The invisible plague of genetic disorders has unfairly limited or ended millions of lives before they even start. Genetic disorders are the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States, making them responsible for roughly one in four infant deaths. Half of the mentally disabled population have their genes to thank for their condition. They are given a difficult burden by the arbitrary genetic lottery, and they are not alone. Many people are even morally limited by their genes:

Willingness to commit antisocial acts, including lying, stealing, starting fights, and destroying property, is partly heritable ... Most psychopaths showed signs of malice from the time they were children. They bullied smaller children, tortured animals, lied habitually, and were incapable of empathy or remorse, often despite normal family backgrounds and the best efforts of their distraught parents. Most experts on psychopathy believe that it comes from a genetic predisposition.

As it turns out, "most experts" are right in this case. Psychopathy is about 50% heritable, like most other personality traits. Your genes determine a significant part of who you are without your input.

Genetic engineers have been working for decades to combat genetic disorders and give a better chance to those who have been unfairly punished by nature. But, as it turns out, genetic engineering is hard. Really hard. It is also expensive and time-consuming, which is a huge obstacle for genetic engineers. As Bruce Conklin pointed out, "It was a student's entire thesis to change one gene."

However, within the last five years or so, a revolutionary new gene editing technology emerged which makes gene editing cheaper, faster and easier than ever: "CRISPR-Cas9 editing."

For over 30 years, scientists have been confused by a certain part of DNA in bacteria. The same pattern would occur over and over, alternating with unique ones. They named it "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats," mercifully shortening this convoluted phrase into the short and catchy acronym "CRISPR."

Recently, scientists realized that these CRISPR patterns matched the DNA of certain viruses. They figured out that the bacteria store virus DNA to identify viruses in the future, like antibodies in our immune system. Cas9 is a protein that cuts DNA wherever RNA tells it to. Normally, this is used so the Cas9 can find and delete any unwanted virus DNA when the same kind of viruses attack in the future. However, scientists have realized that it opens up an incredible opportunity for gene editing:

A system where you can send one protein to cut anywhere in the genome just by giving it a chunk of RNA is really useful for molecular biologists . . . CRISPR lets you make a precise cut in DNA, so you can use it to knock out a gene, or even trick the cell into inserting a gene.

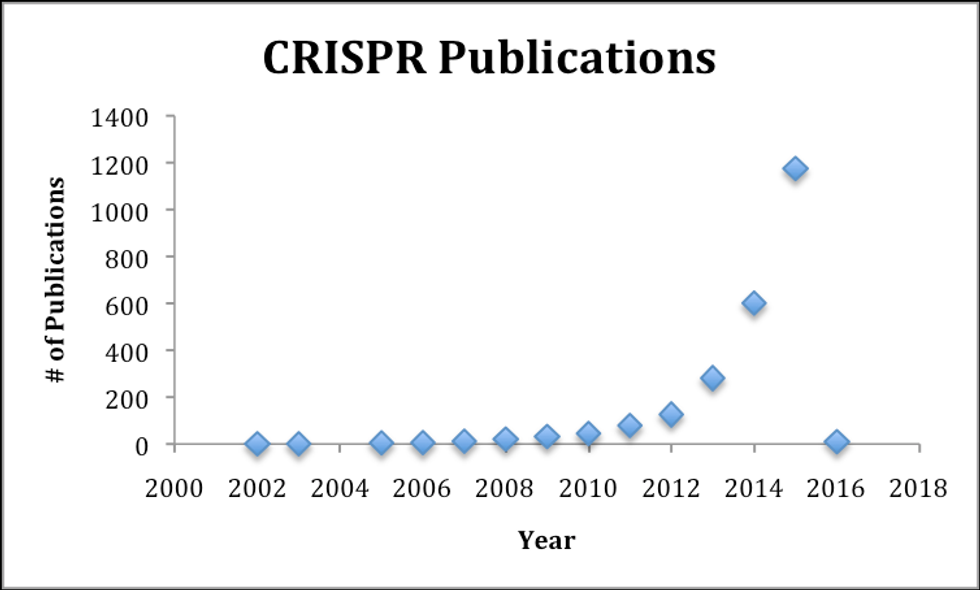

New applications of CRISPR are popping up everywhere as research increases at an exponential rate:

The 2016 point on that graph is zero because that graph is from 2015. Considering that CRISPR editing is a revolutionary step forward in genetic engineering, 2016 is likely to continue the boom in CRISPR research.

Signs of the possibilities that CRISPR opens up for us are only starting to pop up in news headlines. For example, the first few human trials to use CRISPR to treat cancer were approved this year. As CRISPR spreads, it will enable us to combat problems which our ancestors saw as unsolvable or "part of human nature."

Like any of the technologies that have given us an unprecedented amount of power over certain situations, CRISPR is bound to lead to serious ethical debates. Ideally, legal restrictions will make sure that this new technology is only used for the right reasons. But there are plenty of right reasons to use it for, which is likely to give millions of people their lives back after their genes tried to steal them.

For more information on this subject, check out some of the following resources:

Kurz Gesagt: "Genetic Engineering Will Change Everything Forever - CRISPR"

Nature: "CRISPR: Gene Editing is Just the Beginning"

Cody Stewart via Odyssey: "CRISPR: What It Is And Why You Should Care"

The New Yorker: "The Gene Hackers"