In light of the Syrian refugee crisis, in light of all of our recent conversations about borders and walls and displaced people, the idea that some lives matter more than others has especially informed the way we talk about and empathize with refugee communities around the world.

A product of the Arab Spring protests in 2011, and the subsequent Syrian Civil War, about 11 million Syrians have been displaced, both within their home country, and as refugees in foreign territory. Their journey for peace and stability has been a trying one, heavy with loss and a desperation to protect their lives and their loved ones. As this community continues to move throughout parts of Europe, the global response concerning their reception and well-being has been absolutely incredible. Though many European countries have been hesitant to welcome Syrian refugees into their countries, many are opening their doors, and we can attribute this to the enormous pressures that the global public is impressing upon the EU powers at be.

Syrian refugees are more visible than ever. One of the many countless examples was the photograph of a dead Syrian toddler who washed up on a Turkish beach. This tragic image went viral all over social media, and forced those not directly affected by the crisis to see the devastation in real and tangible terms. But what continues to be a reoccurring quality of the Syrian refugee reception are the ways in which global communities everywhere want to empathize with and shed light on all that Syrians are facing. And this empathy comes in many forms: Whether it is retweeting the image of a dead child, or volunteering at a local refugee camp, citizens everywhere feel moved to act, feel responsible in helping to tell the story of this moment in history.

So, the question becomes why are certain displaced people made more of a priority than others? As EU leaders rush to meet on Wednesday in attempts to address how and where they will distribute 160,000 refugees among their countries, why do African refugees and immigrants not receive the same kind of visibility and urgency in Europe, but also within a global context? For example, the UN estimates that about 3000 Eritreans leave Eritrea each month, and most head for Italy as a means of escaping the conflicts in their home country, as well as Eritrea's forced, indefinite military conscription, which demands that citizens serve in the army for an unlimited amount of time. Eritrean refugees must cross the Sahara Desert, which is an arduous and dangerous journey that has resulted in many deaths. If these migrants are successful in crossing the desert, they must take on another journey across a body of water. Two years ago one of the largest migrant disasters took place right off of the Italian island of Lampedusa. The ship was carrying more than 500 migrants, and of those lives 360 of them drowned. The incident helped to bring attention to one of the most deadly migrant journeys: the trip from North Africa to Europe. But the concern and outrage certainly did not last. Fatal Journeys, The International Organization for Migrations estimates that more than 3,000 African migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean since the start of 2014, but rarely do you see images of this devastation being shared on Twitter and Facebook. It is also important to make note of the hostile and racist immigration policies that are created in Europe as a means of deterring African migrants who are seeking safety and better futures for themselves and their families. Imogen Foulkes of the BBC writes “Until June of this year, Switzerland accepted avoidance of Eritrea's military service as a valid reason for claiming asylum, and the country now has one of Europe's biggest communities of Eritrean refugees. But Switzerland, like many European countries, no longer allows applications for asylum to be made at its embassies abroad, meaning that anyone wanting to make a claim must make their way, somehow, to Switzerland.” There is no doubt that these practices contribute to the regular boat tragedies in the Mediterranean. But most importantly, these policies are reflective of a collective European(and international) attitude concerning the welfare of Black bodies, and the attitude maintains that these bodies are disposable, that these bodies do not matter.

Syrians everywhere deserve visibility, deserve the opportunity to tell their story. But we must become wary of our unconscious and conscious attempts to lift up some communities and render others invisible or unimportant.

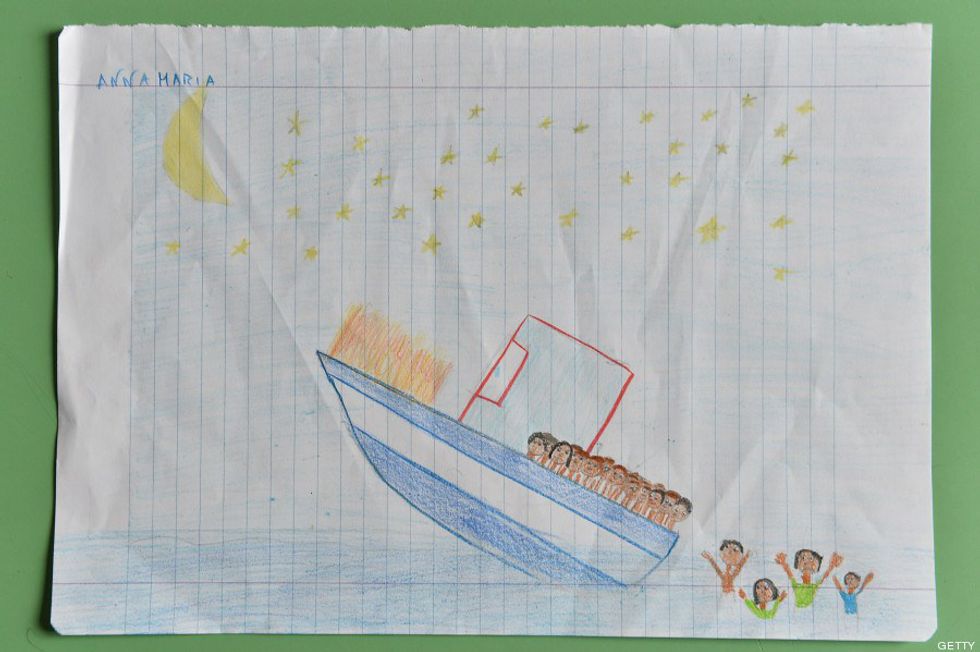

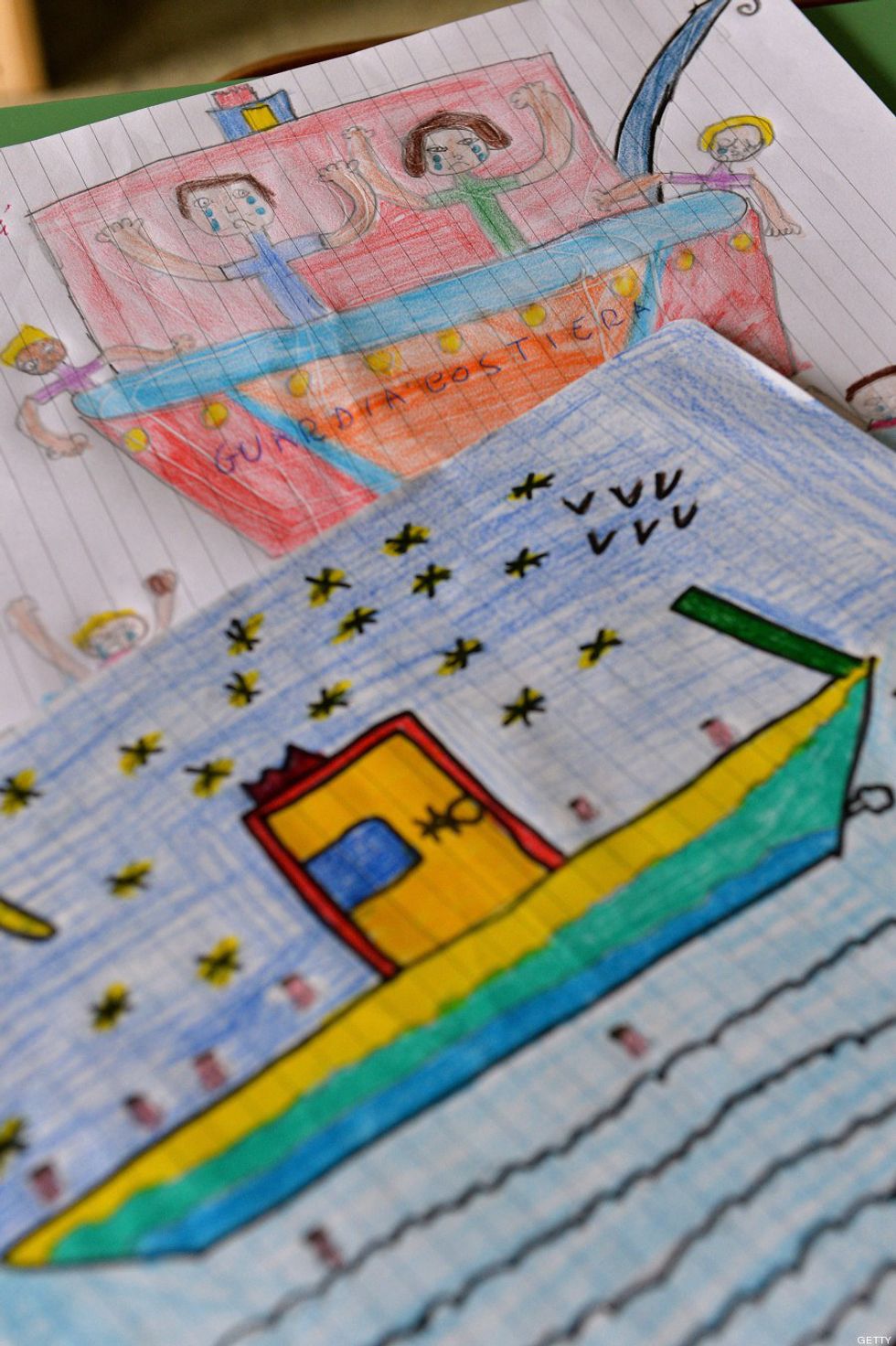

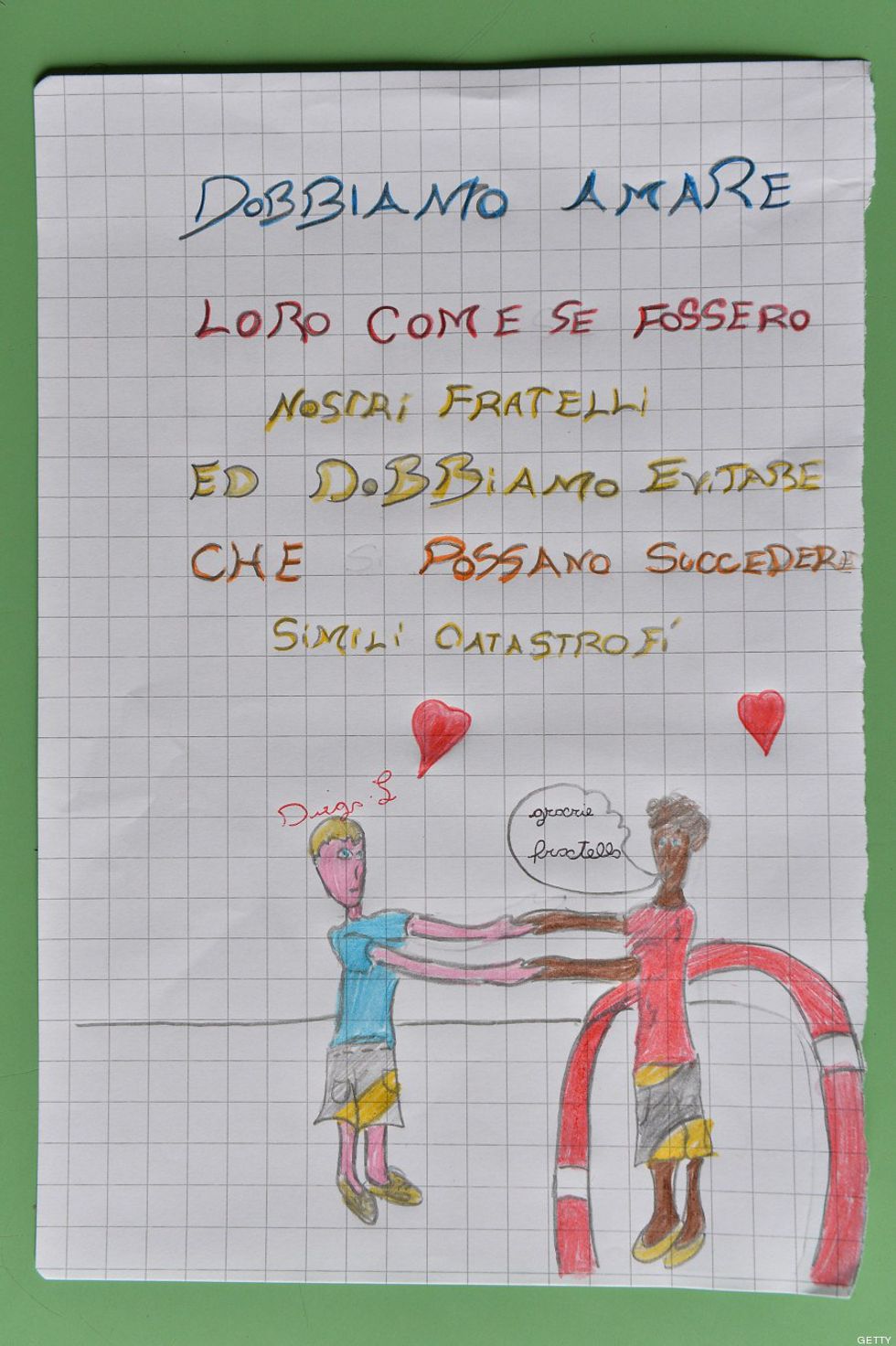

Rumi, the famous Persian poet, once wrote “the wound is where the light enters.” That line becomes especially relevant when you take a look at the numerous children’s drawings that were created in response to the unfortunate Lampedusa shipwreck. Students at Lampedusa’s elementary school, with the help of their teacher, were inspired to respond to the children who drowned on the boat that day, and they do so with colorful and heartbreaking clarity.

Here are some of the drawings below, courtesy of The Huffington Post:

Like the students in Lampedusa, we must find the space to include everyone in our narratives of injustice. Not one soul should be left behind.