Coming out is hard. In fact, it is one of the most difficult decisions I’ve ever made. It wasn’t a hard decision just because I was nervous about the reaction of my Catholic father or that I remembered how my someone jokingly called me a “dyke” once. He was very young and didn’t understand what he was saying, but I can still feel the way the word felt on my ears and breath and heart. It was as sharp as knives, robbing my lungs of all oxygen, and for a long time when I heard it, I felt I’d just been bathed in dirt and my own skin felt foreign to me. I was not just fearful that I would not be taken seriously or that I would be seen as a stain on the fabric of my family, but because of a historical precedent that has made it difficult for LGBTQ folks to come out without fear – fear not only of reactions, but for some, of danger. I asked myself for a long time why anyone would come out and place a target on their own back – but during the wee hours of November 9th, 2016, I snapped.

Of the many things that have silenced LGBTQ people from owning their identities and living openly, I cannot think of anything more influential than the anti-gay politics of the Religious Right. The fear-mongering that is used in some Christian communities is not only meant to demonize and devalue queer people as a whole, but it is also meant to suppress and instill terror into the LGBTQ folks in their congregations of ever living in their truths. Ultra-right religious and political leaders have convinced masses of people who love differently than they do that by following and living in their own light, they are no longer eligible to stand in the Light. For every move towards civil rights that the LGBTQ community has made, the Religious Right has rebutted, and believing they have been fired upon, has returned fire in the direction of loving families and partnerships. This is shown in policies like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the “Defense of Marriage Act.” It is shown by organizations like Westboro Baptist Church, who blame events like 9/11 on the existence of homosexuality.

Part of the reason I hadn’t come out until recently was because the laws that protect LGBTQ folks are not consistent or secure, nor have they been throughout time. This is partly because, since the 1970s, the Religious Right has fought the LGBTQ rights movement through reactive opposition – namely, political action, action which has shaped which issues queer activists are permitted to push or which laws and protections we have the time to fight for (Stone). We have been unable to create our own political movement. Everything we do is a response: Religious Right attacks marriage equality, and LGBTQ folks fight once again for the right to marry. Religious Right gets spooked by the reality that transgender people do, in fact, use the restroom, and the LGBTQ community is forced to turn its focus to legislation like HB2, the bill in North Carolina that prohibits transgender folks from using the bathroom that matches their gender and not their assigned sex. The relationship between the Religious Right and the LGBTQ community is part of a movement-countermovement dynamic (Stone). Every time the LGBTQ community turns around, there is someone trying to take something from us. There is always a fight. I was not sure I wanted to fight from the perspective of a visible member of the community. It scared me how greatly history books and political leaders have failed us. Many of the people we have to thank for where we are now are people whose names we will never know.

Another tough part of coming out for me was acknowledging the historical erasure and shaming of bisexuality. Bisexual people are seen as choosy. Many people think we wake up and say, “Today, I’m lesbian” or “Today, I’m straight.” Whereas being lesbian or gay has come, albeit slowly, to be seen as the way one was born, bisexuality still stands, in current culture, to be viewed as a choice comparable to wearing a dress or pants or choosing soup or salad. My identity is not something I “feel like” – it is something I am, something that I bear whether I want to or not, and some days, it is incredibly heavy. This erasure comes even from within our own community. I have met women who have showed interest in me only to find out that they out they don’t date bisexual women. We are perceived as promiscuous or incapable of fidelity. I have been asked, when dating a man, “Oh, so you’re straight?” and when interested in or seeing a woman, I am asked, “So are you, um…lesbian now?” Just to put into perspective the scope of the erasure, I will share here that when I was reading an article from the Journal of Bisexuality in preparation for this essay,the article was filed, by the database, under “homosexuality.” Further, if one flips to the index of a textbook or looks up “bisexual” in the dictionary, they will be instructed thus: see gay.

For all of these reasons, I was fearful. It was 2:30 in the morning on November 9th. I had been up since 6:30 a.m. on the 8th. I woke up and went about my day as normally as I could. I had a cup of coffee. I watched the sun rise. I meditated. I knew that either way, life would be different tomorrow. I promised myself, “No matter what, today, I will not be anxious.” I picked my brother up and we went to the polls. For both of us, this was the first presidential election in which we were eligible to vote. We did it together. The day crept onward. I sat near my laptop, streaming CNN with a bottle of wine and a box of tissues, just in case. I was not sure if the wine and tissues would be for comfort or for celebration. When it became clear that Donald Trump would be the President-elect of the United States, something in me truly did snap. By this time in the evening, I was alone in my room. I could not have anticipated my own reaction to the results. I had a full-blown panic attack in front of my laptop. I smoked ten cigarettes in under an hour. I finished the bottle of wine, and then, I went on Facebook.

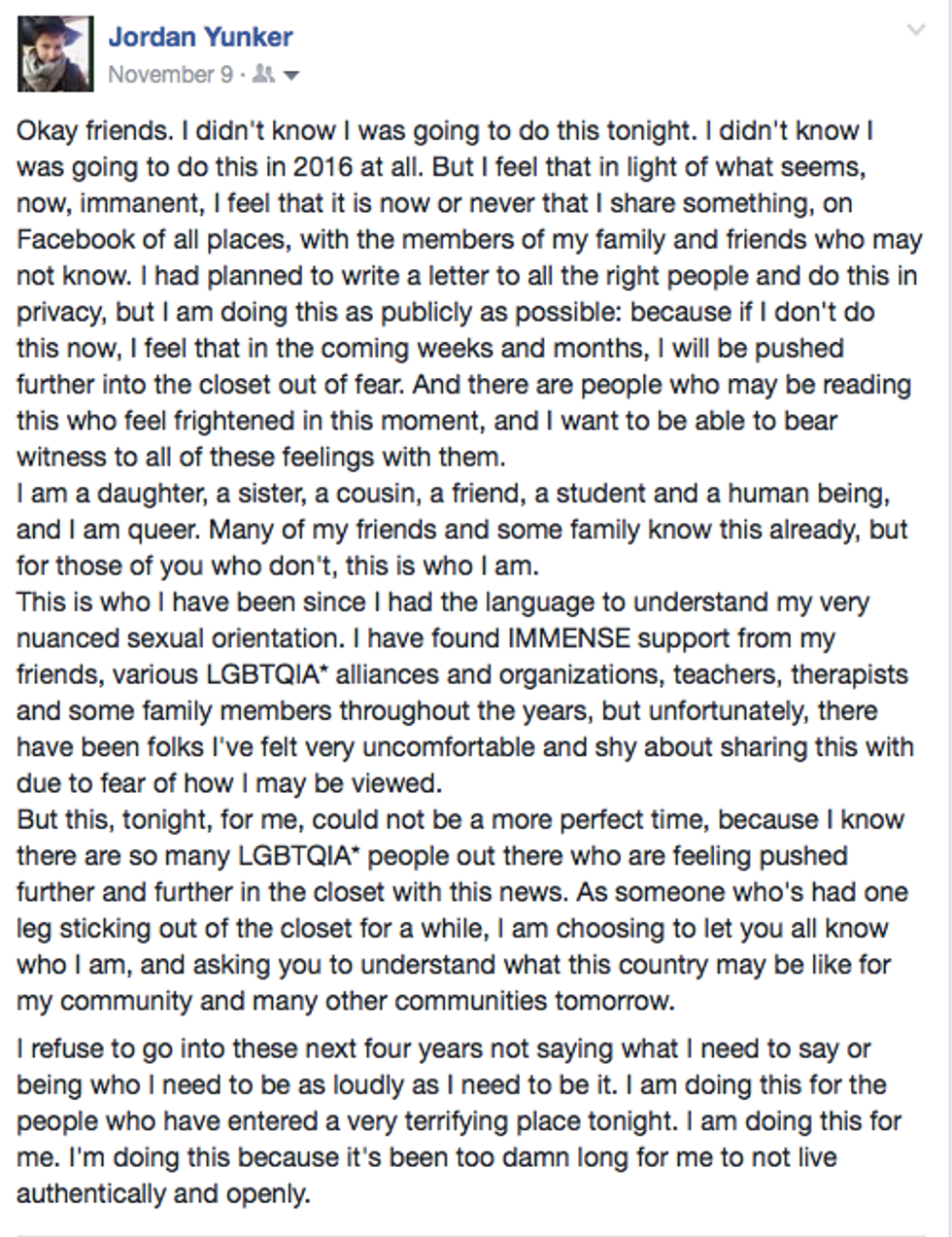

What I saw there, I was not prepared for. LGBTQ friends of mine were speaking of going back into the closet. A post from a young, gay teenager was floating around. It detailed how he felt fearful and at times, suicidal, and how a Trump presidency affirmed that to so many people, he does not matter. My best friend texted me and said, “I am sobbing.” I watched as the collective womanhood of my News Feed sighed in fear, anger, and exhaustion. I saw so many of my queer friends talking about the what-ifs of their marriages, families, and futures. I decided, in that moment, that I would not remain closeted. I could not go on another second knowing that somewhere in this country there were scared kids who needed strong examples – who still need them – and most definitely not when I knew that there was a fifteen-year-old girl inside me who I promised some years ago that I wouldn’t be in the dark forever. Still shaking, I opened Microsoft Word and typed what you see below. It took me twenty minutes to write. I did not edit it. It is my heart and my truth, bared open. I chose to liberate myself in a moment when I felt most trapped.

I came out on Facebook because I needed the moral support of the people in my life who already knew. I think if I would have had to approach face-to-face some of the people whom I found it most difficult to approach, I may have never come out at all. I don’t think it was weak or cowardly to come out the way I did. I think it was strong of myself to know what I needed. It seemed that the whole world was awake at 2:30 a.m. This meant my act of self-liberation had an audience, and even if it sounds selfish to have come out in the midst of a political chaos that continues to affect us all– I so desperately craved the affirmation. I needed to know I wouldn’t be invisible to the people who mattered most anymore.

Some people’s reactions shocked me, for better or for worse. That night did not get much easier. I slept for two hours. I barely made it to my 9:30 a.m. class that Wednesday with puffy eyes and a swollen heart. I made it through the day with the support of a few dear friends and one professor who cared – from whom a hug of solidarity was part of the glue that held me together. On November 9th, I felt seen. I felt visible for the first time since I realized that when I look at a beautiful woman, it is different than it is for most of the girls and women around me.

To me, sexuality was always beside the point. It never mattered to me much that I liked girls. I loved myself for it. It is part of the richness and beauty of my experience. I find myself nodding my head up and down when I read Audre Lorde, the late feminist writer. In her essay, "The Uses of the Erotic," she writes, “And there is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love.” I didn’t know it was a crime to move into that sunlight until someone told me it was. It took a lot of unlearning and a lot of radical self-love to arrive at the point where I am ready to talk about the sunlight, but this is my history and I am here, moving into the light, and it does not make me ineligible to stand in the Light.