Over my four years in college, I have attended 4 different schools. I spent my freshmen year at the University of Kentucky. For my sophomore year, I transferred back home and spent two years at Southwestern Illinois College. During my second year at SWIC, I applied for dual enrollment at Southern Illinois University - Edwardsville. Currently, I find myself at a small, faith-based liberal arts university in Vienna, WV, called Ohio Valley University.

Over the course of those four years, I suffered a strained ACL in my left leg, a concussion, and, most recently, an inflamed rotator cuff and UCL strain in my right arm. All of these injuries are sports related. None of them, however, resulted from a sport sanctioned by the NCAA.

These injuries all came at the hands of the fringe activity known simply as ultimate.

For those unfamiliar with the sport (or who associate the flying disc activity with drugged up hippies on the quad), ultimate is a high action, spirit-oriented sport characterized by full field throws (in excess of 70 yards), big posterizing jumps, and incredible layout catches on par with some of the best outfield plays in Major League Baseball. Its primary draws are the core beliefs of Spirit of the Game, affordability, and low risk of injury to those who play.

But those who play will tell you that injuries are regular and some can be extraordinarily gruesome. And those who play at and cover the upper echelons of the sport will tell you that the physical impact of ultimate on the human body is not understood through rigorous study, but through analogous comparison to other activities such as football, basketball, and soccer.

Plays such as this layout by Jacksonville's Andrew Carleton can result in serious injury. The affected Atlanta receiver, Sean Sears, was later diagnosed with a concussion from the hit.

Contested jumps downfield can lead to players coming down at an awkward angle, kcausing tears in the knee and other disturbing injuries which require serious surgery and physical therapy. This incident of former Indianapolis Alley Cat and internet sensation, Brodie Smith, resulted in a torn meniscus.

The lack of awareness in regards to injury and health of ultimate players poses a major issue for not only the advancement of the sport, but the establishment of its legitimacy. Ultimate has grown in recent years, with USA Ultimate (the national governing body of the sport in the United States) membership increasing to 53,362 registered members in 2015 (approx. 18,000 were college students), the establishment of the semi-professional American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL) in 2012, and the recognition of the sport's international governing body, the WFDF, by the International Olympic Committee in August of 2015.

But the biomechanics, exercise physiology, and overall understanding of injuries sustained in ultimate are all limited to a single statistical research paper published by a team at the School of Public Health at Harvard University in November 2014. The full paper, found here, analyzes the epidemiology and sets out to define the, "diagnoses, anatomical locations, and mechanisms of injuries," of college ultimate players in the US during the 2012 season. In other words, the researchers' sole purpose was to analyze how injuries happened and how often, but not how to prevent them or treat them.

The study was made up of 53 women's and 53 men's teams from across the United States. Unfortunately, the survey failed to define injury diagnosis due to inadequate medical staff for participating teams. Instead, the injuries were defined as injury determinations and the incidence of an individual injury was not universally recognized. For some teams, only the most serious fractures and ligament damage were counted while other teams included cuts and abrasions from an errant disc. The study also sought to record each injury based on anatomical location, injury type, how the injury occurred, and whether the incident occurred in practice or in game. The paper also measured the incidence rate (IR) as injuries per athlete-exposure (AE), with one AE being one player participating in one practice or game. Total AE for the study was 104,193.

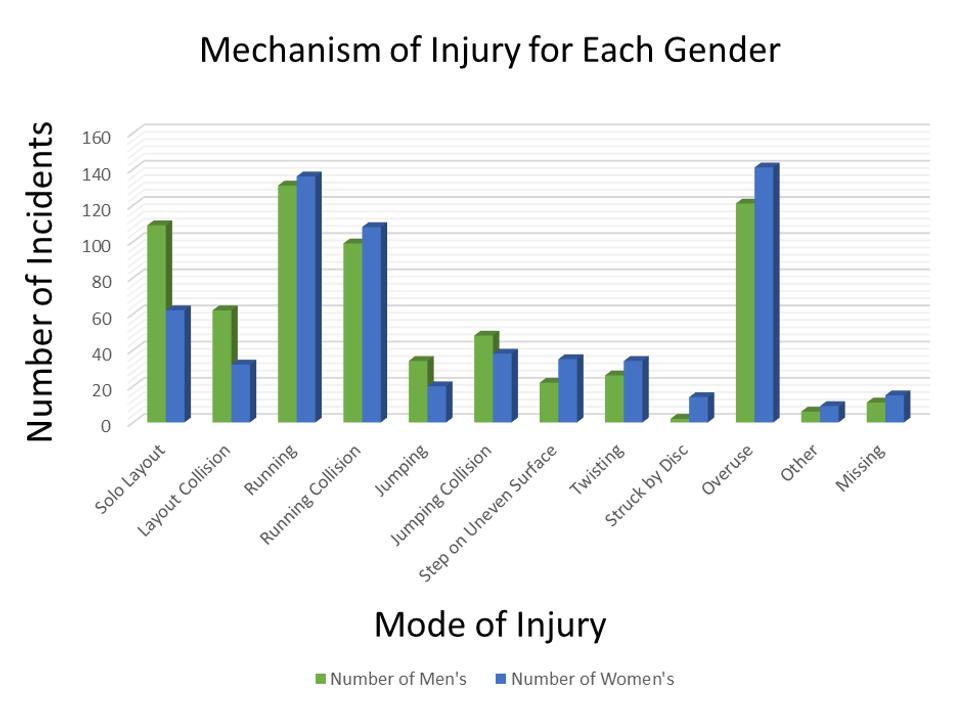

Ultimately, the paper determined that the, "Injury patterns to college ultimate players were similar to those for athletes in other National Collegiate Athletic Association sports," implying that ultimate players were just as likely to sustain injury in the same fashion and anatomical region as athletes in other NCAA sports. 1,317 injuries were recorded across the 104,193 AE's, for an IR of 12.64 per 1000 AE. There were no significant differences between the injury rates of men and women athletes, though the severity of injury in certain regions differed significantly. Men suffered more injuries to the upper body (primarily dislocated shoulders sustained through body-ground or body-body impacts) while women were seven times more likely to tear a ligament in the knee. Overall, strains, sprains, and tears of muscles, tendons, and ligaments were the leading cause of injury, with 582 total incidents. The overall breakdown of injury mode and number of incidents per mode per gender is found below.

The primary culprits of injury in the sport are running related. The act of running on inadequately prepared muscle/ligament systems leads to sprains, hyperextension, or tearing of vital musculotendon groups in the ankles, calves, knees, and thighs. Collisions with other players while running can result in concussions, fractures in the arms, chest, and head, dislocated shoulders, and torn ligaments in the upper extremities.

As mentioned previously, this study was limited in its scope by one major factor: lack of trained medical staff or athletic trainers. This is a major issue considering the study compared the incidence rate to that of major NCAA sports and a sizeable number of training regimens, stretching programs, and injury treatments utilized in ultimate are geared for sports which only share parts of their kinesiology with ultimate. The explosive nature of football. The endurance and offensive patterns of soccer. The vertical intensity of basketball. The shoulder and elbow strain of baseball. With all of these factors being key facets of the sport, where are the in-depth studies? Furthermore, with consistent injuries to players over the history of the sport, where are the medical professionals who typically train athletes to avoid these injuries in the first place?

Both of these questions hung around for a considerable time after I strained my UCL in October of 2016. Consistent use without adequate resting and a lack of preventative care which took into account the intense distances and speeds which discs are thrown by players led to inflamation and tightening of the tendon which resulted in significant pain and damage in the right elbow. Thankfully, ready access to the training staff at my university helped me to isolate the problem and adjust my mechanics to alleviate stress to the joint. But such luxuries are not afforded to many teams, especially at the critical developmental stage most players find themselves in during college.

Over the course of the Spring 2017 semester, I conducted a small, albeit imperfect, survey to gain a rough understanding of the access teams at various competitive and divisional levels have to certified athletic trainers. The survey garnered a total of 187 responses from teams across all divisions, competitive levels, and regions in USAU, in addition to responses from two former AUDL players. The results were as follows:

- Of the 187 surveyed teams, only 50 have regular, ready access to a trained/qualified medical trainer with a specialization in sports medicine.

- Of the 54 college teams in the survey, only 9 teams have ready access to a trained/qualified medical trainer with a specialization in sports medicine.

- Of the 33 high school teams in the survey, none of them have an on-staff athletic trainer in the event of on-field injuries.

- Along the gender divisions, 17% (17) of open teams, 37.5% (12) of women's teams, and 35.6% (21) of mixed teams have access to trained medical staff. However, approximately 85% (43 teams) were reliant on a team member with medical experience as opposed to dedicated trainers.

What was most surprising through this process, though, was the lack of care and attention to detail when communicating injuries and severity. Of the 187 survey entries, all but 3 reported an injury which prevented the affected player from full practice/game participation for a period in excess of six weeks. Of the 184 which reported at least one significant injury, only 57 (that's 30.98%) went in depth as to the exact location, incident, and severity of the injury. Of those 57, only 38 reported a visit to a sports medicine doctor to evaluate the injury and set a treatment plan for the athlete.

Almost as if to add insult to injury, the plays which result in these types of injury are largely illegal per USAU rules of play, and the players who commit these errors are typically the ones who receive the screen time from ESPN and other mainstream broadcasting groups which spread the sport to the mass public. This creates a whole different issue involving the sport's representation and mainstream following which has already been covered numerous times by outlets such as Ultiworld and Skyd Magazine.

But moving forward, what could be done to fix what is a fundamental problem with the culture of the sport? There are three key areas I feel need to be further studied.

First is preventative care and maintenance of body systems. Proper education of ultimate teams at the youth, high school, and college levels in regards to the sport is critical. I would propose a focus on flexibility of the lower body (primarily the groin, tibiofemoral and patellofemoral components of the knee, and the IT band), plyometrics found in basketball and football, and the shoulder/elbow care acronym, RAMS, in baseball (Recovery, Activation, Mobility, Strengthening).

The second focus should be the analysis of long-term and cumulative wear impact on body and system function. Several injuries which are regularly found in ultimate players such as ACL/LCL strains, IT band strains, shin splints, etc., are all associated with overuse of the legs. UCL injuries (sustained from regular, unrested overloading of the elbow through the flick [forehand] motion of throwing the disc) and rotator cuff injuries (resulting from repeated hammer and thumber throws) have become more prevalent as offensive and defensive approaches have evolved and the sport, much to the dismay of traditionalists, has continued to draw bigger, stronger, and faster athletes. This is especially true in handlers who are responsible for regular distance throwing and complete anywhere between 100 to 200 throws over the course of a six game tournament.

My third concern would be the creation of incremental exercise and stretching programs which focus on the gradual development and loosening of muscle and ligament groups before a competition. A warm-up jog with a thorough, full-body stretch and supplemental throwing warm-up, would be a good place to start for most beginning players. Incremental throwing before a practice or tournament day, progressing from 10 yards to max distance (say 65-75 yards for handlers) is a page out of the baseball playbook, but one which is dangerously overlooked by many at the beginner and intermediate levels of the sport.

There is no easy way to change a sport, especially when attempting to institute a paradigm shift related to the culture of the activity. In recent years, though, various individuals and companies have come out attempting to drive such a shift. The development of ultimate specific cleats, training equipment, and exercise regimens is a step in the right direction, but can only do so much. Unfortunately, we are at a point in the community where multiple narratives are coming to a head. The least of these, at the moment, is the physical well-being of athletes across the sport. Until it becomes a priority, we will continue to see plays such as this.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion