We're always searching for exoplanets, and it looks like we've found one that's probably as close as it could possibly be. In a paper published in Nature on August 25, researchers shared their observations of what looks like the closest planet outside our solar system.

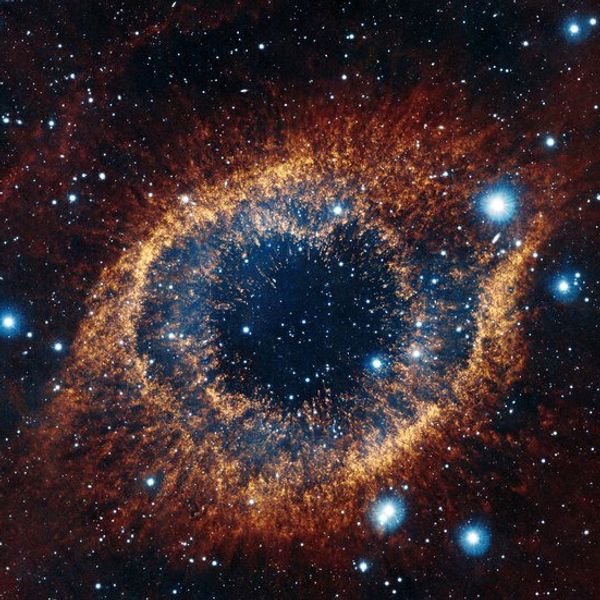

Now, the universe is pretty huge, and we're pretty small, so distances in space are pretty astronomical. The closest star to us, obviously, is the Sun. But outside our solar system, the next best thing is Proxima Centauri. It's a red dwarf, the smallest, dimmest, most long-lived type of star and the most common in our galaxy. Red dwarf stars are generally difficult to observe because they're so small and dim, but Proxima Centauri is the most well-observed star of its kind because it's really close by -- only 4.25 light years away! Of course, this small number doesn't mean it's really very close; 4.25 light years is roughly equivalent to 40 trillion kilometers. That's still pretty far, and it would take thousands of years to get there with current spacecraft.

Besides its importance as the most easily observable red dwarf star, Proxima Centauri also looks like it's got some company -- scientists have found evidence of a planet in its orbit. Dubbed Proxima b, this exoplanet has about 1.3 times the Earth's mass and fits snugly into its star's habitable zone.

Now, Proxima b may not be our best candidate for extraterrestrial life, despite its position in relation to Proxima Centauri. The habitable zone is, after all, just the region in which a planet can sustain liquid water on its surface. Just because it can, doesn't mean it will; Mars and Venus are within the Sun's habitable zone, but they're not exactly brimming with water, let alone what we'd call habitable.

We don't know much about Proxima b's atmosphere, or whether it has a magnetic field to protect it from radiation and stellar winds -- Mars doesn't have a magnetic field, so while it used to have a significant atmosphere, much of it got blown away.

Proxima b's close proximity (7.5 million kilometers) to Proxima Centauri might also render it tidally locked. That means it would orbit with one side permanently facing the star and one side always facing away, just like the Moon does in relation to the Earth. As one might imagine, the options of only boiling hot on the near side or freezing cold on the far side don't provide particularly pleasant living conditions. However, there might be small regions where the temperature of a tidally locked planet might make those areas habitable, and heat could be redistributed to some degree with oceans and an atmosphere. Those are a lot of factors to consider, and, of course, we don't know whether or not the planet is actually tidally locked.

Despite the conundrum that is Proxima b's habitability, the finding is still really important. This is the closest exoplanet to our solar system, and unless a rogue planet is whizzing around nearer to us, this is the closest an exoplanet can even be. Its proximity means that we can observe it more easily than we can many other far-flung exoplanets; if the planet passes directly in front of its star, we can learn tons of stuff about it such as its atmospheric composition, and perhaps even directly image it.

So maybe we won't be meeting aliens next door, but figuring out that there's a house there at all is a pretty big deal. Whatever we learn about Proxima b, the fact that we get to learn anything about it at all is super cool. I, for one, can't wait to get to know our neighbor.