It’s 5:45 on a Thursday night when I enter the Cinépolis movie theatre on 23rd Street in Chelsea. I’m 15 minutes early but I wait with patient anxiety in my seat for the previews to start before the six o’clock showing of Wes Anderson’s newest: "Isle of Dogs."

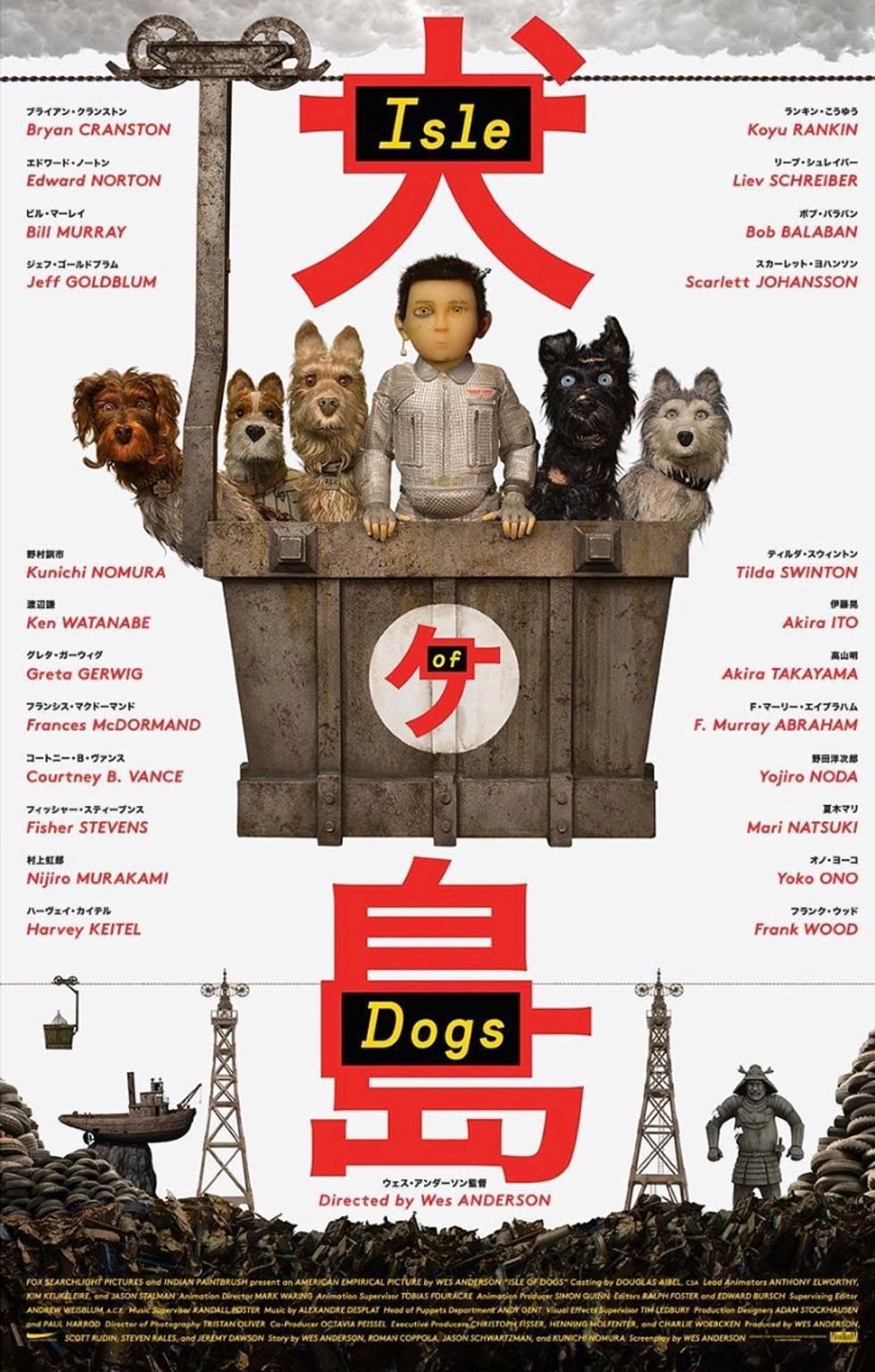

Like many of Anderson’s previous movies such as "Moonrise Kingdom" and "The Life Aquatic," "Isle of Dogs" is a visually stunning romp that juxtaposes dark themes with wit and dry humor to create fantastic effigies of human existence. It follows twelve-year-old Atari in his pursuit to reclaim his dog, Spots, after his uncle, Mayor Kobayashi, exiles all canines to "Trash Island," and the subsequent uprooting of a conspiratory plot to be rid of the dog species entirely. What makes "Isle of Dogs" stand out, however, is the care and precision with which Japanese culture is handled—especially in the shadow of Hollywood’s belligerently disturbing "whitewashing" notoriety.

While the movie is currently held in high regard, with a rating at 91 percent on Rotten Tomatoes and an 8.2 out of 10 on IMDb, I have come across some disgruntled reviews brandishing the film as cultural appropriation, a complete fetishization or Orientalization of Japanese culture, or succumbing to a "white-savior" narrative.

It’s understandable to get upset from the offshoot: Anderson is, in fact, a white man making a movie about a fictional, futuristic, Japanese society. However, it is important to note that there is a distinct difference between "fiction" and "fetishization." After careful consideration, analysis, and research into various Asian-American reactions to the film, it seems reasonable to claim that "Isle of Dogs" is nothing if not a respectful and heavily researched exploration of cultural sensitivity, representation, the consequences of "Othering," and the power of language.

In her article in The New Yorker titled “What ‘Isle of Dogs’ Gets Right About Japan,” Moeko Fujii expresses her appreciation for the film, a film which places her native language at the center of attention, and actively neutralizes the only American/Native English speaking character. She details the accurate portrayals of the intricacies of everyday life in Japan and her pride in being the only one in the theatre to catch on to subtle jokes that English speakers would never understand.

Wes Anderson and co-writer Kunichi Nomura, along with the multitudes of Japanese actors and creators who were involved in the making of the film, understand the shortcomings of Asian and Asian-American representations in the entertainment business. They have proven that they can work against that with subtle subversions like the Japanese characters’ understanding of Tracy, the foreign exchange student’s English, but their choice to remain as interlocutors in their own language, the fact that the ultimate savior of the whole movie was the Japanese hacker from the newspaper club, and not to mention the obvious narrative of the oftentimes violent "Othering" of a group that is in some way different to the assumed norm (i.e. the exiling and encampment of the dogs).

These methods are forceful and important—to which Fujii relates: “One of the most potent shots in the film is of graffiti on gray cement. A large black scrawl asks, 'Douyatte bokura wo korosu tsumori?' 'How on earth do you plan on killing us?' For most viewers, it’s a mark on the wall. For Japanese ones, it’s a battle cry.”