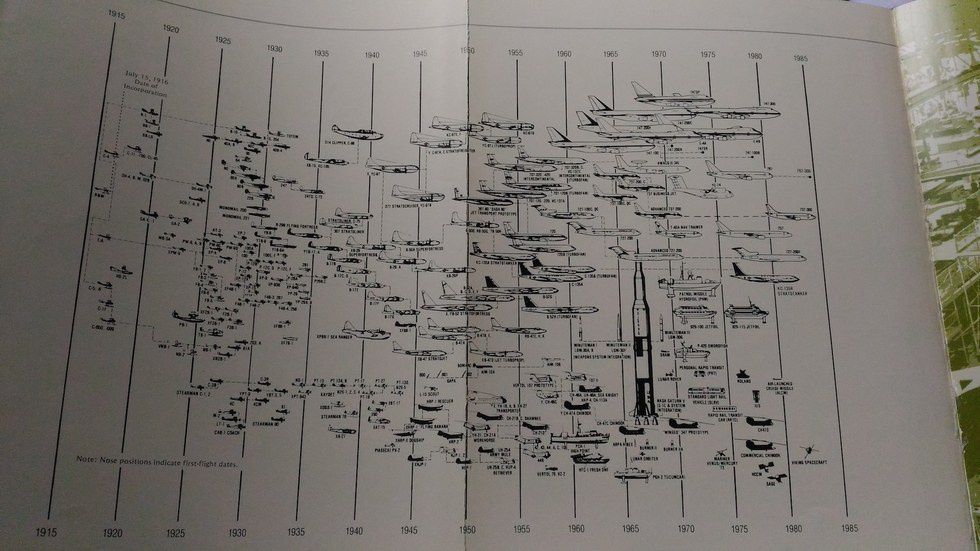

When grandpa died, I discovered how much he lived. My grandpa was an airplane mechanic, in Korea, then somewhere in the Middle East, then in Argentina, and then in the United States.

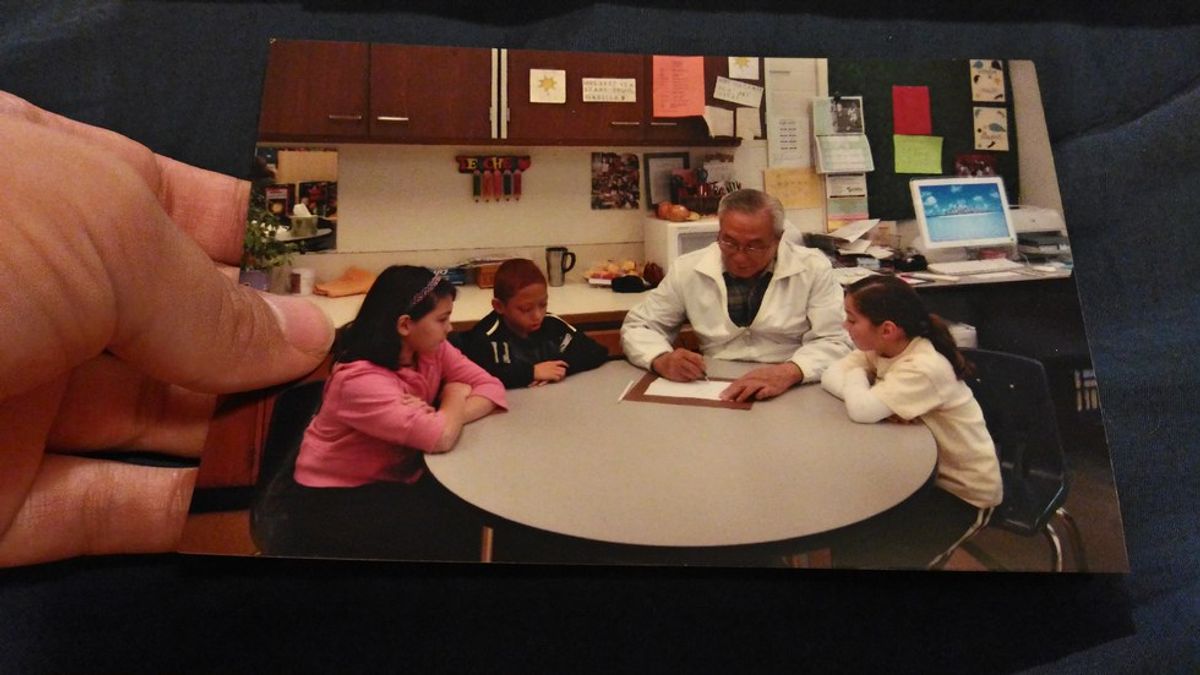

I may or may not have missed some regions, but he was a worldly man who knew where he was going and what it would take to get there. When he retired he became an assistant teacher and also the caretaker of my grandma who had suffered a stroke. He was an amazing teacher. He would draw animals and plants and all sort of objects for his students. Everyone loved him. My aunt told me how, years later, an old student of his recognized him in the street and came over to greet him, but my grandpa was confused at this large man shaking his hand and praising him. Children grow fast. I found pictures of my grandfather surrounded by schoolchildren. I found his awards.

I found his drawings.

I found his books, books that were for learning so that he could keep teaching. My grandpa and I were more alike than I could have ever imagined. And it breaks my heart that I had to find this out through anecdotal evidence and objects. He loved art and writing. He loved building people up. He loved love. His nurse came up to me and told me that it was an honor watching my grandpa visit my grandma every day until he himself had become bed-ridden. The nurse said that they truly loved each other. He loved lighthouses. It’s the symbolism, of shining a light and rising above and being a beacon. One of my favorite phrases is ‘fiat lux’/“let there be light” because to me that means spread knowledge and good. We shared philosophies so deeply entrenched in our DNA.

I’m the type of person who says “I love you” very easily. I love people, I really do. But I’m also the type of person who has trouble acknowledging that I am loved back. Anxiety makes me question this. But I know my grandpa loved me, because he called me a few weeks before he passed away and he wasn’t afraid to share his vulnerability with me, “I’m dying, please come see me.” My grandpa knew how to love and he wanted to see me in his last moments, a time reserved for the most important people in his life. I love my grandpa. And what I love the most about him, is not that he did this or that or that he had interesting things, but that he’s still here. He’s in the hearts of the now-grown children he taught. He’s in the hearts of a family he led through so many countries. He’s in my spirit. He has inspired me to pursue my legacy, to leave so much behind that any regular ‘ol Joe or ordinary Jane can piece the bits together and say “Ah ha! I know exactly who this person was.” And he or she will deduce, through amateur forensic reasoning, that I was honest and good.

What is your legacy in the making?

Part of my legacy can be found in my poetry (https://goo.gl/yTviCn), in my songs (https://goo.gl/ZswqH7), in my site (LearnbyMap.com) and in my newest project: the OneShot podcast (https://goo.gl/fVqOmY)

BONUS: The ultimate homepage for your favorite browser!