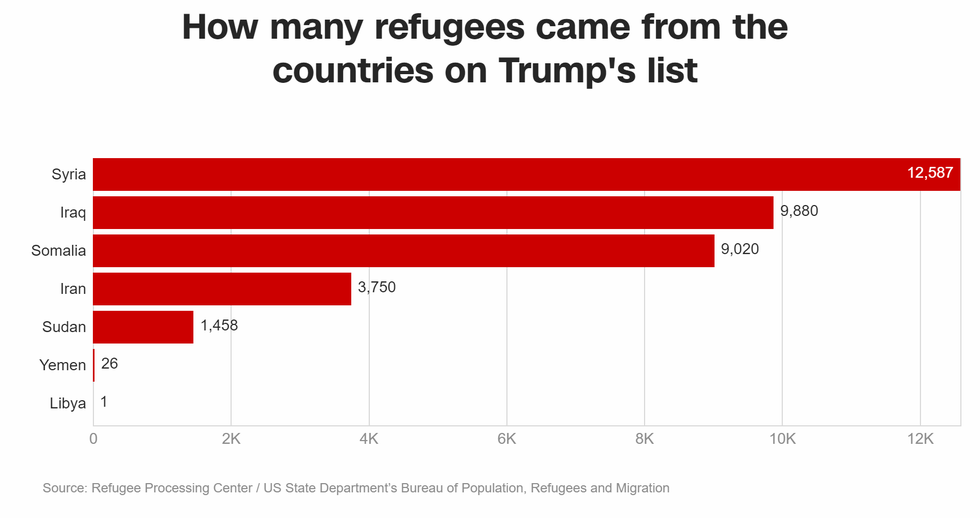

Within his first two weeks as President of the United States, Donald Trump signed an executive order barring citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States of America for 90 days and suspending the refugee program indefinitely. Titled the “Protection Of The Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into The United States,” the order bars all people from so-called “terror-prone” countries (Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia), thus fulfilling his campaign promise to tighten borders and stop certain people from entering the United States, saying “we don’t want them here.” This order has affected everyone from employees in the US, to families, to students, to refugees.

In addition to the refugee suspension and travel ban, the executive order also cancels the Visa Interview Waiver Program, which allowed frequent travelers to the US to renew their visas without an in-person interview. Under this new order, all visa holders must have an in-person interview to renew their visas.

Through this executive order, Trump is suggesting that the current screening process for refugees is not thorough enough, saying, “we want to ensure that we are not admitting into our country the very threats our soldiers are fighting overseas.” California Congressman Tom McClintock called the Obama Administration’s refugee screening “very haphazard,” claiming refugees were let in “simply [due to] the word of applicants.”

With this new call for “extreme vetting” of refugees and immigrants, it’s easy to fall under the same worldview of McClintock and the Trump Administration. However, the reality of the refugee screening process is one that is robust and exhaustive, not haphazard.

So what does the refugee vetting process actually look like in the United States?

First, the United States government defines a refugee as someone who “has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion,” according to the Pew Research Center.

McClintock claims that refugees have been let in simply due to their word, but this is incredibly unfounded. Word alone is far from enough. Not only do potential refugees spend an average of 18 to 24 months of already-extreme vetting, most of this is actually done outside of the United States. The whole process can take up to three years, and even then the individual’s application can be rejected. In 2015, fewer than 1% of applicants were granted refugee resettlement.

*Note that the following steps occur BEFORE the applicant even enters the United States.

A potential refugee must first register with the United Nations and go through UN screening.

This includes inter-agency security checks, biometric security checks, face-to-face interviews, security database checks, and background checks. The UN decides which cases are most vulnerable and refers them for settlement. If they have committed even one crime, their case risks being thrown out; if this crime is violent, their case is closed and they do not qualify for refugee resettlement.

If refugee status is granted by the United Nations, they are referred to a country for resettlement.

Only 1% of refugee cases are referred; the rest can spend years waiting in refugee camps for resettlement.

If the refugee is referred to the United States, they face further vetting. This process involves, at minimum: eight federal agencies, six databases, five background checks, four fingerprint and biometric checks, photographs, three in-person interviews, and two inter-agency checks.

During this time, the refugee is placed in a detention center.

Hundreds of thousands of people are placed in refugee detention centers and closed immigrant camps around the world, where they can face conditions below human rights standards, restrictions in movement, an unknown and not-guaranteed immigration date, and thus an unknown fate.

Conditions within detention centers are often prison-like and can even be abusive.

Refugees can be placed in overcrowded and unhygienic spaces alongside convicted criminals, and be given little to no protection. Access to legal counsel is often sporadic and unreliable. Children are often detained with no access to school or learning of any kind. Men and women can be placed in the same facilities, yet at the same time families are often split apart. Refugees are dependent on resources provided by the detention centers (including everything from food and water to blankets, heat, and clothing), which frequently face shortages and cuts. Refugees are not able to work or provide for themselves, and if they try to they risk police brutality and their cases being thrown out.

In the further vetting given by the US government, the refugee’s name is put through law enforcement and intelligence agency databases to check for terrorist and criminal history.

Additional background checks for persons aged 14 to 65 are also employed.

Fingerprints gathered during these checks are screened against FBI databases, Homeland Security databases, and Defense Department databases with information gathered from operations overseas. These databases hold information regarding whether the refugee applied for a visa at a US Embassy, past immigrations, and watch list information.

If the applicant is Syrian, an additional review is required. During this additional review, the application goes to a United States Citizenship and Immigration Services specialist, who provide further vetting. During this step, if the refugee’s case is found to have national security indicators, the case is given to the Homeland Security Department’s fraud detection unit.

The case then goes to US Immigration Headquarters, where Homeland Security gives extensive in-person interviews.

The questions during this process are extremely invasive, and refugees and asylum-seekers who have already gained entry to the US have said that at the end of the process, the US government knows them better than their family and friends. Questions during this part of the process seek to prove that the individual is not lying about being a refugee – that they, in fact, are fleeing danger and have true fears of persecution and life-threatening circumstances.

As described on Vox, the questions ask the applicant to relive the incredibly minute details of the worst days of their lives, “Why did the security forces detain all the men coming past the checkout in Damascus that day? Describe the room — how were you hung up? Where did they attach the electric cable on your body? Did you ever see your sister again?” Relationships to other people are described, daily lives are described, darkest moments are uncovered. It is the job of the legal advisor to gain each and every detail to prove credibility, and the job of the hopeful refugee to remain as calm and transparent with the details as possible. As described by one of the interviewed refugees, “I was telling the truth the whole time, so my story was straight, but other people who had slipped up and given different details were rejected on the spot…I was asked questions you could not believe and could not think of, and even asked questions about my life that I did not know the answers to. They even asked about one of my uncles who was dead for a couple of questions.”

These interviews can last anywhere from one to six hours for each of the minimum of nine interviews, and all of these interviews are done before the refugee sets foot on US soil. For many Syrians, this has meant interviews often in Jordan or Turkey, for example.

If the applicant gets past these interviews, Homeland Security approval is then required.

After Homeland Security approval is gained, screening for contagious diseases is done.

After screening for contagious diseases, refugees are given a cultural orientation class and matched with an American resettlement agency.

After matched with an agency, the refugee goes through multi-agency security checks before boarding the plane to the United States. Once this plane lands in the US, they undergo a final security check at the US airport.

Upon entry to the United States, refugees can be placed back in detention centers while they await settlement.

Refugees are placed in these detention centers unless they have family others to stay with. Resettlement agencies house refugees for their first 90 days, providing them with food, shelter, medical care, and other necessary services such as contact with an immigration network, job agencies, and state benefits. Refugees are expected to repay the United States government for their plane tickets six months after arrival.

After one year of living in the United States, all refugees are required to apply for green cards, which then triggers another set of security procedures within the United States government.

--------------------------

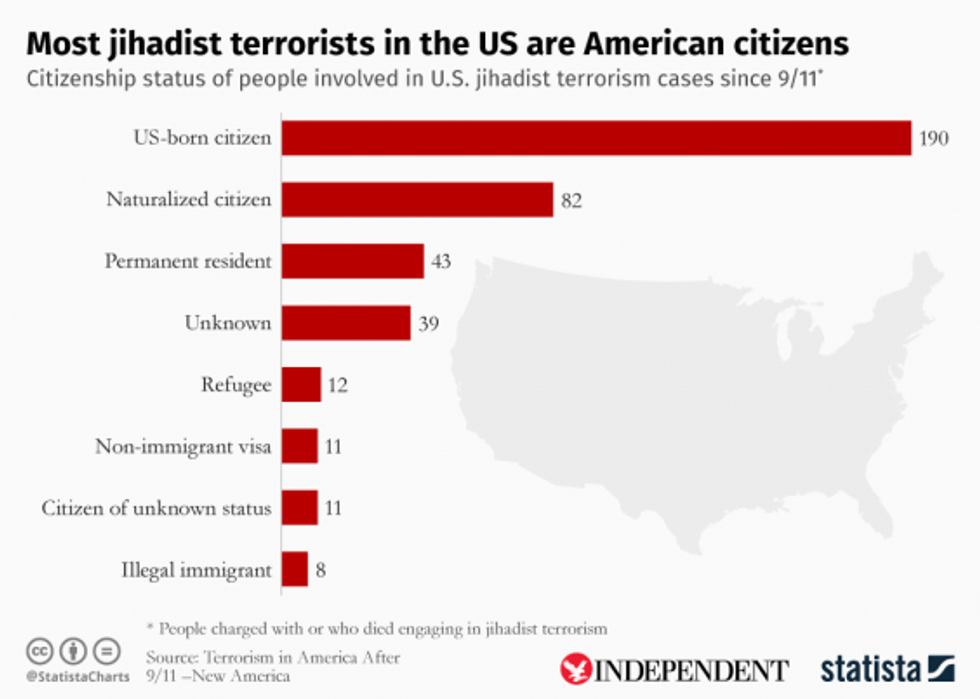

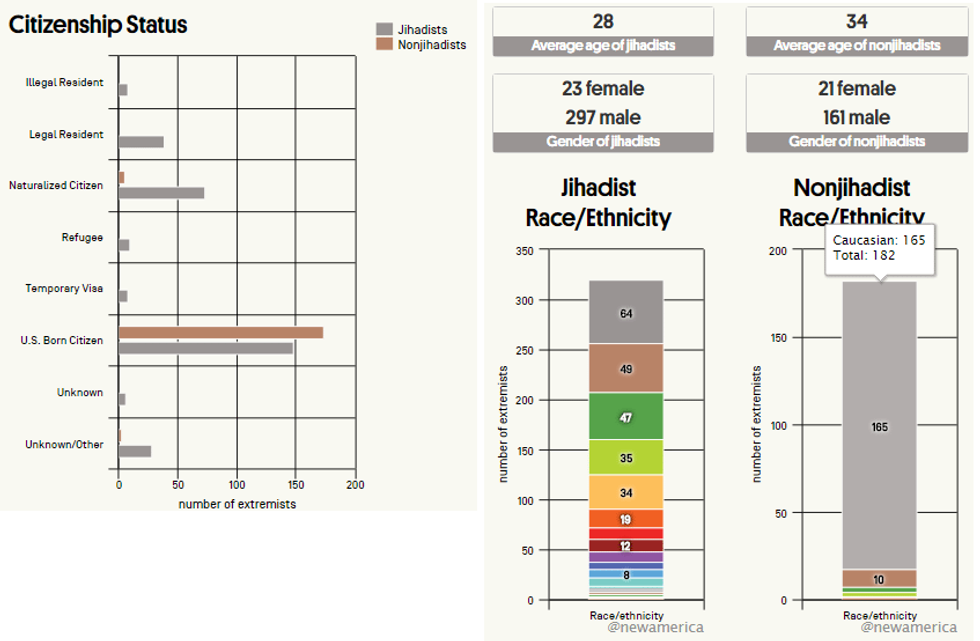

The United States already employs extreme vetting for refugee settlement, and this vetting is constantly evolving and being added to. Refugees are the most vetted group to be allowed entry to the United States, and they remain on the radar of United States intelligence agencies even after resettlement.

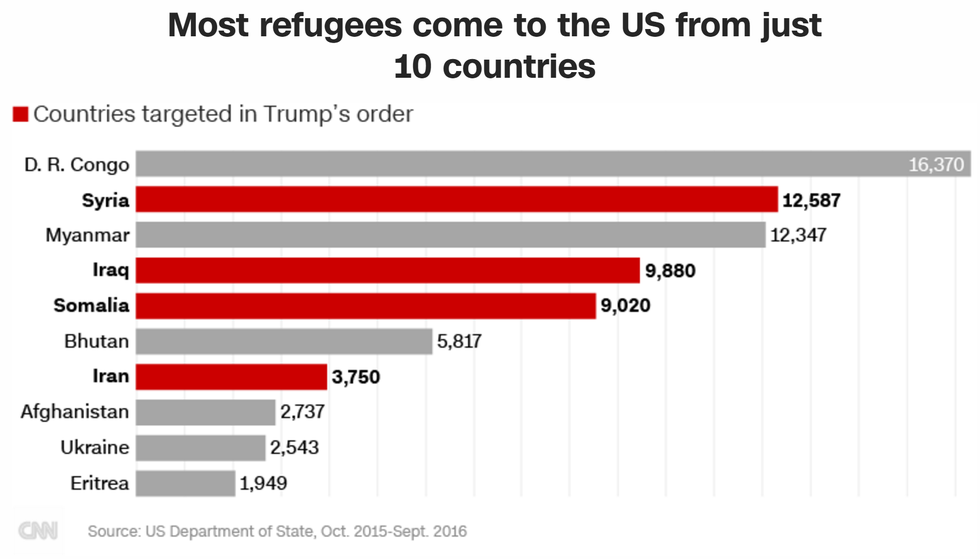

Refugees are constantly coming from different parts of the world, and even those that Trump has banned from entering the United States are not the major concerns for terrorism for the United States.

The irony of Trump's executive order is obvious: those who are coming from places that put them in the most danger are the very same that the new US Presidential Administration are pointing to as the most dangerous. 99% of those who seek refuge in the United States are rejected; refugees are not just allowed in without thought.

The notion that those who have faced years of vetting, detention, and separation from family and friends, and denial of access to basic resources would turn around and go against the very country that has given them a new chance at life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These are the very values the United States is founded on, yet these are the very values that are being denied to those who are the most weary, those who have spent much of their lives yearning to be free.

The vetting is already extreme, and suspending the refugee program is not the solution to the terror in our world.