I am 13 the first time I am cat-called on the street. A passing car full of boys at least two or three years older than me pause at a light to scream, “Oh yeah, baby!” at me and one of my close friends as we walk into a convenience store near my house. I am sweating from the blazing summer sun overhead and my hair is falling into my eyes. I am 13 and sex appeal is so far from my pubescent mind that I assume the shouts are aimed at someone else. But to my surprise, my friend nudges me and smirks. “Those boys were yelling at us.”

“Really?” I look up just in time to see truck full of leering grins and boyish limbs pull away from the intersection. I shudder without meaning to. I don’t know why, but I know for sure I don’t like what just happened. I cross my arms over the newly developing body I barely recognize which, in spite of my best attempts to cover it up, appears to be on some kind of display.

My friend smiles, looking so pleased I am baffled, “It’s such a confidence boost, isn’t it?”

“Oh.” I don’t know what to say. I can’t fight the uneasiness in my stomach, but I can’t say anything now without looking like I am unwilling to accept what was evidently a well-meaning compliment. I swallow. The desire to fit in trumps the urge to speak my real thoughts. “Yeah. I guess.”

Later I will learn that my neighborhood is known for having a terrible problem with street harassment. I will come to expect the shouts when I walk past my own block to the main streets, come to expect the loud blasts of horns out of nowhere that make me tremble from the nearness and the suddenness of the sounds, usually accompanied by lecherous facial expressions or gestures from the occupants of the vehicle. As I grow older, I try to dress in shapeless clothing, but that only decreases the harassment instead of erasing it. Finally, I learn how to tie my hair back and pull up the hood on my sweatshirt up to hide my face, keeping my ring-covered fingers stuffed in my pockets. It is only then, when I successfully erase any trace of my femininity for the benefit of the casual observer does the harassment cease. Subconsciously, I process that information. It is not my looks, my smiles, or my even my so-called sex appeal that draws these men in. It is my gender. My femininity. They are not yelling these things at me to give me compliments. They are doing it to remind me of what they consider to be my place. A sex object they can degrade in the streets, a weakling who couldn’t get back at them if she tried.

It’s true that I do not fight back against this kind of harassment. In fact, I call myself lucky. I have never been approached, never followed for more than a block or two, never pushed or touched. I already personally know girls who have not been as fortunate, who have faced horrors I do not have words for. I am lucky. This is what lucky looks like for young women in this country.

The other day, a man told me he thought that rape culture was becoming much less of a problem in our day and age. “There’s just more awareness now, so I think it’s really becoming less of an issue.”

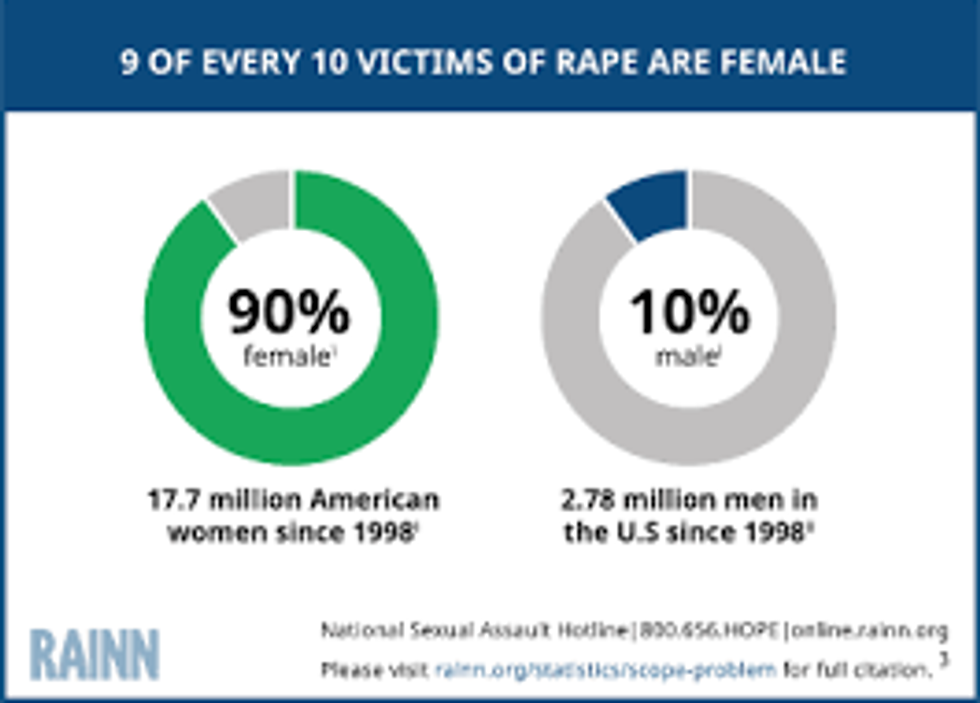

I did not say much to this. I told myself there was no point in trying to argue the existence of misogyny in a culture that too often overlooks the crime of rape to someone who obviously hadn’t experienced it enough to understand it even existed. I do not let my mouth shape the words for the statistics that rattle through my head automatically. Every two minutes, an American citizen is sexually assaulted. Out of one hundred rapists, ninety-seven of them will not see one day of jail time. Only 54 percent of rapes are ever reported. In this country, I am more likely to be raped then to get breast cancer. I told myself I was playing it safe, not harping on something that people are tired of hearing about, and I actually talked myself into believing for a moment that my lack of backbone was some kind of smart gesture in disguise.

That was wrong. Today in the news we see the case of Brock Turner, a young man who is getting by with a shortened sentence for a horrendous sexual crime that everyone knows he has committed. This story represents thousands like it, rape cases that do not get proper justice, if any at all. It is easy at times to look at these stories and tell ourselves we are not characters in them, that we are living a different life, in a different world. We tell ourselves, “She drank too much. Boys will be boys. She was wearing a short skirt. He made a mistake, just like we all do. That’s just how it is.” We excuse horrific acts of objectification, violation, and de-humanization and call them an unfortunate event. This article exists so that everyone can see, these stories are not just something that goes on in the newspaper. Even if a girl has not been raped, that does not mean she has not experienced sexual harassment and scarring experiences. These are simply my stories, and they are not uncommon. Almost every girl I know has similar ones, and many have far worse. I can’t tell those stories for them. But what I can do is tell these.

When I am around 12 I am playing around in the halls of a church (not the one I attended at the time) with two boys around my age. We are goofing off, exploring a building none of us are very familiar with, staying out of the adult’s way who are down another hallway that leads to a different building. The boys are brothers, and there is some obvious sibling rivalry going on. They push each other, yell when one gets in the way of the other, and wrestle constantly. Something the younger one does annoys the older one and he pushes him into an empty class room. Before I can say anything, he turns to me, grabs me by the shoulders and shoves me into the room after him, then grins. “You kids have fun.” He winks, switches off the lights, and slams the door shut. The room is pitch black. I can’t see anything, but I can hear the boy behind me breathing. Close to me. Too close to me.

I say, “Let us out,” but I know there’s no way anyone could have heard it because I am suddenly speaking in a whisper. Panic is filling me, and I don’t know what to do. I stumble to the door and locate the knob, but it won’t turn. I realize the boy on the other side is holding it in place. I slam my hand against the door, my voice returning in harsh whispers, fueled by sheer terror as the feeling grows in me that something is very, very wrong with this situation.

I start to scream, but then stop myself. If I scream, there’s a possibility that one of the adults might hear me and come investigate. And I know, deep down in the pit of my stomach, that I do not want that to happen. I am afraid of getting in trouble. I am afraid of that older boy’s wink, of his smile when he said, “You kids have fun.” I am afraid of being asked why I am on this side of the door.

I stop screaming. I slam my hand against the door. After what seems like an eternity but what was probably only another minute, the older brother opens it. He smiles. “What were you kids doing in there?”

He thinks this is a joke. It is not a joke to me. I feel so guilty, and I latch on to that feeling and the sturdy familiarity of it, but I will not recognize what else I am feeling for many years. Violation. I feel as though I have had something happen to me that is somehow not okay, but I can’t fully articulate the reasons and I am not sure I have a right to say anything. I don’t tell anyone about what happened. The boy gets away with it, because why shouldn’t he? It was all in good fun anyway.

When I am 7 I am playing with a group of boys in a McDonalds play place. My hands smell like chicken nuggets and grime-covered plastic, and my knees ache from scrabbling around on all fours through tunnels and over obstacles. And yet, I am happy. We have divided up into girls vs. boys teams, and the girls are winning the tag/hide and go seek/capture the flag hybrid we have invented. For some reason I am promoted to the captain of the girl’s team despite being shrimpy and small with wispy blonde hair and an non-intimidating features. I lead them proudly, moving past my usual shyness to embrace my new role. We are climbing one of the big platforms when the boys swoop down out of nowhere. The rest of the girls giggle and flee, but I am at the front of the line and have the farthest to run back to safety. The boys catch me. I kick, try to get free, but there are three of them holding me down. The leader wants me on their side of the playplace, so I am taken there, prisoner. I laugh, unafraid. It’s all a game. Just a game.

They tell me they want to torture me. This doesn’t bother me, I have three older brothers at home and am sure any form of teasing they could inflict would be nothing in comparison. I do not cringe at the word torture. I feel no threat in the fact that I am being physically restrained by three boys. I do not wonder if this is wrong, if this is not the good clean fun I should be experiencing. I don’t know any better.

The “leader” wants to kiss me. I do not mean for it to, but my face falls. This is not the family friendly teasing of a brother and sister who squabble but love each other. This is something different. This is…dangerous. I know that now, somehow. I can’t explain it, don’t even have the vocabulary to, but this, this is wrong, and I know it.

They see it bothers me. They choose it because of this. I struggle, so four boys have to hold me down. The leader moves toward me. Years later, I can still picture his face coming towards me, bending down as I lie on the floor, trying to work my limbs out of the vise like grips of the four boys that watch. I scream, but my shouts are lost amidst the noise of the other children playing. My stomach clenches. I am petrified.

I don’t know how I did it exactly, but pure adrenaline helps me yank one arm free, and I swing wildly, the kind of swing that is merely for show, not for impact, but I do hit one bony arm and my leg is free. I don’t hesitate. I knee the boy who leans toward me in the crotch as hard as I can. I don’t understand the anatomy whatsoever, but living with three brothers has taught me that this is a sensitive area, and a helpful one if the teasing ever gets to be too much. He falls to the ground and just like that the rest of the boys are in chaos.

I escape to the nearest slide and feel a rush as I exit to freedom. I do not look back. When I walk up to my mother, my tiny heart still beating wildly, she asks if I am ready to go, and I nod. I do not tell her what happened. I am afraid of getting in trouble for hitting, for throwing the first punch. I am afraid of being scolded for protecting myself, since I am not sure what I was protecting myself against. We leave and I never see those boys again.

When I am 13, a boy takes off his shirt and throws it at me and my friends as we pass each other in a mall, and then calls me a bitch for kicking it away from me so he has to walk farther back to retrieve it. When I am 17, a boy who is not my boyfriend slides his hands down my back a little too far and leaves them there, and when I ask him to stop, he says, “Why?” I don’t remember what I said, but I remember what I thought. Because I’m uncomfortable. Because you have no right to touch me. Because I’m a person and I’m asking you to stop. When I am eighteen, a much older man tells me how much I’ve grown up in the last year as his eyes rake over my body and I don’t know who to tell or what to say to get him to stop. When I am nineteen my friends and I take turns sitting in cafés a block away while the other one goes out on dates, just in case things get ugly or we become worried we are being forced into a situation neither of us wants. We stand in for each other’s 911-calls, because we know from experience, the police won’t do anything until he touches you. They don’t know, I guess, there are a lot of ways to make someone feel violated without being touched.

The other day as my friend and I were walking down the street in a nice neighborhood, a man drove past in an open jeep with a bunch of little boys in the back, probably around seven. As we passed, the boys yelled, “Hey chicks!” Their little voices all chimed in together as they waved ecstatically in their tiny baseball hats and jerseys. The man driving laughed. I tried to see this as innocent as it could be, instead of training for something much darker. I tried not to imagine if these little boys ever tortured their female classmates with kisses, or wonder if they would, in later years, grab a girl’s arm too tight when she tried to walk away. I tried to tell myself the dad didn’t know what he was doing when he taught those kids to yell at girls on the sidewalk like they’re a show for their pleasure. I tried not to believe the boys took pride in it, but I knew they did.

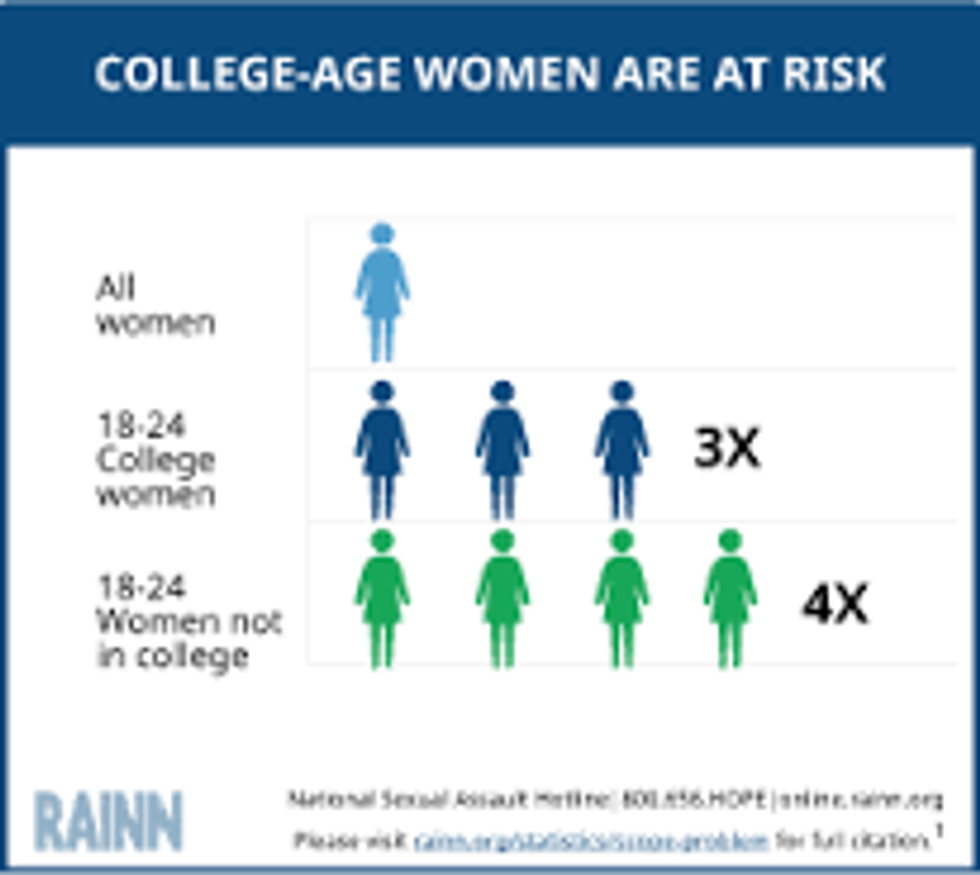

This article is long, but it could have been longer. I had to pick and choose my stories. There are many more. And I was lucky. I know women personally who were far less so. I was 9 the first time one of my friends was raped. As a 9-year-old girl, I learned what that meant. I was so young when I learned what could happen to me, I barely remember living without the fear of it.

These stories I’ve told are commonplace, but they are not normal. They’re terrifying, they indicate a horrible mindset about women in this culture. I know there will be and are some who will see these stories as nothing, and maybe in one way they’re right. I walked away from them, and maybe I didn’t really get hurt. Maybe I was one of the lucky ones. But what does that say about who we call lucky? The ones who get to walk away without shame? The ones who may have bruises on her arm from where a boy or man held her down but who managed to rip away in time. The women who said no, and then said no louder, and on the third try were told they were finally listened to even as the man who was making them so uncomfortable called them a prude or something worse for saying anything at all. I know these stories are not as dramatic as they could be, but they do display a pattern of disrespect and boundaries being crossed, and that lack of basic respect for boundaries and the people who set them are often at the crux of sexual violence. It is these and stories like them that should inspire change in the world, that should move everyone to see these issues as pressing and prevalent, and still very much in need of further attention.

To the man who told me rape culture was the thing of the past, that awareness had erased it, I want to let you know, you were wrong. It still exists. Terrible things do not stop existing as soon as they are known. They must be eradicated and undone. It will take time, it will take a re-educating of our sons and daughters, it will mean new boundaries, and no victim-shaming. It will mean understanding and love instead of ignorance and prejudice. But I still do believe change is possible. Let this be the generation of victims that stops the fear. Let this be the generation when we replace the words “made a mistake” with “raped and violated a fellow human being.” Let this be the generation of people who seek safety, understanding, and respect for every individual, regardless of race, gender, or sexuality. Let this be the generation that actually begins to make our culture of misogyny and violence a thing of the past. Let our generation be among the last that can tell these stories and call them nothing.