Located along 6th Avenue, in-between 6th and 7th Street, this former slave and freeperson's cemetery has become a "Resting Garden."

Dedicated with a historical marker at its main entrance, this historical walking path and rest area is roughly 800 feet in length and has multiple benches and informative markers.

Open 365 days a year, the "Resting Garden" is a wonderful walk and place of contemplation just outside of Columbus' downtown area.

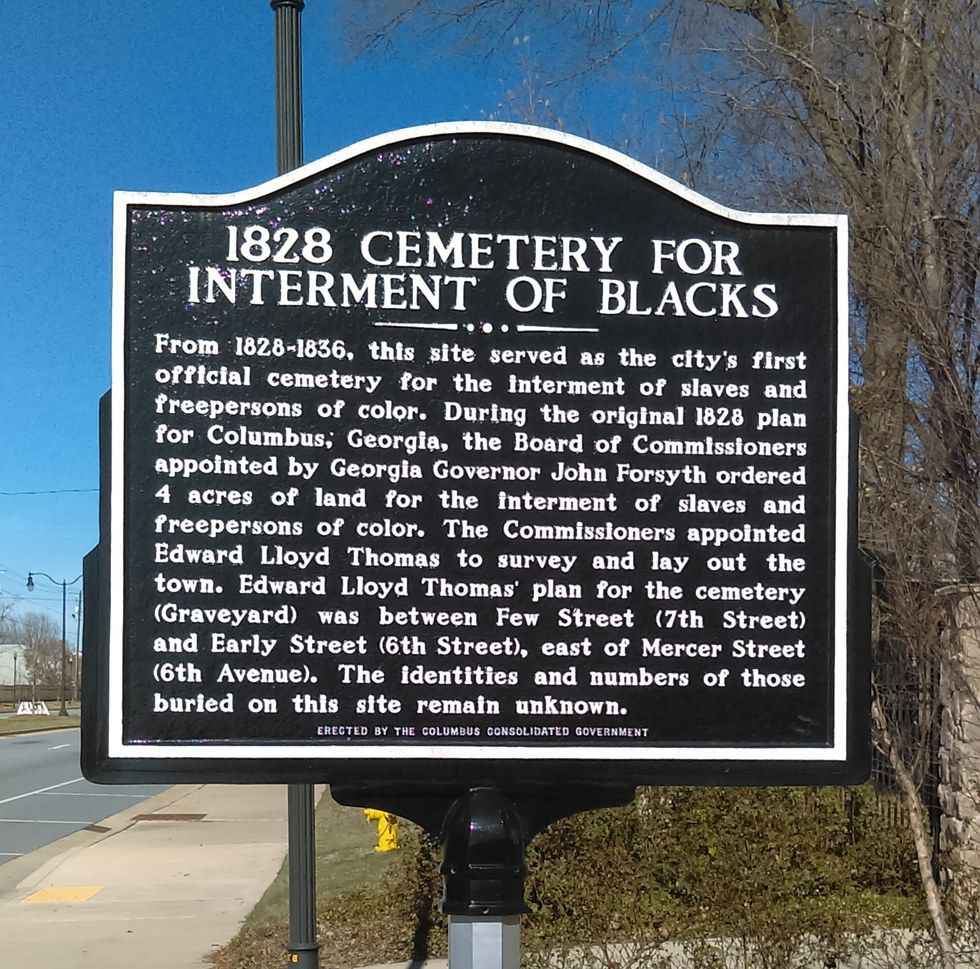

1828 CEMETERY FOR INTERMENT OF BLACKS

From 1828-1836, this site served as the city's first official cemetery for the interment of slaves and freepersons of color. During the original 1828 plan for Columbus, Georgia, the Board of Commissioners appointed by Governor John Forsyth ordered 4 acres of land set aside for the interment of slaves and freepersons of color. The Commissioners appointed Edward Lloyd Thomas to survey and lay out the town. Edward Lloyd Thomas' plan for the cemetery (Graveyard) was between Few Street (7th Street) and Early Street (6th Street), east of Mercer Street (6th Avenue). The identities and number of those buried on this site remain unknown.

Erected by the Columbus Consolidated Government

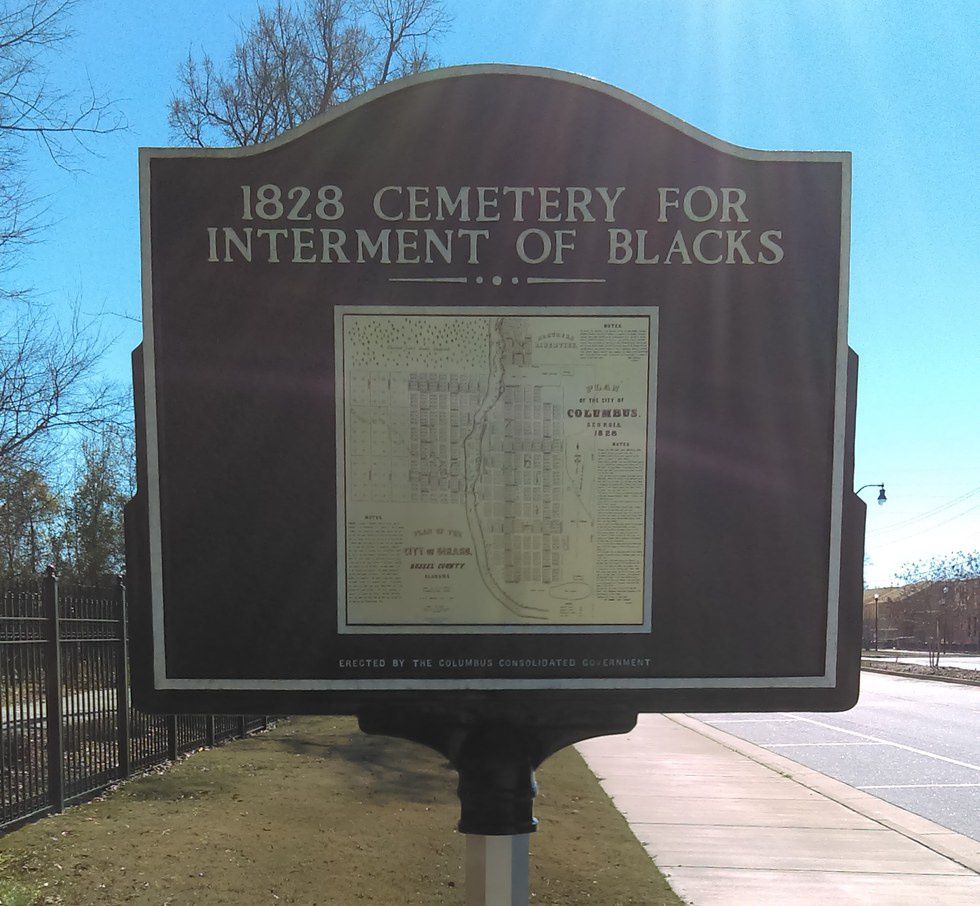

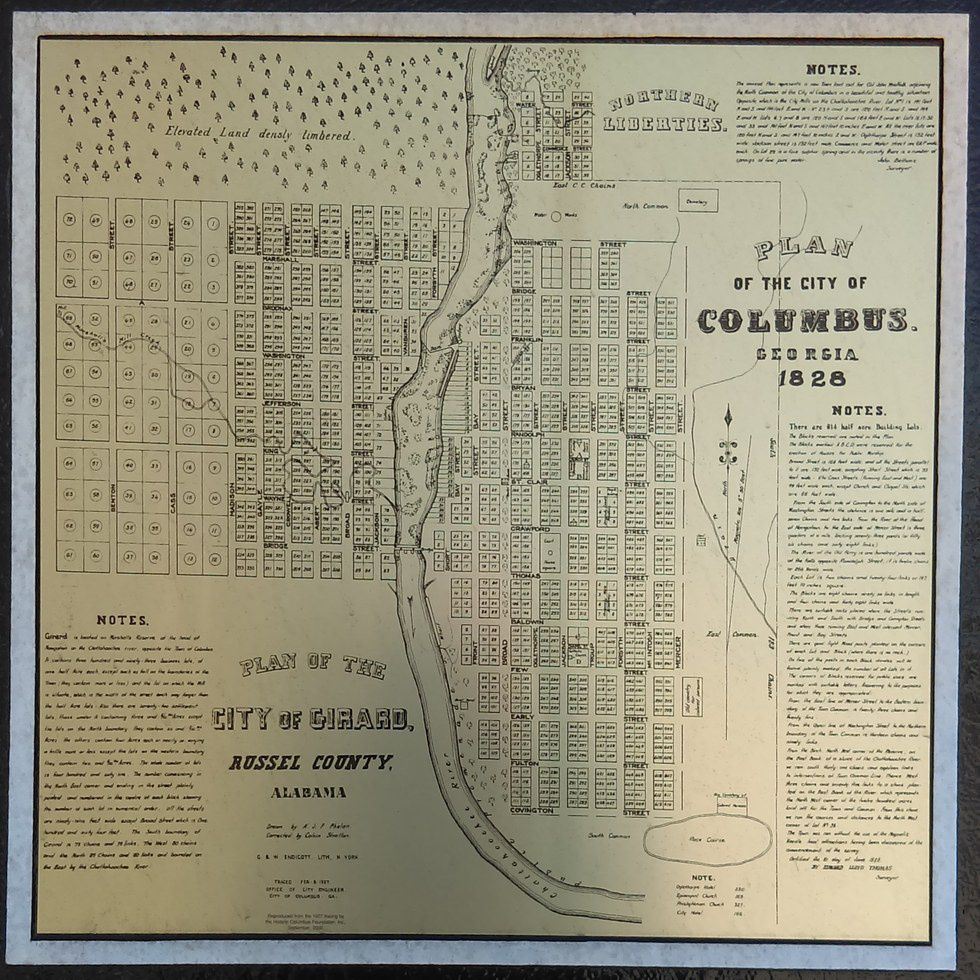

Reverse side depicting Edward Lloyd Thomas' plan of the city of Columbus, Georgia, as well as the city of Girard, Alabama, now Phenix City.

The following are historical markers found along the walking path:

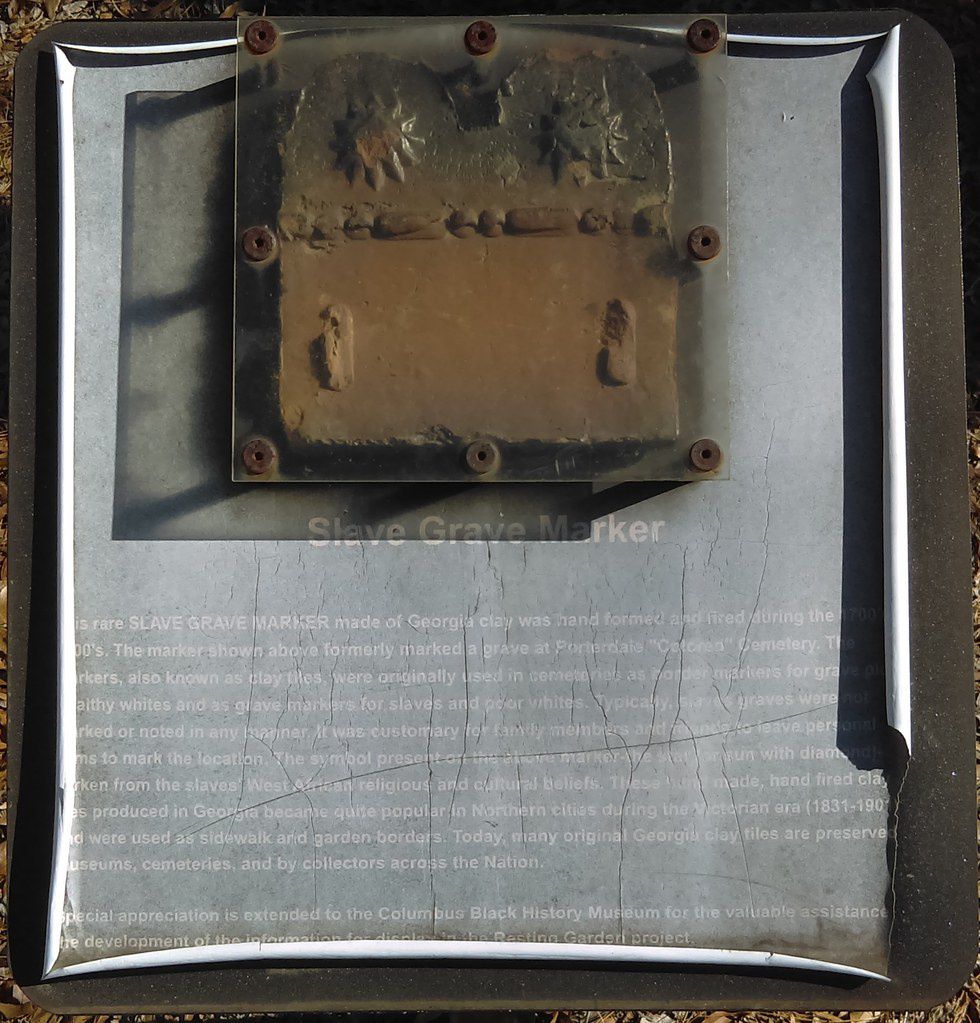

Slave Grave Marker

This rare SLAVE GRAVE MARKER (detail in image below) made of Georgia clay was hand formed and fired during the 1700 to 1800's. The markers shown above formerly marked a grave at Porterdale "Colored" Cemetery. The markers, also known as clay tiles, were originally used in cemeteries as border markers for grave plots of wealthy whites and as grave markers for slaves and poor whites. Typically, slaves graves were not marked or noted in any manner. It was customary for family members and friends to leave personal items to mark the location. The symbol present on the above marker-the star (or sun with diamond)-is taken from the slaves' West African religious and cultural beliefs. These were made and fired clay graves produced in Georgia became quite popular in Northern cities during the Victorian era (1831-1901) and were used as sidewalk and garden borders. Today, many original Georgia clay tiles are preserved in museums, cemeteries, and by collectors across the Nation.

Special appreciation is extended to the Columbus black history museum for the valuable assistance in the development of the information for displaying the resting Garden project

Slave Burial Traditions

The funeral was a critical part of life for enslaved Africans. Slaves demanded to be allowed to give their respects to the dead. The funeral was a place where slaves could come together to acknowledge and celebrate their humanity. Respect for the dead translated into respect for the living. Slaves often insisted that the funerals be held at night. This practice came from West Africa, but it also served a practical purpose on the plantation: at night, slaves from neighboring plantations could sneak away to join in the funeral celebration. Also, the funeral often included a long procession in which all of the people would pass by the grave, shouting, chanting and singing.

Other traditions in the African-American funeral also came from West Africa. Slaves were often buried with their heads facing west. This comes from an old African tradition of facing the same way as the sun is facing when it rises, but it combined with a Christian tradition as well. The slaves read in the Bible that the angel Gabriel would come from the east, and so they wanted to be facing the same direction as Gabriel did when he came at the end of time. Slaves often buried their dead with food, in order to sustain the slave on his trip to the new world. This practice came straight from Africa, as did another unique custom, that of placing broken earthenware on the new grave (depicted in photograph below). The pieces of earthenware were used to symbolize the broken body of the dead slave.

Special appreciation is extended to the Columbus black history museum for the valuable assistance in the development of the information for display in the Resting Garden project.

At the head of Mr. Williams' tomb, located two blocks from the "Resting Garden," is broken earthenware, in regards to the historical marker above.

Religion

Slaves and free persons of color were instrumental in the development and founding of several churches in Columbus, Georgia:

• In December of 1828, the first "Meeting House" for Columbus Methodist worshipers was built. There were 54 white members and 7 free persons of color members;

• On February 14, 1829, the First Baptist Church of Columbus, Georgia was founded by four white men, seven white women, and a slave named Joseph;

• In 1840, the First Baptist Church erected a new house of worship. The old house of worship was given to the local slaves and free persons of color. The church became known as the First African Baptist Church;

• The Saint James African Methodist Episcopal Church was organized in 1863 and ranks as the second oldest church of the denomination in the state of Georgia

• On the bank of the Chattahoochee River under a grape arbor in an oak grove, the Greater Shady Grove Baptist Church was established in 1863 by local slaves and free persons of color.

Special appreciation is extended to the Columbus black history museum for the valuable assistance in the development of the information for display in the Resting Garden project.

Columbus First Black Firefighters

On July 24, 1854, a severe fire occurred threatening the prospering City of Columbus. The fire started near the Palace Mills and the Eagle Factory on the riverfront and spread quickly to surrounding properties. Help was sought from citizens living in the nearby commons. As the fire raged, blacks young and old formed a double line bucket brigade east of Front Street to the River. Using buckets, water gourds, and every available water container they worked unbelievably hard with unwavering exertion and desperate desire in an attempt to prevent the catastrophic fire from spreading. They were promised $200.00 if they saved a house near 9th Street from catching fire. Blacks from the South Commons prevented the fire from spreading and the promise was kept. As the fire raged, white citizens watched from Front Street. Touched emotionally, they would pay tribute to the black citizens at the next city council meeting by making a surprising recommendation that blacks be given their own fire station, equipment, and the ability to elect their officers. City council listened and acted with a positive response. The station at Front and St. Claire and a fire engine was given to them to form the first black volunteer fire company.

Special appreciation is extended to the Columbus black history museum for the valuable assistance in the development of the information for display in the Resting Garden project.

Related article by Ledger-Enquirer writer, Mike Owen, of the opening of the "Resting Garden."