On Monday, February 6, I went to the Chittenden County Police Station to fill out paperwork just as every other elementary education major at my school has done; I, however, had an experience that I’m sure many of the other students at my school have not.

As per usual procedure, the officer that was helping me needed to input my information into the computerized system: name, address, birth date and place, SSN, eye color, hair color etc. Finally he got to the drop down menu labeled “race,” causing him to look to me with a questioning expression.

At this point, the officer already had an idea of my identity having seen me and being told that I was born in Puerto Rico. He turned to me and bluntly said, “Here are your options: white, black, Asian, Native-American and Unknown.” I wasn’t sure what to say. I was confused and frustrated. I knew it wasn’t the officer's fault, but in that moment he was asking me to make a choice I felt I couldn’t make.

Each answer ran through my mind: I look white, so maybe I can say I’m white? But I don’t really look white, I only have fair skin, one look at my other features — the texture of my hair and shape of my nose in particular — and any white woman would raise her eyebrows at me knowing I didn’t belong to the same racial group as her. With my complexion, I couldn’t imagine putting black as my race, even though thinking back to my grandfather and the stark darkness of his skin, I could likely make the argument for myself. Asian seemed the furthest from me, although it would be cool if it wasn’t, and I just felt much too far-removed from my original heritage as Taino Indian to call myself Native.

Before I walked into the sheriff station that morning, I surely thought I knew where I was from and how to (more or less) account for my heritage, but at that moment I felt that “Unknown” was likely the best answer, considering how lost I was in all this.

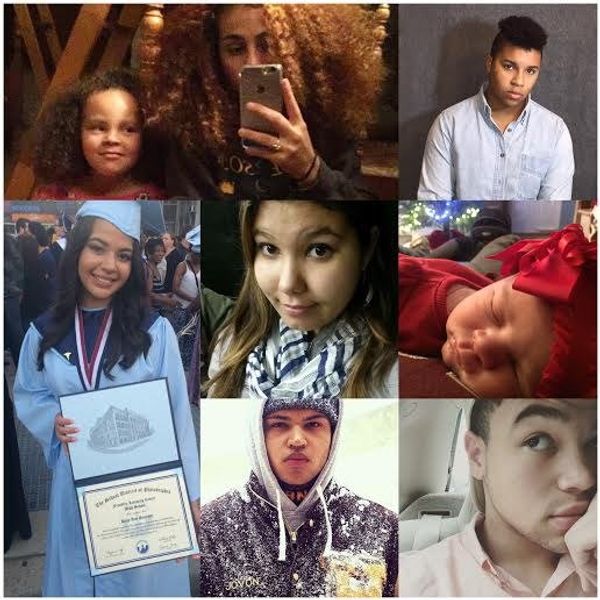

Growing up, I had always learned that Puerto Ricans — like all other Hispanics/Latinos — were a mix of all things. You see, it’s not an easy guess with us: if you’re born in Arecibo (and of course depending on your parents), you might come out as light as me and be seen as “white passing,” or you might be born in Loíza and look as dark as my grandfather and live your life being labeled as “black.” Add that together with your family's heritage and you might have “Asian-looking” eyes like my sister and grandmother and you may very well come from Native descent.

I understand that, currently, there is a debate circulating about whether Hispanic/Latino can be considered a race considering that we look like a mix of everyone else. But those who say that must consider that to be Latino is a mix of a race, ethnicity and nationality. It is a way of life and to say that we are simply “black” or “white” is to strip us of the identities we’ve worked so hard to be respected for.

You don’t need to agree with me, but know this:

Growing up, when I went to predominantly black schools, I was “the white girl” and I was treated as different for it. I was passed around for my classmates to braid my hair because I had “that good, white hair.” Children would squeeze or hit my arms to see them change color from a paler white to pink, and then back to my original color. They thought it was cool and strange how my skin could change like that.

Continuing onto predominantly white schools, people ask me where I’m from and what it’s like there. They call Puerto Rico a Third World country and don’t believe me when I say I’m American just like them until I show them sources to prove it. The closing line usually ending with, “Oh, but it’s different, though.”

I imagine that when reading this, many will shrug and attribute my frustration to the police system or to teen sensitivity; but it is a systematic struggle for all those who identify like me. You don’t have to care but I beg you, even dare you, to consider how this would affect you if the same thing happened to you.

Consider for a second of your day how you would feel if the police/sheriff — the very institution that is supposed to promote the comfort, safety and protection of the people — suddenly erased your identity and gave you the label of “Unknown” as consolation for it all.

Consider how you might feel if you were you constantly reminded that you don’t quite fit into the societal system like everyone else.

Consider how you might feel if, instead of everything being made to include you, you were shown that your identity didn’t matter.

Consider living “Unknown.”