In the previous article, we covered the beginning of the Cold War and the events contributing to the start of the Korean War. In this article, we will cover United States involvement in the Korean War and how it influenced the American government's foreign policy in the Cold War and the consequences to their domestic politics.

U.S.-U.N. Response to the Korean Conflict

When the North Koreans invaded the South, the international community was shocked, and the United States, which had only recently ended its occupation in the region, could not offer an immediate response. President Truman went before the United Nations, asking for aid in the conflict. On June 27, he ordered the American military into South Korea, backed by the United Nations. This would mark the first time a sitting president used the military without a formal declaration of war by the Congress, sparking constitutional debates over the issue continuing into the present day.

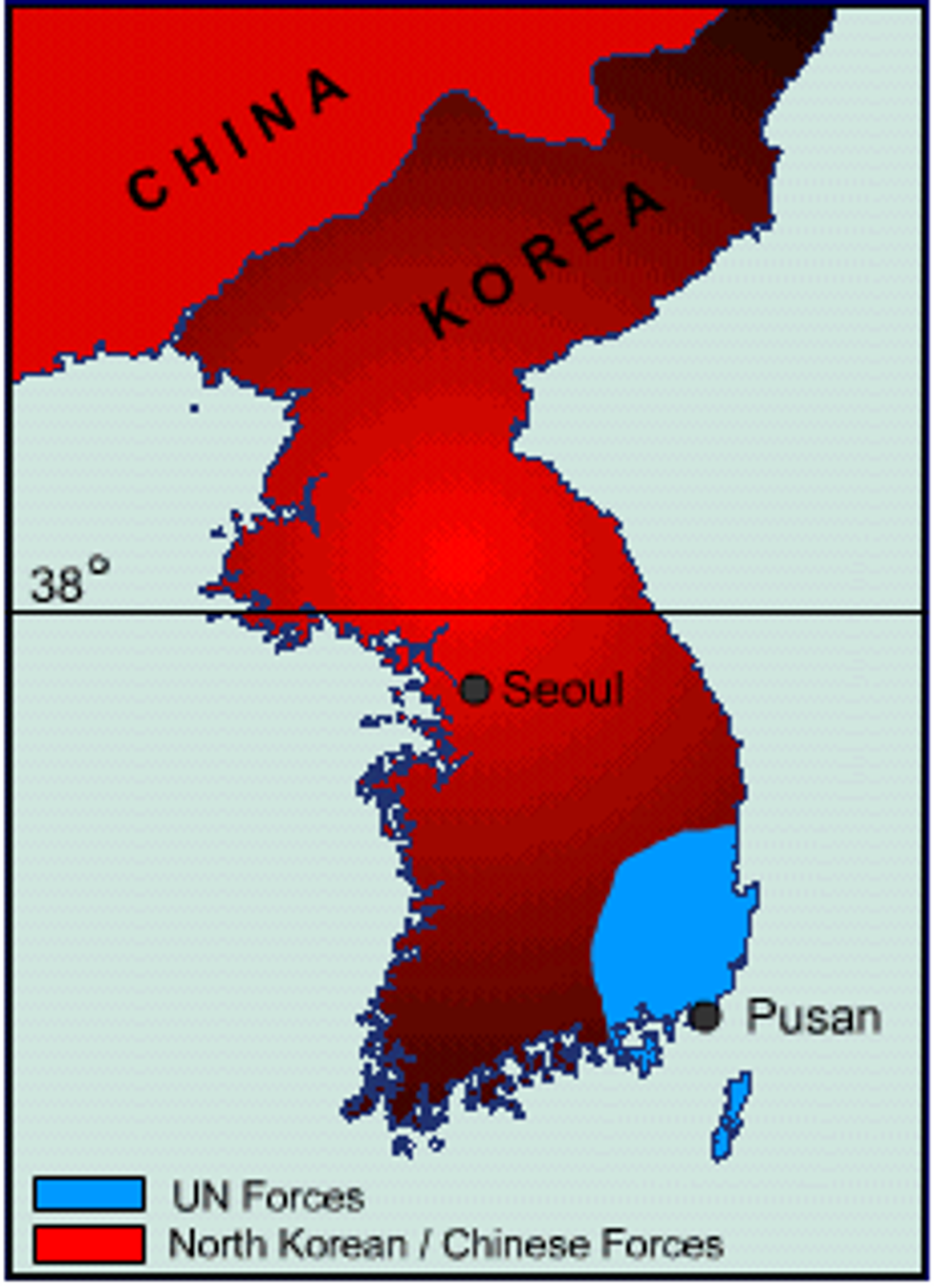

However, neither the United States nor the United Nations were prepared to defend Korea, and although U.N. forces arrived on July 4 to resist the Communists, his troops were pushed to Pusan at the furthest end of the Korean Peninsula. By September 1950, with the Americans still pinned at Pusan, it seemed like the North Koreans had won the war for the Communist unification of Korea.

MacArthur Turns the Tide, September-November 1950

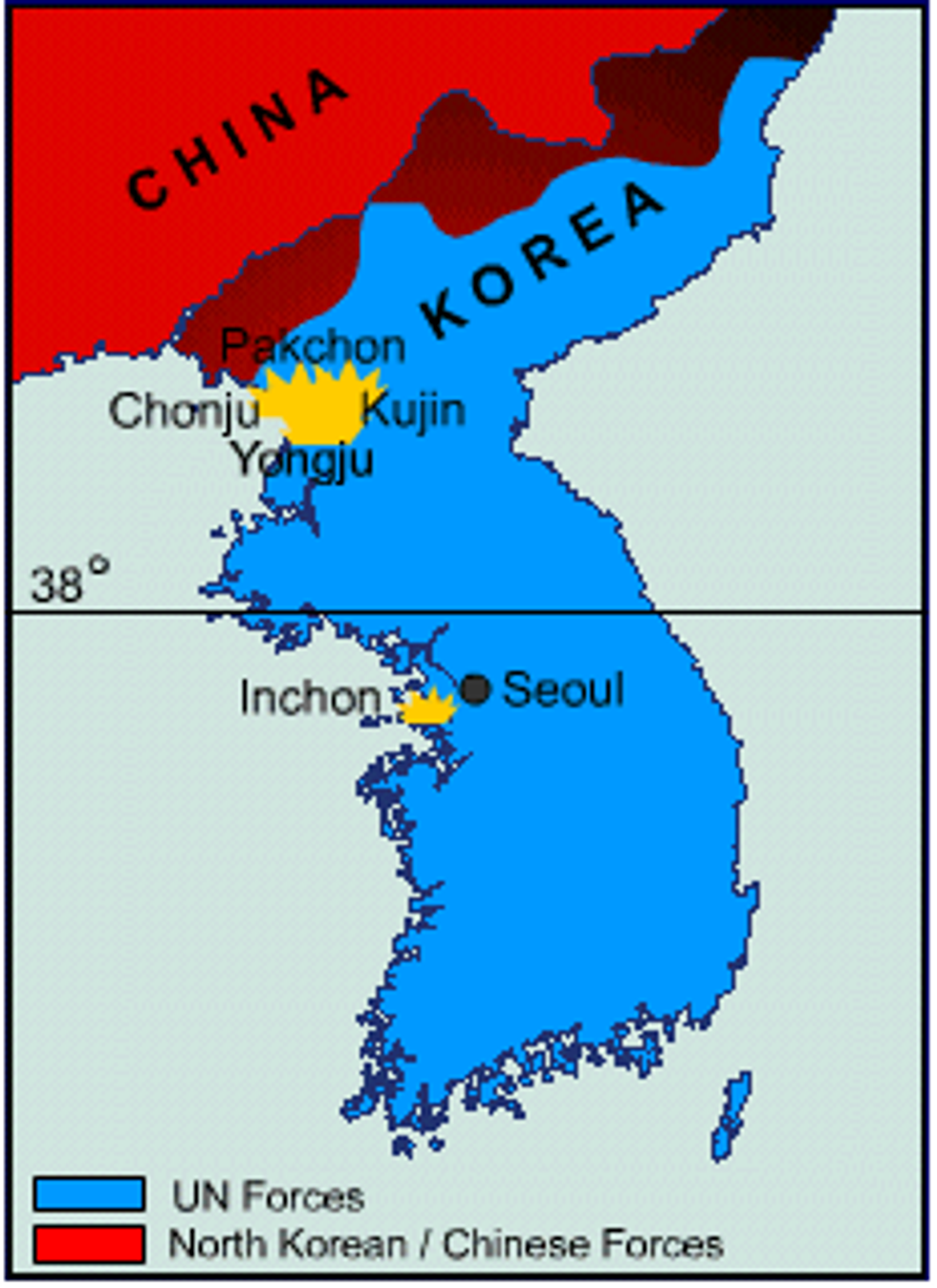

The North did not win, however. Though they had pushed the U.S.-U.N. army to Pusan, the Communists could not push him out of Korea entirely. Commanding officer Douglas MacArthur ordered the field troops to end the retreat at Naktong River surrounding the Pusan region, and they held their own at the South Korean coastline. This coastline defense proved advantageous, as U.S.-U.N. joint forces were able to pour into Pusan to provide MacArthur with much needed men and equipment. Launching a counterattack in September, the U.S.-U.N. forces began reconquering their lost territory. By September 19, a 40,000-man U.S.-U.N. force beat the North Koreans in an amphibious assault on Inchon near the 38th parallel. By October, MacArthur's troops reached the 38th parallel; crossing it, they reached the Chinese border. Victory was seemingly achieved, and from October to November, the United Nations initiated a plan for the official unification of Korea.

Ongoing War and Stalemate, 1951-1953

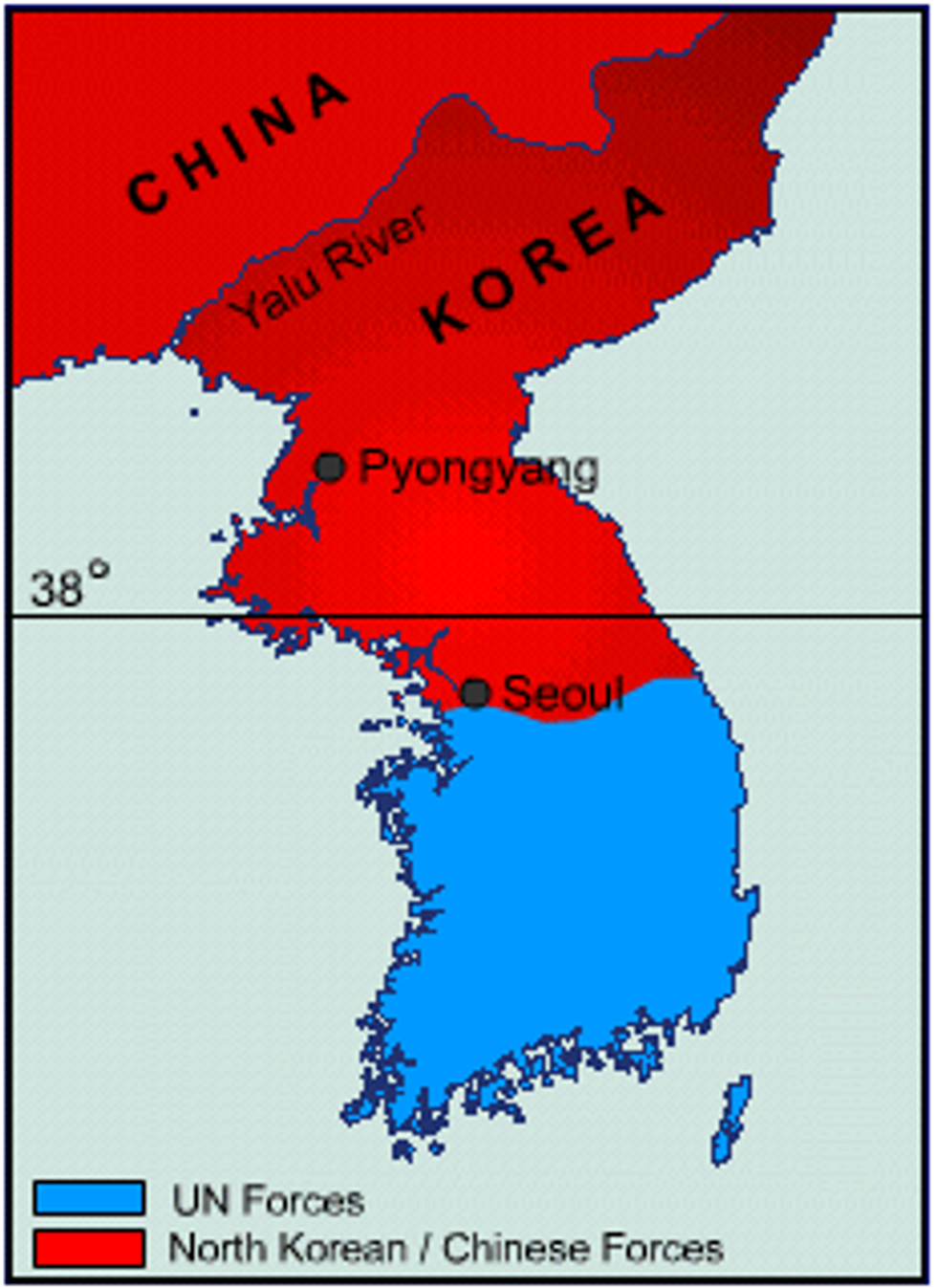

The war, however, was not won. When MacArthur's force reached the Yalu River at the Chinese-Korean border, it did not expect the subsequent Chinese pushback, having been assured from MacArthur himself that the Chinese were no threat. After news was broadcasted of the U.S.-U.N victory at Inchon, the Chinese mobilized at the Yalu River. 1,200,000 men under General Peng Dehuai sent MacArthur's army reeling backwards, and the South Korean capital was again captured by the Communists on January 4, 1951. The Soviet Union, which had been supplying military equipment, now supplied the North Koreans in earnest, and with the backing of Stalin and China, they kept the pressure on MacArthur's troops.

In the United States, the war was becoming increasing unpopular with the public. It was only a back-and-forth between the militaries of the U.S.-U.N. and the North Korean Communists. Territory gained yesterday was territory lost today. Angered families demanded that President Truman pull out of Korea, bringing their sons, fathers, and husbands back home. Truman began to reverse his plan for victory in Korea, and refused MacArthur's request to take Chinese bases near the Yalu River. The general was defiant, believing the president was essentially caving to the communists. After MacArthur publicly defied Truman, the latter angrily relieved him of command, appointing Matthew Ridgway in his place. Ridgway's appointment did little to change the tide of the war, with back-and-forth territorial gains between the U.S.-U.N. and the Communists continuing for two years.

Despite the public's discontent, Truman, did not want to end the war by losing to the Communists, who would see such a loss as a sign of weakness in their opponent. A hopeful Stalin continued to support the North Koreans, so Truman did not pull out. However, he could not put up with the public dissatisfaction for long, so he had Ridgway focus only on holding South Korea as things had been in prior to the start of the war.

The tide finally changed when Stalin died in March 1953. The Soviet government, now faced with choosing Stalin's successor, could no longer focus on North Korea and ended support. The threat of the Soviets removed, the United States was finally able to end the war. In July 1953, negotiations between the United States, the United Nations, China, and the two Koreas began, establishing a Demilitarized Zone dividing Korea in half, though both, even today, have troops along their borders.

Conclusion

The Korean War tested the American resolve in the Cold War against the Soviet Union, and after it ended, many in the Free World felt that the Americans hadn't really beaten the Communists. The Truman Doctrine's policy of containment had worked, but only barely; indeed, American historians today suggest that the Korean War spelled failure for the United States in the Vietnam War in the 1960s. At the same time, the war solidified containment as the United States's response to any Soviet activity during the Cold War, a policy that was finally broken in 1981 with President Ronald Reagan's pledge to end the Cold War by eradicating international communism.

For the Koreans, hostilities between the North Korean Communists and the South Koreans continue to this day, with some mild conflict still harming soldiers and civilians alike.

The Korean War also marked the United States as the leader of the Free World. Despite involvement in the two world wars, the United States attempted to keep out of the international scene. The beginning of the Cold War changed this, as threats of Communist expansion and Europe's inability to respond prompted U.S. intervention. The Korean War cemented their new role as the "first responders" in foreign disputes.

Domestically, the military powers of the American President grew. Per the requirements laid out in Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 and Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution, the U.S. Armed Forces can only be called into duty with a congressional declaration of war. President Truman never sought the approval of Congress. Ever after his successors have used the military without congressional authorization, sparking constitutional debates over the issue that continue to the present day. Domestically and internationally, the United States's involvement in the Korean War has proved more consequential to modern day politics than any other U.S. entanglement in world affairs.