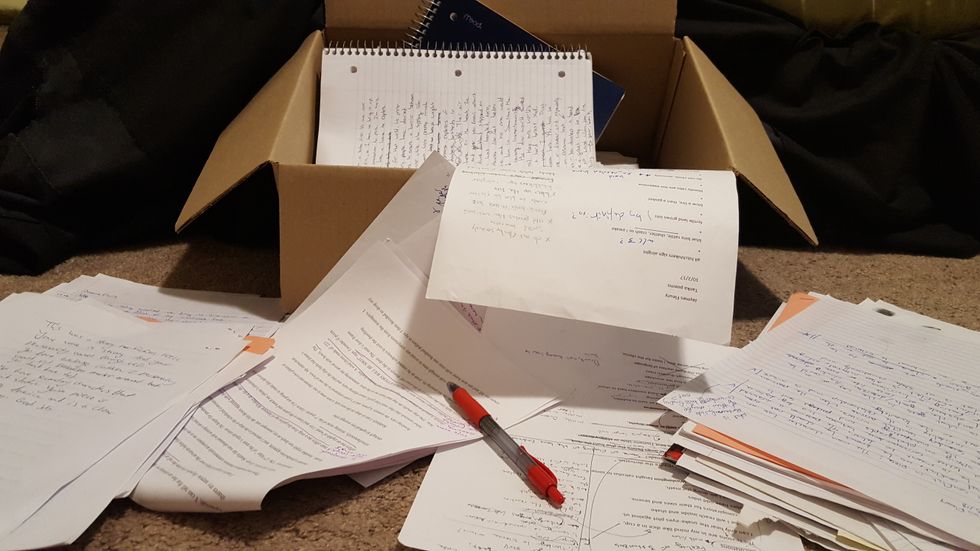

With the quarter’s end drawing ever-nearer, many graduating students like myself find themselves in moments of reflection and hindsight. We wonder what lies ahead and what new challenges we will be met with. I look at boxes crammed with five years’ worth of loose papers and spiral notebooks and can hardly seem to remember how half of those got there. I may never even open them again, but I can’t seem to toss them out. Not yet at least.

Every late-night essay, every work of fiction’s draft, second draft and polished piece, poems, non-fiction memoirs, doodles, and outlines create the layers of the paper strata. The bulk of it, however, at least as an English major, are the duplicate copies of singular pieces from in-class workshops.

If collected, the workshop notes would make up the bedrock of these paper stacks. They’re the notes in foreign scribblings and marginal suggestions that require the squint of an archaeologist to decipher and mull. Held above all other findings are those written by the professor, with marginal notes seeming to speak with greater authority. But they’re all just pieces of a larger record; not everyone is as significant a finding as the rest.

For those not in the know, creative writing pieces critiqued in workshop go through a similar process. Whether it’s a class of ten or of 25, classmates and professors will read through the piece ahead of time (assuming you turned it in on time and your classmates took the time to do so). The class huddles into an approximate circle (English majors) and every student subject to critique that day will have their work read aloud and examined before an audience. This is where the quirks and styles of each professor’s guidelines for workshopping come into play, still concluding in a similar manner.

In some clockwise fashion around the room, the author learns who spent how much time with their piece, what they “liked,” or if denied the verb, what they think is “working” for it. Once a complete rotation has been made, the professor will impart some of their own findings or at least mediate the ideas being shared. The whole process is a kind of parlor conversation, the author: a fly on the wall (although one can feel more like the proverbial elephant in the room).

The feedback, often repetitive but occasionally surprising the author with sage insight, is sent back to them in another xerox stack. If the author is lucky enough, there is a clear sense of revision laid out at their feet. But as a wise desert hermit once said, “In my experience, there’s no such thing as luck.” Obi-Wan may have been onto something, even though he was addressing the use of the force, feeling out the way of revision can seem just as enigmatic and strange.

The notes made sense in the moment, but at the desk, without the context, they seem to be without point or even downright unfocused conjecture. And yes, after five years of my own in-class roastings, I know when everyone suggests similar edits, there’s probably a good reasoning behind it.

Chances are, the author was aware of the short falling and does not require the same sentence to be underlined twenty different times. A classmate may offer that piece move in its tonal direction or align more with a certain feeling or theme - which may require an overhaul of the whole damn thing. But the workshop is over and it's another student’s turn.

The revision is up to the author, only to be critiqued in its final stage, the dreaded final portfolio. There are a few pieces in there that you’d rather not talk about, let alone turn in, last seen at an April workshop. Truthfully, every piece in there could use further revision, but it’s time to let go. And unless you retrieve the portfolio after the next break, that’s the last you’ll see of them.

A signal that the workshop went well is that the author returns to the file on their computer and continues to revise on their own time.

The majority, however, seem to find their way to the stacks in cardboard boxes.

Only now has it really dawned on me what the workshop is really for. We are not working towards the next Bishop or Douglas piece, we are usually working on our worst and more awkward moments of writing. I look now at the layers of the stacks and can see the change, slow but sure. My whole being cringes at some lines, titles, stanzas, and complete works of the past few years – it can feel like reading a personal journal, a sentiment worsened by the public nature of it all.

The word mortified comes to mind.

But none of it is our best work. We weren’t spending our time in an uncomfortably silent “circle” for hours in an attempt to become great writers. No, it was a way to prevent us from becoming bad writers who repeat mistakes and cliché. We all had to sit and stare at each other to agree on what could potentially work for a piece and what flat-out doesn’t.

It’s a bedrock we have made for ourselves, a way to know where we stand and are tripped up as writers.

I guess this is why I won’t be throwing away these boxes yet.