The art of Japan is, in my eyes, some of the most breath-taking in the world. When I speak of Japanese art, I am sure your minds have jumped to something familiar. Perhaps you have conjured up an image of the, Dragon Ball Z manga or anime, or maybe thought of the recent, ever-popular, Pokémon Go. Quite reasonably so; manga, anime, and video games are perhaps the most popular forms of Japanese art shared across the world today. The stories and artwork created by, Mangaka, or, ‘manga artists,’ animators, and video game designers captivate a global audience. (Music, live-action movies and television series from the country are also quite popular). Whether it is because of their comedic elements, action-packed narratives, or vibrant, colorful romances and fantasies, these forms of art have brought joy to millions; myself included. This impact is most evident when we hear about or attend anime conventions or explore the, “fandoms” created by large communities to celebrate their favorite manga, anime, and/or game series. What you might not be as familiar with are the classical periods of Japanese art. Then, perhaps you do know of some classical Japanese art; ukiyo-e prints, kabuki theater, and traditional music have impacted several aspects of Western society, (especially in the realm of art, particularly during the Impressionist era; Van Gogh, anyone?). Though maybe you possess some misconceptions about the artwork, either due to common themes or stereotypes spread around. I have noticed over the past few years I’ve spent delving into classical Japanese art, that there are several misconceptions about the classical artwork of Japan. I’d like to take you on a journey to the East, and disclose to you what I feel are the top three misconceptions about art from Japan. In learning these misconceptions, perhaps you can begin to see the beauty in the classics and discover more of what makes the modern so magical.

(Disclaimer: Just as with Western art, Eastern art has crossed many time periods and has gone through many cycles. There is a plethora of art from Japan to be enjoyed and discovered. For this article, I will be examining classical Japanese visual art as a whole, not just focusing on one particular period. If you are interested in Japanese art, whether classical or modern, you are encouraged to do your own research, and visit museums with Japanese art sections. You’ll be amazed at what wonders you’ll find).

Let’s begin!

Misconception #1: Japanese Art is Expressionless

Facial or body expressions are important aspects of the human subject in art. Many of us in the West, however, expect to see a twisted face for anger or pain, a frown for sadness, a note of coolness for indifference, a wide smile for happiness, or various other emotional expressions in art. Therefore, many people might contemplate a print of a geisha, and presume her to be, “wooden,” in comparison. In truth, classical Japanese art possesses expression in an abundance; perhaps it is just not the expression we are used to seeing.

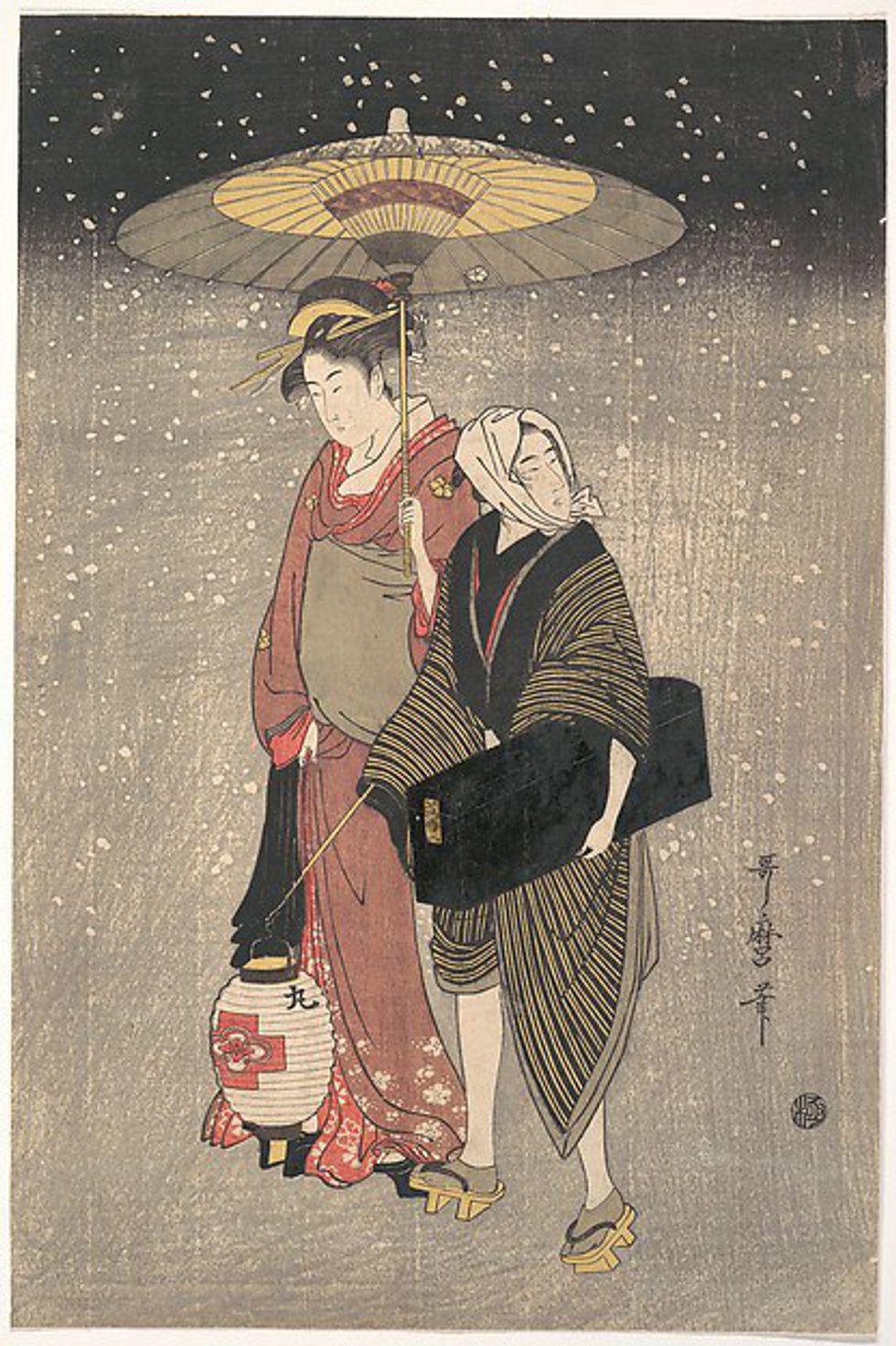

In the book, Myths and Legends in Japan, author F. Hadland Davis explains, “The Japanese face in art is not without expression, only it happens to be an expression rather different from that with which we are familiar…” He goes on to say that due to how we are taught about shading and lines in the West, we often deem the faces we see on Japanese prints and paintings to be, “very bad art,” for their inherent flat appearances. Of course art itself is subjective, but the lack of shading or note of every, intricate facial detail does not immediately deem it bad or wrong. Rather, the artists at the time sought to capture an idea of what they saw when looking upon the faces of men and women in their country, much like any Western artist desired to do. This different kind realism or expressionism in Japanese art can most likely be attributed to their lack of contact with many others in the outside world for centuries; however, this is just a speculation. Nowadays, there is certainly plenty of expression in the art originating from Japan, though it is interesting to revisit its roots. There is undoubtedly something hauntingly, beautifully expressive about a geisha’s gaze. One just has to look at the art from a different point-of-view.

Geisha Walking through the Snow at Night, Kitagawa Utamaro, Edo Period, 1797

Misconception #2: There are Few Subjects Aside from Nature and Women

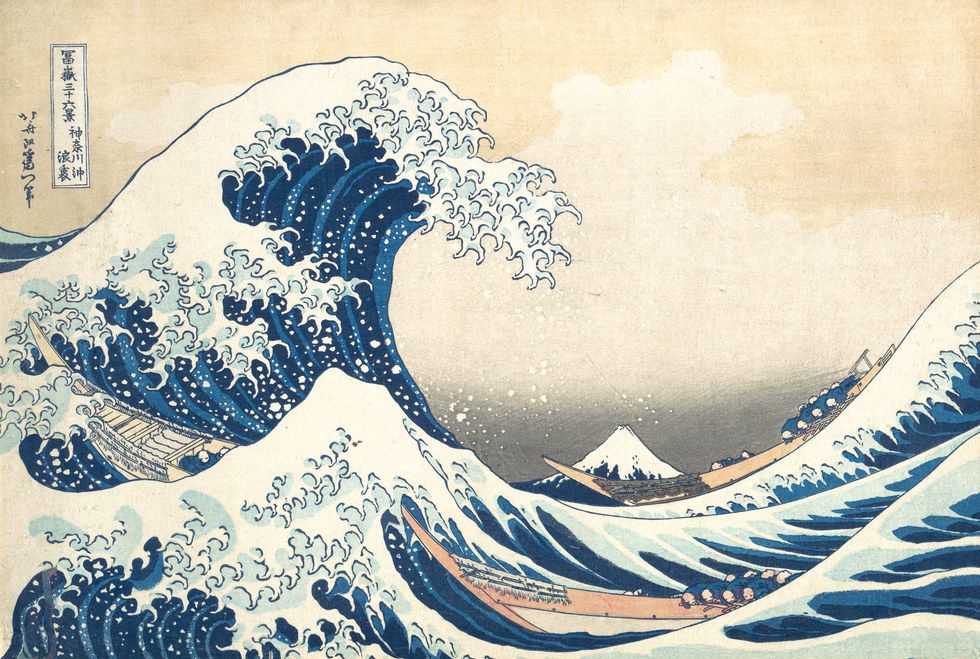

It would be foolish to deny or contest the skill and beauty apparent in Japanese prints, poetry, paintings, sculptures, etc., featuring nature and women. There is no doubt that these two subjects were popular throughout the centuries. Many of the masters of ukiyo-e and other forms of art made their, “claims-to-fame,” as it were, due to their astounding abilities to capture the delicate intricacies found in both nature and the feminine form. For example, one of the most famous Japanese prints, The Great Wave, painted by renowned printmaker, Katsushika Hokusai, is a nature piece. Most people know of the deep, rich blue of the waves, carefully traced with white foam, the ships that succumb to its virility, and Mount Fuji proudly standing in the background; it is an unmistakable, unforgettable image. Many works depicting women, such as courtesans, geisha, and occasionally the every-day woman, have also become some of the most notable, such as those created by printmaker, Kitagawa Utamoro.

The Great Wave, Katsushika Hokusai, Edo Period, 1830-32

The Nakadaya teahouse, Kitagawa Utamaro, 1794-95

However, there are also many other subjects depicted in the art of Japan. Gods and goddesses, the Buddha, stories from the religions, Shintoism and Buddhism, the Imperials, samurai, fantastical beasts, as well as street scenes and glimpses into the lives of the common folk can be found in many works throughout the Japanese art timeline. Even monsters and demons are featured in art, (something we’ll touch upon more soon)! Any look through a book containing photos and information about Japanese art will quickly reveal the artists’ interests in creating more than just things of delicacy or beauty. Much like today, there are scores of subjects that inspired the creative mind. Speaking of which…

A Cauldron on a Moonlit Night (Tsukiyo no kama), from the series "One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi)", Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1886

This interesting, active scene is just a sample of the variety of subjects found in Japanese art.

Misconception #3: The Art Never Portrayed the Grotesque:

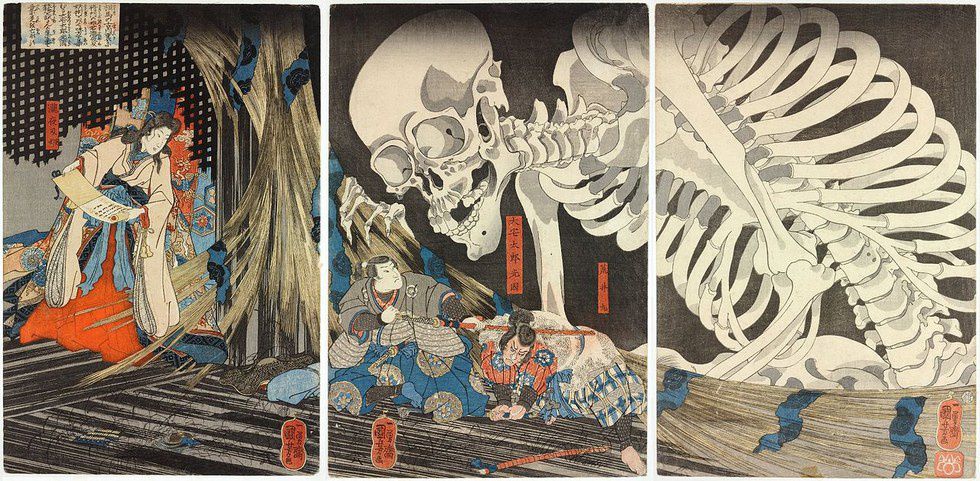

Japanese art of any kind is often noted for its poeticism. There is something wonderfully flowing and rhythmic about Japanese art. Their fondness of poetry and the practice of writing it undoubtedly had a part to play in the natural fluidity of their artwork. Not only did their other experiences and interests find a place in art, but so too, did their disciplined environment. It was common practice to put one’s whole heart into one’s work, no matter what the work entailed. The heart of the artist was so strong, so methodical, that it was said at one time by a Japanese art critic, author F. Hadland Davis, “If in the midst of a stroke a sword-cut had severed the brush it would have bled.” Bled surely, like an artery, as the brush had become an extension of the artist’s own body. This attitude towards art is what helped bring to the world the ethereal scenes we often find in Japanese works from the past and today. This worked in conjunction with their poeticism, and allowed them to create marvelous scenes and figures, powerful yet fragile. However, do not let the serene mountain passes and dancing women fool you; there were sinister sides to the works from the past! Some grotesque, phantom-like imagery was created throughout the centuries. Much of the beasts, monsters, ghosts, and evil spirits—or, Oni—from their religions and legends make appearances in enormous works of art. There are many spirits with which the ancient Japanese person had to contest, and because of their deeply-held belief in and understanding of the otherworld, they could relate to artworks portraying them. They could serve as cautionary tells, or tell the stories of the heroes that stood down the monsters of myth. Many prints and other artworks that portray creatures of this nature often relied on the artist’s use of darker color palettes, and larger formats. Properly capturing the terror of a demon was surely something of a chore, but one done undoubtedly with care. One will quickly find that, even in the images and forms of the demonic, there is something graceful and wispy. Today, there are a great deal of beings that have been born from legendary monsters of the past in Japanese art, and still, one will notice that there is a beauty within the beasts. (Some, “monsters,” are even cute!)

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter from the Story of Utö Yasutaka, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1843-47