Freddie Gray. Michael Brown. Sam Dubose. Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. Lavon King. Tamir Rice. Eric Garner. We've all heard the names of these black men, and countless more, whose lives were ripped away from them. Not only have we heard their names, but many of us have seen them take their last breaths and heard their haunting last words.

"I don't have a gun. Stop shooting."

Over the years, videos of unarmed black Americans being shot by the police have gone viral in the media. We all remember the grainy photos of lynchings and the black and white photos and videos depicting the police abusing black people. But, to us, that was the past. It wasn't the America we lived in. Those images were decades ago; we lived in an America that had grown past this violence as law enforcement was viewed as the men and women in the television series "Cops." However, the viral videos of police killings have shown us otherwise.

In this new technological age, it is easy to simply pull out your phone, record a video, and post it all in the span of two minutes. The body and dashboard cameras also help to document this abuse, and it becomes more publicly available. These graphic videos gain attention as police brutality is debated on Twitter timelines and Facebook feeds. In some ways, these videos are very helpful, educating the public on the violence against black people by law enforcement that has been prevalent for decades. They have helped start civic protests and gained media attention. They provide a shock value and forces the public to have a conversation on this epidemic. But, they haven't slowed down the rates of these killings or made officers more accountable. The video is posted, there is outrage, a cop's "punishment" is paid suspension, and the cycle starts back over again.

After years of seeing similar videos of unarmed black citizens having their lives unjustly taken away, one starts to become numb to this violence. The constant exposure desensitizes viewers and can cause trauma. Young black kids are seeing people who look like them being murdered by a force that's supposed to protect them. They watch the deaths again and again, hearing the victims' last words begging for their lives or questioning what warranted this violence against them. This increases their fear that they, or someone they know, could possibly be the next hashtag.

My parents have taught me how to act when I'm pulled over. "No sudden movements. Always tell their officer exactly what you're gonna do before you do it. Don't reach for your registration too abruptly, you could scare them." Whenever I'm pulled over, I hold my breath scared that one wrong word or one wrong move could turn a situation violent. That I could become another hashtag, people arguing over my death before another hashtag is made. When my brother or father gets pulled over I'm terrified for them, too.

When videos of black death are being played on a loop and often times becomes unavoidable, the videos lose their shock value. Viewers have seen the same scenario played out with different people, so they become numb to this violence. The family members of the victims are surrounded by the footage of these senseless killings. It somehow becomes almost normal. In 2015 when news reporters Alison Parker and Adam Ward were killed on television, the media decided the video was too graphic and violent to be shown. So, what separates them from the black Americans whose last moments are broadcasted on every outlet?

So the question is, how should these videos be handled?

The individuals courageously record the violence as evidence, however, it's been proved time and time again that this evidence rarely gives the officers the consequences they deserve. The conversation that sparks on social media is often inspiring but doesn't last long. Sharing these videos won't change anyone's mind. It will only further prove what someone already believes, or there will be an argument over if the victim deserved to have their life taken.

However, it's seemingly impossible to stop these videos from spreading on social media, but it should also become a responsibility for news outlets to censor these graphic videos. The trauma that is experienced is unavoidable and another side effect of the racism black Americans face. We keep recording and sharing these videos and traumatizing ourselves again hoping the videos will inspire real reform. How many more videos need to be posted? How many more hashtags need to be made? How many more lives have to be taken before our justice system and government take action? We can only hope that one day these videos will truly make a change.

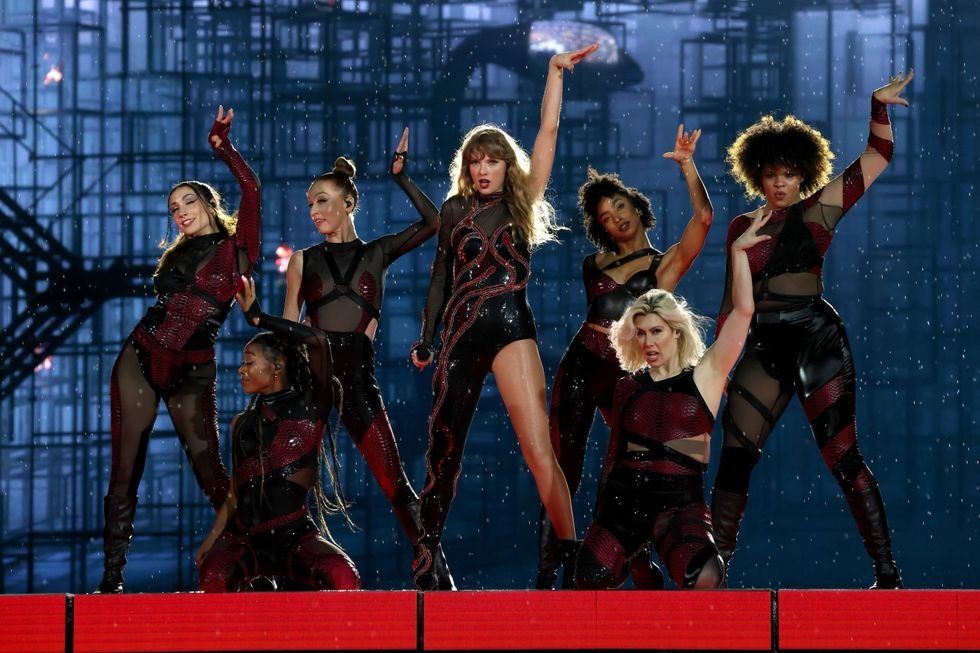

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.