One of the most important tools a game developer can use to engage the player is choice. In other media (cinema, literature, graphic narrative, etc.), the viewing party is relegated to a passive role, unable to personally engage in the issues presented. In video games, the thematic questions posed are often thrust into the hands of the player.

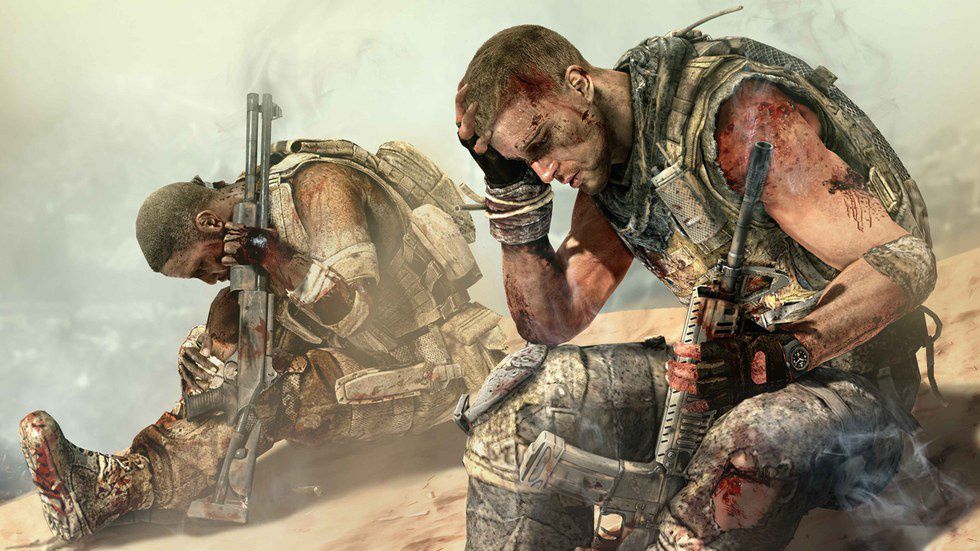

Enter Yager Development’s 2012 shooter, Spec Ops: The Line.

Now with 80% more moral dilemma!

The game follows a team of Delta Force operatives as they initially embark on a rescue mission to the recently devastated city of Dubai. Very quickly, things turn south, and the operation goes form bad to worse to nothing shy of utter disaster.

Based on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (and, by extension, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness), the game’s narrative is a far cry from the lighthearted affairs of Super Mario or Banjo and Kazooie. The game confronts a number of gruesome topics, including but not limited to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), war crimes, and the grey morality of warfare.

I’d make a joke here, but there’s nothing really funny about any of those.

What I really want to call attention to here is the game’s use of “binary” moral choices. You see, despite technological professions made over the last decade or so of narrative games, most moral choices are still presented a simple “good” or “evil” decisions. Even critically acclaimed games, like Bioshock or inFamous, fall into this trap. Yet, in not framing its choices in a clear moral light, Spec Ops forces the player to really consider the consequences of his/her actions.

Speaking of which…

The best way to illustrate this might be an example from the game itself. Be warned – we’re venturing into spoiler territory here; it’s nothing major but consider yourself warned.

About of a third of the way through the game, Walker and his squad come across two men being dangled from a bridge. Through radio broadcast from the game’s antagonist, we learn one of these men was a civilian who stole water rations (effectively dooming several other families); the other man was a soldier who murdered an innocent family as retaliation for the theft. The antagonist’s forces are encamped in the area; Walker must choose who to kill before the game may progress.

There’s no clear right or wrong choice here; both men being hung from the bridge are responsible for the loss of human life. As Walker, the player must make a choice as to which crime is more offensive, and the game reacts accordingly. Of course, the player needn’t make a binary choice at all; it’s a perfectly valid course of action to engage the soldiers placed by the game’s antagonist. This action will result in a firefight, and both hanging men will almost certainly die.

Thus, as the player, we must ask ourselves, which is right? Is there even a right choice? In war, what determines what is "right" or "wrong," "good" or "evil?" How should we, as the complicit party in this act, react?

Cheery.

But, again, the game doesn’t make any course of action more “morally right” than another, and in the end, Walker (and by extension, the player) is responsible for every action taken in-game. In the hopes of not spoiling the game’s big twist, I’ll simply say there’s an especially horrifying choice the player must make regarding white phosphorus.

These choices only have significance because they are presented even-handedly to the player. They are not predetermined by existing text or linear film composition, and though their consequences are limited within the scope of the game’s narrative, the keep the player on-edge, constantly reevaluating the choice they make within the game’s narrative. Spec Ops: The Line is brutal, but the game never forces you to make a choice, let alone a clear “good” or “evil” choice; if you play the game, you accept the responsibility for your actions. Period.