On September 14, 2018, former U.S. Secretary of State and 2004 presidential candidate John Kerry sat down on "Real Time with Bill Maher" to sling some insults at Donald Trump. Trump had, of course, started it; he had tweeted a typical capslock evaluation of Kerry's character ("BAD!") the day prior.

Kerry's assessment of Trump—"we have a president, literally, for whom 'the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth' is three different things," he quipped—was mostly satisfying, given that we seem to be living in a country where pointed humor is a necessary defense against the erosion of democracy. But then he compared Trump to a teenage girl.

Specifically, he joked that Trump exhibits the maturity of an eight-year-old boy and the insecurity of a teenage girl.

I'm not going to comment on whether that characterization is fair to eight-year-old boys, but as someone who qualifies as a teenage girl for another year—which means I'm both offended personally and protective of all the much younger teenage girls—I do take issue with the second half of Kerry's description.

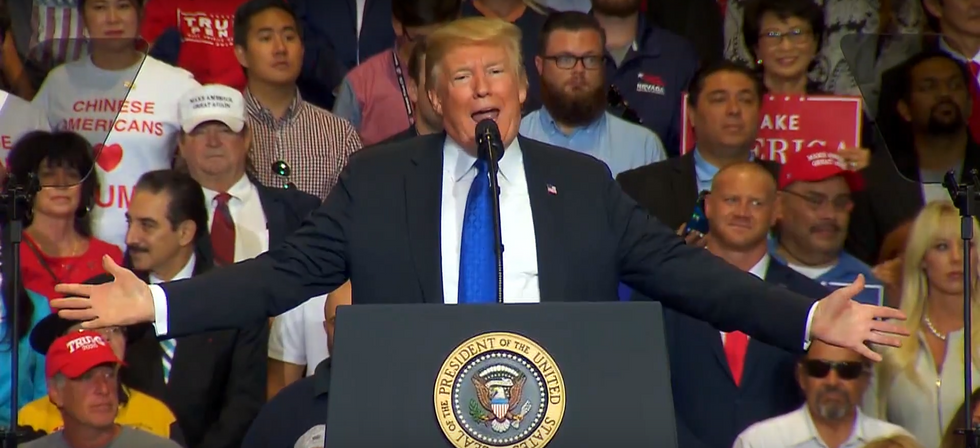

The underlying truth of it is undeniably valid: Trump is insecure. He specializes in spewing below-the-belt Twitter insults at anyone who challenges him; he compulsively boasts about his own superiority, even in such tragic circumstances as Hurricane Maria and 9/11; and he gets too heated over personal jabs that more stable political leaders would probably ignore in favor of responding to on-topic criticism.

So Trump is insecure.

So are teenage girls, to be fair. But that's not an inherent consequence of being teenaged and female. We as a society just accept that it is. And jokes like this not only perpetuate that misconception; they make light of it.

Sure, being a teenager of any gender is hard: You're expected to behave like an adult while being treated like a child, and you're conscious for perhaps the first time that you're a human being with a role to play in the larger world. It breeds insecurity.

But it's not a coincidence that John Kerry specified the gender of the hypothetical teenager in his joke; girls have a reputation for being insecure and boys don't. Because on top of the baseline teenage woes, girls are bombarded with messaging taking aim at their self-worth.

Advertisers make big bucks tearing girls down in order to convince them that they would be better off if they bought this beauty product or that one. Magazines and social media circulate images of computer-generated waists and curves. And social media also traffics in vitriol: It's incredibly easy for any man with computer access, up to and including the President of the United States, to publicly demean women with a few keystrokes.

In every aspect of our lives, from pop culture to politics, women are targeted, because our insecurity is profitable. It boosts the egos and lines the pockets of the people who encourage it.

Which means that teenage girls aren't insecure because they're teenage girls. They're insecure because they're teenage girls in a patriarchal society.

And there's something distasteful about comparing Trump, a proud agent of the patriarchy, to victims of the patriarchy's toxic effects.

It's also a somewhat inaccurate parallel. The insecurity of teenaged girls commonly manifests itself in eating disorders, dependence on photo editing apps, and self-deprecating remarks.

But Trump has a privileged man's insecurity. Unlike that of teenage girls, his insecurity is externally-focused. He tries to drag others down to prop himself up. He insults the appearances and performances of others, not his own. He doesn't try to change himself. He expects the world to change on his behalf.

Girls get insecure because of the world's expectations that they be superhuman and then take that insecurity out on themselves. Trump gets insecure because of the world's expectations that he be human, and he takes that insecurity out on everyone else.

There's really no comparison. Making one is unfair to teenage girls everywhere.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion