I've always wanted to compete on the reality show Master Chef and cook for Gordon Ramsey. Combined with my friends' earnest encouragement, amateur home cooking skills, and competitive drive, I felt like this could be my calling.

But there's one thing that has always prevented me from auditioning. The chef's unique flavors are often inspired by their ethnic origins. In Season 3, the winner Christine Hà incorporated Vietnamese flavors, Luca Manfé from Season 4 specialized in Italian food, and Season 1 winner Whitney Miller brought southern style cooking. My problem is that I don't know what signature flavors I could use to make my dishes my own, when the largest influence in my cooking style comes from Pinterest boards.

On a deeper level I feel guilty that as a Korean; I can't confidently incorporate Korean flavors like one of the chefs who grew up taught by generations of family members. I tried assuring myself that I could study Korean cooking flavors and techniques; and while that is true, I'm lacking the familial connection. Instead of an elderly Korean grandmother teaching me how to pickle kimchi or marinade bulgogi, I grew up with a rice cooker from William and Sonoma.

I've grown up with a lot of contradictions and confusion surrounding my identity and how I express it. In fact, I remember my first identity crisis.

I was in the 4th grade and it was "around the world day" at school. At 10-years-old, I remember feeling torn between what part of my family I would represent because my dad is Irish, my mom is Italian, and I'm also Korean. There were already multiple kids claiming Ireland and Italy, so I thought, I'm going to stand out and do Korea as the only Asian in my class. So, my mom drove me an hour to the closest Korean food store where I picked out a few snacks based on the pictures on the bags. The night before the celebration I got ready and organized all the snacks on a platter.

But the morning of, I told my mom I didn't want to go to school. I was anxious.

What if the students asked me what the snack was called in Korean? What if the next time I pointed out my mom they won't believe me because she's white? Or what if they call me a liar when I tell them I make homemade Italian cookies every Christmas with my Nana and Papa?

For an elementary school kid, these were the most pressing questions holding me back from sharing parts of my identity that I had never truly explored.

So, I stayed home. My mom took off work, and my teacher was left with no idea how to console or understand the deep emotions of young Elisabeth.

The next day I went to class and everything was normal, and I went back to playing with my friends. But I never shared this bizarre experience with anyone in my class because no one else was adopted, and I didn't think they would understand what it's like to feel isolated for not looking like your parents.

Adoption is not a common topic of conversation even among those who are adopted. As a result, I've noticed a societal habit of avoiding conversation about cross-cultural adoptions, as if the topic was something to avoid when really, it's an important part of my identity. So, I've decided to start a dialogue about adoption so that hopefully other individuals who are adopted can relate and people who aren't adopted can learn more about our experience. The following is just one perspective and does not apply to all adoptees, however I'm hoping to shed light on a complicated subject and bring light to an under represented population of people.

Tips for Talking to People Who Are Adopted:

"Today, when I'm asked, I often say that I no longer consider adoption—individual adoptions, or adoption as a practice—in terms of right or wrong. I urge people to go into it with their eyes open, recognizing how complex it truly is; I encourage adopted people to tell their stories, our stories, and let no one else define these experiences for us." -Nicole Chung

1. My life is not a 'Hallmark movie'.

My life is not a tragedy turned happy-go-lucky, and by no means was I "saved" by my adoptive family. Instead, my life began with the loss of my birth family, identity, and culture and this early-life loss has always stayed with me.

Even though I've always known that I'm adopted because my mom and dad are both white, this does not mean that I have always been searching for my birth family. Most people assume if you're adopted that you have this strong urge to find your birth family, and while this may be true for some adoptees, it's not true for all. I caution you when asking people who are adopted, "Do you know your birth family?", because this bold question can evoke a mix of emotions. Whether it be sadness, anger, or embarrassment, it can be uncomfortable answering that question especially because most adoptees have a similar answer- "No, I don't". It's also not the best feeling having others remind me of this lost part of my identity.

2. Avoid saying, "Oh you're adopted? That makes so much sense"

What does that mean? Is there some adoption stereotype I missed? Or are you referring to me as whitewashed and "not like the other Asians"? My friends have told me, "Suds, you're basically white". "You're a twinkie, yellow on the outside white on the inside". "You're a banana". As if these were compliments. What part of my existence screams, "I WISH I WAS WHITE!" ?

This language, whether intentional or not, is harmful to the person you're addressing. Adoption is already a complicated layer, and other people questioning the validity of one's identity only makes it worse.

Because I am happy to inform you, one thing I know is that I don't want to be white.

I personally never envied blonde hair, colored eyes, or pale skin. (Okay for a brief time I wanted freckles but those are not inherently white). It's rather insulting because I want to be seen as me, I know that I am enough, and for others to question whether I am sends me spiraling back to middle school when I never felt enough. Whether it was I'm not Korean enough because I don't speak the language and can't cook Korean food, or whether I'm not white enough although I was raised by a white family, I am still Asian.

There is no part of my identity that makes "more sense"or "less sense". I simply have many different parts.

3. Don't Behave Like Cashiers

It's very common for cashiers at restaurants and stores to assume my mom and I are not together and ring us up separately. I'd like to say it's because I come off as mature, but I'm sure it's more because we look very different. What would a middle-aged white woman and an Asian teenager possible have in common? I let it roll of my back because I know they aren't trying to be rude (that, and I will probably never see them again).

Similarly, I don't find it offensive when people ask me, "Oh, are you adopted?" upon seeing my mom and I together or a family photo. It's a question evoked by genuine curiosity and an important detail in my life. However, I do take offense when people ask, "Wait, that's you mom? Really? How?" Imagine if the roles were reversed and people questioned if your parents were your real parents. Acting as if somehow,they know more about you and your history than yourself. Pretty shitty. So please, when learning about people's family backgrounds have an open mind, speak with kind intention, and don't assume anything, because every family is different.

4. Whatever you do, don't ask, "So, your birth mom just didn't want you?"

Believe it or not I have been asked this many times, and I always try my best to respond maturely because this is simply an ignorant question that stems from not knowing anything about adoption except what Hollywood movies portray.

There are endless reasons for someone to give a child up for adoption and, each story is unique. For example, some mothers are young and cannot afford to take care of a child, some moms don't have the support of family and friends to help them make the decision let alone raise a child. You may be wondering, why not ask the dad for support? Well, there's the instance of rape or for other reasons the mom is unable to contact the father. In terms of international adoptions, there is also the added complexity of cultural norms and stigmas. For example, in South Korea, it's still considered taboo and not kindly received if women have children out of wedlock.

That being said, not all adoptions can be traced because some children are found outside of police stations, hospitals, parks, or orphanages. Giving a child up for adoption is an extremely brave and difficult choice to make and to assume a mother simply "didn't want" their child is a painful idea to even suggest, and rarely the case.

5. "Giving birth does not make her a mother. Placing a child for adoption does not make her less of one."

I become silently frustrated when people talking about my mom try and make the distinction between my "adoptive mom" and my "real mom". Having two moms is not a matter of choosing which one is my "real mom". My mom is the one who raised me and loves me. For me, there is no question about which mom I'm talking about.

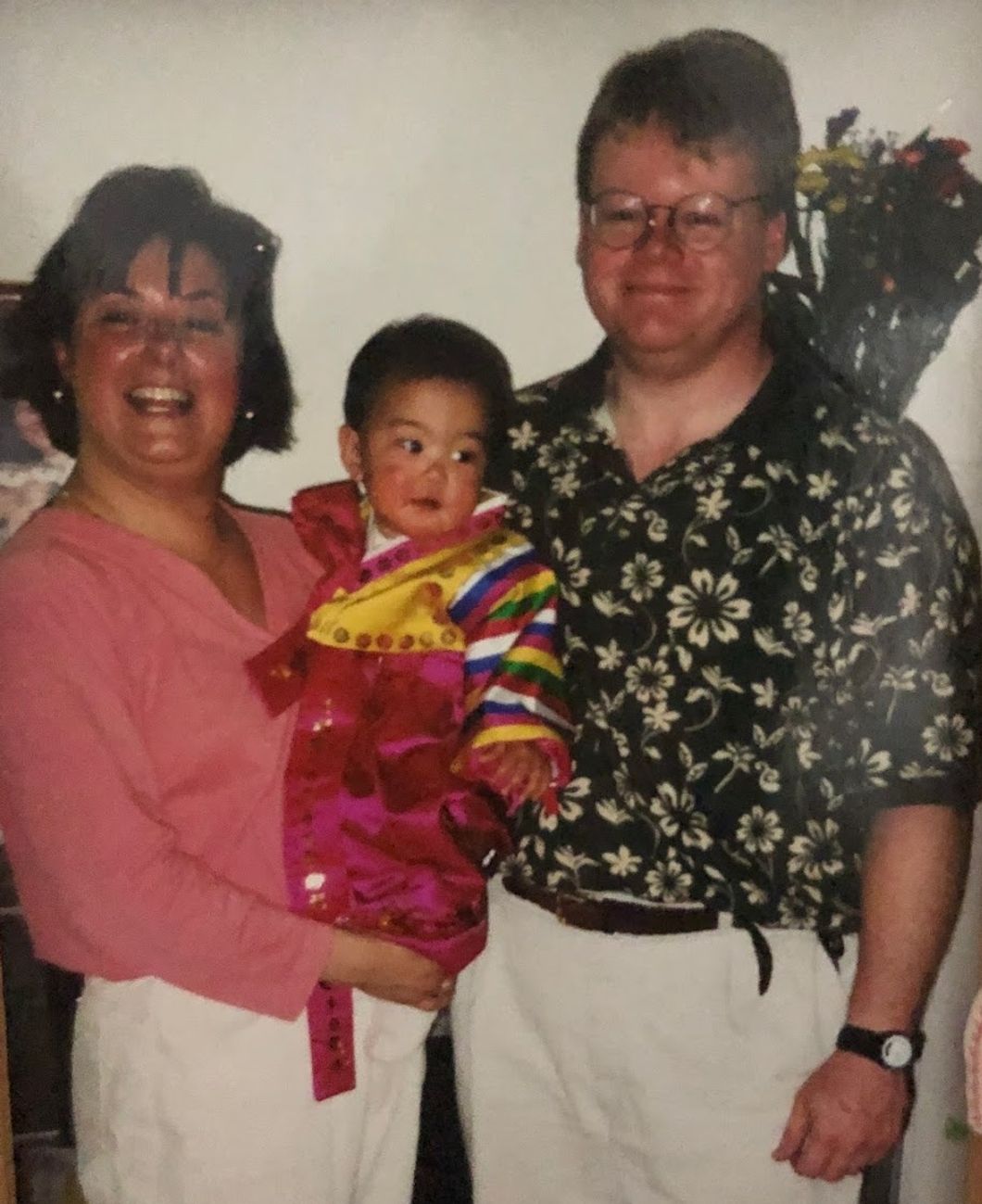

My mom tried to help me figure out my identity. God bless that small Italian woman, because she did. When I was five, she signed up my older brotherwho's also adopted from South Korea, to Korean classes. That only lasted about a year because it was tough juggling raising two young kids as a single mother. She made sure to buy not only princess books, but fairytales from around the world and books translated to English where the characters looked like me. In addition, we had a group of five families with adopted children from South Korea where the girls and boys were around the same age. This seemed an ideal way to expose our younger selves to people who had similar stories; however, at the age of 11 we were more concerned with who chose what game we played, rather than the alienation we felt in American society. On a large level I feel it was more like a focus group for the parents. But I appreciate the effort, and I still stay in close contact with one of the girls.

Then, the summer I turned 16, I traveled to South Korea with my mom with a trip planned through my adoption agency. In our group of about 17 families there was one mother that stood out. The stereotypical loud, unfiltered, white American woman. After her eighth or ninth outburst I remember turning to my mom and whispering, "I'm so glad that YOU adopted me".

This was not to say this other woman was a bad mother, however in that moment I realized how grateful I was to always have my mom there for me. My absolute queen.

My Goals as an Adoptee

For those who are adopted I wanted to share a list of ways that I have coped and tapped into this part of my identity and the small steps I take every day.

"The belief that I'd actually been wanted from the beginning, paired with the sure knowledge that my adoptive parents loved me, allowed me to grasp at self-worth, despite my doubts; to grow up and live my life free of the darkest feelings of abandonment." - Nicole Chung

1. Research

I actively search for books written by adopted Korean Americans and watched YouTube videos created by adopted Korean Americans. I nearly cried in the bookstore when I stumbled upon, All You Can Ever Know. A book featuring someone who looks like me and has a similar background. Although I have endless support from my friends and family, I found it very comforting to know I was not alone.

2. Joining A Group

This past year I joined the Asian American Society at PC. If your school has a club for your ethnic background I suggest sitting in on a meeting or joining. During my first meeting I found the courage to ask the other members if anyone was also adopted. In this way, I started creating a safe community for myself on campus.

3. Poetry

I am not a poet, however at times I feel it's helpful to write out my thoughts especially after intensely emotional days. One poem I recommend for your or your family is called, "A Legacy of Two Mothers". A reminder that adoption isn't just about loss and appreciating two lives that joined to create yours.

4. Controlling the Conversation

It's important to talk to friends, family or a therapist about adoption, but only when you feel ready. I hope that most of all, no one is pressuring you to start a search, be more in touch with your ethnic background, or share information. Remember, this is your life and conversation. You are in control.

5. Starting a Search

There are many reactions to being adopted, and for some, a search has been helpful in finding closure. I was born in a hospital in Seoul, South Korea and therefore, have some paperwork about my birth mother. No name and no photo, but something. This was enough to get me started on a search for my birth mother, and while this is not for everyone I found it giving me purpose because it was the beginning of filling a loss I've been living with my entire life.

6. You're Strong and Adaptable

There are a lot of things out of our control, and as an adoptee, being raised by a family that you don't share genes with is one of them. You may have had an atypical start to life, but that doesn't have to be the only thing defining you, and I'm sure you have adapted in small ways without knowing. For example, when I approach the register with my mom one of us will make sure to say, "We're together." This way, the cashier won't mistake us as not together and avoids awkward pauses, looks of confusion on their face, and rushed apologies.

I've personally found other adoptees to be some of the strongest people I know and are capable of handling difficult situations, so please remember that's a power you have always held.

What I have learned and wish I could tell my younger self is that there is no "right way" to be Asian American. Eating Korean foods or watching K-dramas is a choice that you can make for yourself, hell you don't need to be Korean to do either of those! Just as it's a choice to embrace your ethnic culture, it is just as okay to not be ready or want to accept it.