Black Lives Matter does not

mean that white lives do not. How many times must that point be made

clear? How many variations of that concept must go viral before the

phrase is defined by those who own it rather than by those who dismiss

it? Listen to the activists, and read the words of the leaders of the

movement. The notion that Black Lives Matter implies

white inferiority does not derive from them, but rather through the

agendas of those who wish to deny that a problem exists.

The movement should not have to

constantly explain the meaning of those words. It was not the

protestors and activists that incited the war over semantics, it was

their critics. The inception of the All Lives Matter adaption of the chant was not due to frustration over the violence

that exists in our nation, but rather as a response to undermine the

initial plea for the protection of black life. All Lives

Matter is used almost exclusively as a response to Black

Lives Matter. This does not address violence; it silences those

actively seeking justice and peace.

Yet those who pontificate the All

Lives Matter slogan through speech and hashtags wonder why

these three words upset so many people as if they are persecuted for

the literal notion that the lives of everyone hold significance.

Again and again, black activists are charged to explain why it is the

context that surrounds these words and not the literal meaning that

warrants their rejection of the phrase. However, if literal meanings

stand as the only reflection of these competing mantras, then the

question should be asked of the critics: what is so objectionable

about the belief that the lives of black people matter? The only

premises that offer explanations behind the rejection and offense toward this tenant

are either the denial that racism still exists or the view that black lives

do not matter in confirmation that racism is alive and well.

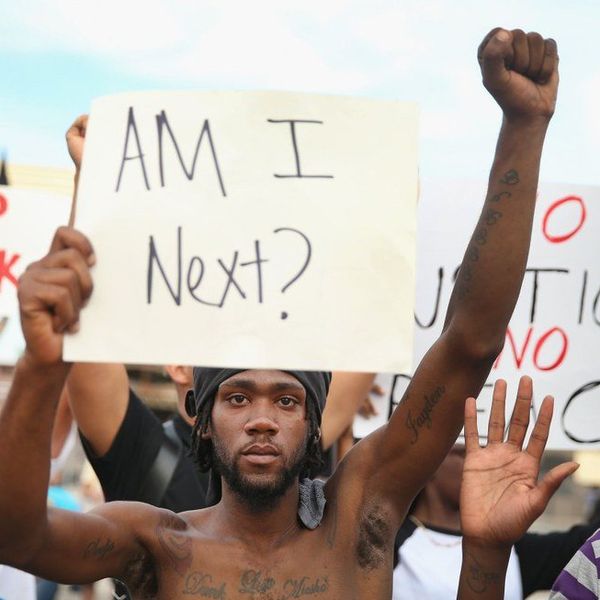

The acceptance of the perseverance of racism in America is difficult. It is not even comparable to facing the actual realities of its existence, but difficult to acknowledge, nevertheless. Our early education often seems to offer a post-racial view of our society, as one that has conquered Jim Crow and defeated inequality by placing a black man in our nation's highest office. It is an attractive delusion, but while pictures of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Frederick Douglass are displayed on the walls of our schools every February, we are not firmly reminded of the stark difference between being white in America, and being black.

I have the privilege to live under the convenient delusion of colorblind institutions, because I will continue to live regardless of whether that delusion is addressed. Alton Sterling and Philando Castile did not have that privilege, and now they are dead. It was not until the 2014 decision not to indict the man who killed Michael Brown that my delusion of this post-racial nation was finally shattered.

My whiteness and the privilege attached is not something I am ashamed of. It is a predetermined factor of my existence. The shame of white privilege is on the culture that fosters its reality and only extends to me if I deny this privilege and refuse to join the collective voice that calls for an end to the violence and oppression against those who share different experiences than I do.

We, as white people, do not need to assume that calling out white privilege is an attack against us.

We, as white people, do not need to assume that acknowledgment of racism is an attack on us.

We, as white people, do not need to assume that Black Lives Matter is an attack on us.

When we operate under these assumptions, it is because we choose to, not because they are true. Our privilege is not an indictment upon ourselves, but it does entail a responsibility to listen.

The clear miscommunication between Black Lives Matter activists and white America, which often seems intentional, is an equally clear indication that we have not listened to the frustrations of the black community. We don't know what it means to be people of color, yet we often assume the capacity of dictating their experiences to them. We refuse to validate their grievances, and when faced with black death after black death, we search for any excuse to justify the killings. The continued racism from which we as white people face no imminent danger is uncomfortable for us to face, and so we keep the delusion alive as more black people die. We make black life expendable by propping our denial of their circumstances, thus all lives do not truly matter.

To assess the misleading perceptions of Black Lives Matter and prove the fallacy behind All Lives Matter, we need only to analyze the response to this week's tragedies and the seven lives lost. We witnessed a detrimental inconsistency, one where activists were held to a standard far exceeding that of those in positions of power.

When five police

officers were killed, we blamed a movement. The movement did not call

for these murders, the movement did not commit these murders, yet

"the blood was on their hands" regardless. We chastised

Black Lives Matter activists for any satisfaction over the

Dallas shooting, but there doesn't seem to actually be any

satisfaction within their ranks. Rather, the expressions from those

who embody Black Lives Matter were of mutual grief over

the continued violence.

The true reality of the Dallas shooting is that both the activists of Black Lives Matter and the proponents of All Lives Matter felt the pain and sorrow over the deaths of those five officers. Neither group wanted that sort of violence, but once again, black activists must affirm, and affirm again -- this time, that the actions of a man unaffiliated with their peaceful protest do not reflect their message or their movement.

We have a

situation where Black Lives Matter is called to answer

for murders that they did not endorse or commit, while our police

departments do not share this responsibility to answer for the

violence that actually derives from some in their ranks. We all acknowledge that abusive officers exist, but instead of firm rejections of their behavior, there is instead the repetitive insistence that most officers are good. It is granted that not all police officers exploit their authority for unjustified violence, and it is important to be conscious of this, however, that fact alone does not bring accountability to those who do. The acknowledgment that not all officers are bad also implies that not all officers are good. It is a euphemism for which the implication must be identified and addressed.

The abuse that took the lives of two black men this week is either unacknowledged or dismissed. Look at the social media accounts of your friends and public officials who proclaim All Lives Matter. Scroll past their heartfelt words over Dallas, and find their posts from July 5th, when Alton Sterling was shot six times and killed. Then scroll to July 7th, the day after Philando Castile was killed at a traffic stop. Did they grieve for those two men? Did they even say anything at all?

Between these two dates, the presumptive Republican nominee for president made eight posts to his Facebook regarding Hillary Clinton and her emails. That comprised half of his total posts throughout those three days. During this time he said nothing of the police brutality through this medium. This pattern is one that so many maintain, regardless of whether they speak to audiences of dozens or millions.

When a police officer is murdered, we all share the grief, but when a black person is unjustly executed in the streets, we do not. More simply, why does Black Lives Matter receive indignant retorts that All Lives Matter when chanting the phrase Blue Lives Matter does not? By the logic used by critics of the protestors, why is Blue Lives Matter exempt from the same scrutiny over implications of supremacy? That is why it must be said again and again that Black Lives Matter, because until they truly do, All Lives Matter are merely empty words.

We, as white people, must listen. The list of misconceptions regarding the movement we criticize prove that we do not listen. We do not seek to understand or properly assess their situations, thus we are complicit in their oppression. We are barriers toward progress by not responding to the actual intentions and motivations behind Black Lives Matter, but rather to the perceptions of the movement as described by other white people who are separate from those who march for accountability and reform.

We manipulate and seek to control or suppress the discussion that must be had as if it is one that we are too afraid to candidly have. This must stop. It is time to allow those who march for black life to define their movement. It is time for those of color who face the daily realities of racial disparities to be the spokespeople for their cause, not those who sit comfortably behind the cameras of cable television. It is time for us to listen.