The War on Drugs—a military offensive conducted by the U.S. and its allies meant to fight the production, trafficking, and use of illegal drugs—is often lauded as a dismal failure in both policy and planning. While there are certainly those in favor of the traditional prohibition policies that the War on Drugs is based upon, the statistics proving their ineffectiveness are hard to refute.

Authorities in many Latin American countries (alongside the U.S.) have been focusing on the wrong levels of drug trade, violating basic human rights, and undermining the very values they pledged to protect. Furthermore, corruption is rife among those that are hired to fight drug crime, and violent tactics are employed regularly by authorities. While it may seem intuitive to fight violent cartels with violent methods, it in fact has been known to further legitimize and encourage the brutal tactics of the already-notorious drug cartels. When all of these factors come together, they paint a profound picture of the reasoning behind the reputation of the War On Drugs.

Basic human rights and the War on Drugs

The prohibitionist policies sponsored by the U.S. focus on the most ineffectual levels of the drug trade: the working class. While traditional policies regarding the militarization of law enforcement have without a doubt enhanced many countries’ resources to fight drug crime, law enforcement’s capabilities are no longer the issue. Rather, by focusing on low-level and nonviolent crimes, the War on Drugs has only served to spread the underground industry to other countries and divert resources away from the prevention of serious violent crime. These policies have not only proven to be wholly ineffective, but they have also led to a number of human rights abuses that quite frankly would not have occurred otherwise.

In many Latin American countries, sentences of up to 25 years can be given for low-level and nonviolent drug crimes, worsening conditions in often overcrowded prisons. While a significant number of high-level government officials have advocated for human rights, many countries seem to have gone backwards and instead incarcerated even more then they had in the first place. Colombia, for example, incarcerated 6,000 people in the year 2000, but went up to 23,000 people in the year 2014.

Women are also being incarcerated for drug offenses at a much more rapid rate than men are. The reason women are much more likely to be incarcerated is because poor, single mothers often turn to low-level drug dealing or transporting in order to put food on the table. As one can assume, these women pose no harm to society in many instances. Instead, their misfortune is a clear characterization of the misplaced priorities of drug laws in Latin America. Criminals that are often pursued the most by these ineffective policies are also the most easily replaceable. As such, the incarceration of these individuals has little to no effect on the drug trade as a whole.

Latin America is not the only region making leaps in bounds in the detention of low-level criminals; the United States imprisonment rate for drug crimes increased tenfold between 1990 and 2010. About 50 percent of sentenced inmates in federal prison on Sept. 30, 2014 were serving time for drug offenses. However, these frequently incarcerated individuals are often only guilty of low-level crimes and could instead be easily and cheaply rehabilitated, making jail seem all the less appealing.

A study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found that every dollar spent on drug treatment in a community yields over $18 in cost savings related to criminal conviction and detention. Non-prison sentences in place of incarceration also save money and are effective in reducing drug use, the crime associated with it, and prison populations. Luckily, the de-criminalization of many drug sentences in the U.S. is beginning to take hold. These wasteful, ineffective, and unjust policies are being slowly replaced with rehabilitation and treatment in the U.S., and Latin American countries are beginning to do the same.

Corruption and the War on Drugs

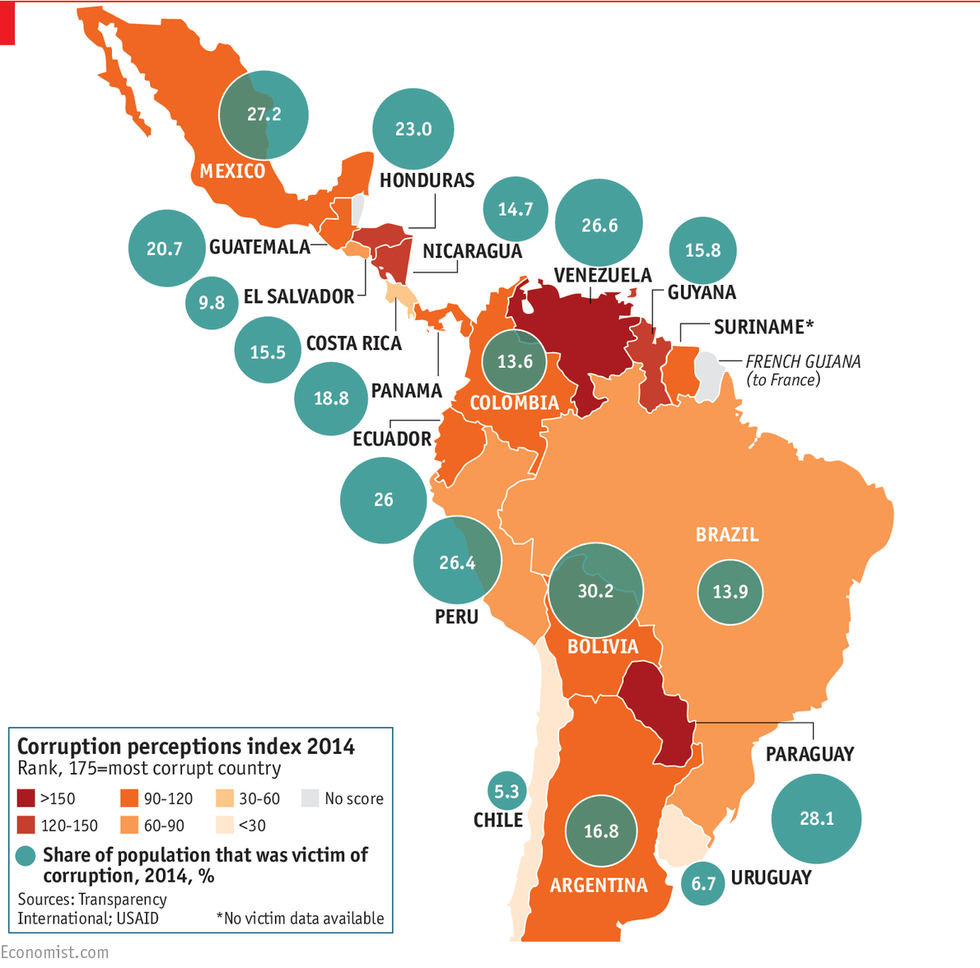

Next to flawed policy, corruption is by far one of the biggest reasons that the War on Drugs has ultimately failed. In Mexico, for example, the ease with which rich drug traffickers can buy off police officers is a travesty. Police in Mexico earn a meager $9,000-10,000 a year, much below the average for public-sector employees. By ‘looking the other way’ during drug trafficking operations, a police officer could easily double or triple his or her salary in one day. Mexico’s judicial system is also known for being susceptible to corruption due to its domineering judges and inherent lack of transparency. Even the higher levels of government are not immune to such debauchery.

On Jan. 15 of 2016, Humberto Moreira, the former governor of the Mexican border state of Coahuila, was arrested on the suspicion of money-laundering and affiliating with a notoriously brutal drug cartel known as Los Zetas. Unfortunately, such a high-profile arrest is not unique; Mexico is well-known to be a hotbed for corruption, as was found in the 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index. Crime must be targeted at a higher level; influential and powerful people involved with the drug trade should be a top priority, not local neighborhood marijuana dealers.

Violence and the War on Drugs

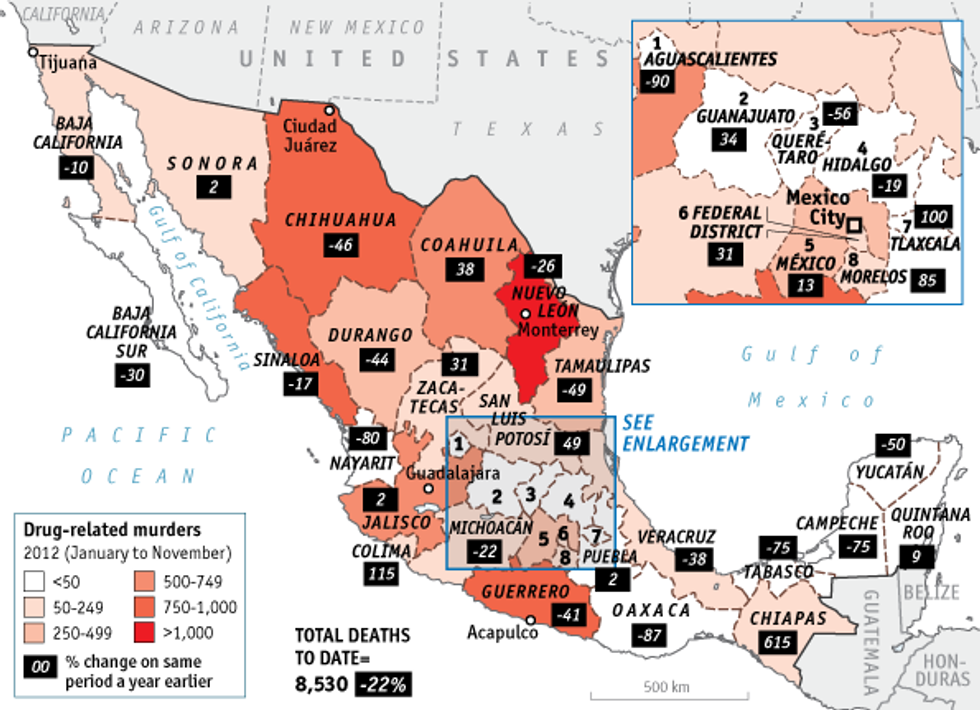

Drug cartels are known to be some of the most violent organizations in the world, and they have profited greatly from their tactics. As much as $30 billion, about 4 percent of Mexico’s total GDP, is made via the drug trade. The criminal organizations also employ at least half a million people, an impressive amount for such clandestine operations. Mexico, after beginning a serious military offensive on cartels in 2006, did little to diminish their presence. Instead, the violence merely splintered a few larger cartels into as many as 80 new drug trafficking groups. These groups fight each other for territory and succession, increasing overall violence exponentially.

On top of criminal-on-criminal violence, more than 100 mayors and former mayors have been killed since 2006, the most recent being Texmico Mayor Gisela Mota. Mota had pledged to challenge local drug gangs, drawing their attention in the worst way. She was beaten and killed in her home just one day after taking office on Jan. 2, 2016. As one can see from the results of Mexico’s military offensive, violence does little to halt violence. In fact, it only makes brutal tactics more prominent and legitimate methods of gaining power.

Due to emotions running high about ‘spillover violence’ and border protection, the U.S. has also decided to make its primary focus border control. Rather than stopping the drug trade at its origins (which is far more effective), it is only stopped halfway through the trafficking process at the border. However, the Woodrow Wilson Center, an institution founded on research and dialogue on global issues, claims that violence is more of a symptom than a cause of the continuation of the War on Drugs.

The Wilson Center states that organized crime and the drug trade is driven by U.S. demand, and the majority of the cartels’ firearms come from the U.S. Therefore, policies must be multinational and cooperative in nature in order to maximize effectiveness. In order to do the most effective work that can be done to prevent drugs from making it into the U.S., policies should focus on preventive measures (i.e. halting drug production and illicit arms dealing) rather than treating the symptoms (i.e. using violence to put an end to violence).

All in all, the War on Drugs, although good-intentioned, has managed to cause more problems for its beneficiaries than ever. Drug crime has only risen in response to violent and aggressive tactics perpetrated by a number of governments, and the majority of arrests made are those who are of little consequence to the ever-expanding cartels. Human rights abuses are reaching record levels, and those low-level members of the drug trade continue to flood overcrowded prisons all across the Americas, wasting money and effort for years on end all for a minor drug crime. Corruption has also all but overwhelmed local governments in Latin America, and those public officials that are not involved with the drug trade are often targeted and killed. Violence has been met with violence, and Latin American society has reached a point where something must change.

Luckily, more governments than ever are pushing for expanded focus on rehabilitation, healthcare, and treatment for those involved with drugs. Meanwhile, legalization of marijuana, the least harmful of the cartels’ products, is underway in a number of countries. While there have been many suggestions on how drug policy should be changed, I believe that the key to cutting the cartels profits is to more effectively convey how harmful drugs are to our societies. While draconian enforcement may make people fear law enforcement, honest and comprehensive education can make people fear the drugs themselves. Societal perceptions and the provision of treatment are definitively cheaper and more effective for those who are low-level offenders. Meanwhile, law enforcement may be able to more actively focus on are the drug lords themselves and their immediate operations.