What is the first thing you think about when you hear of HIV? Perhaps that it's a harsh and seemingly unbeatable disease? Common in the '80s? Sexually Transmitted? Freddie Mercury and Rock Hudson suffered from it?

The human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, attacks the body's immune system, more specifically the CD4 T cells. Over time, the virus can destroy so many of the body's CD4 T cells that it can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, better known as AIDS, where a person is more susceptible to infections or infection-related cancers.

How is HIV so powerful?

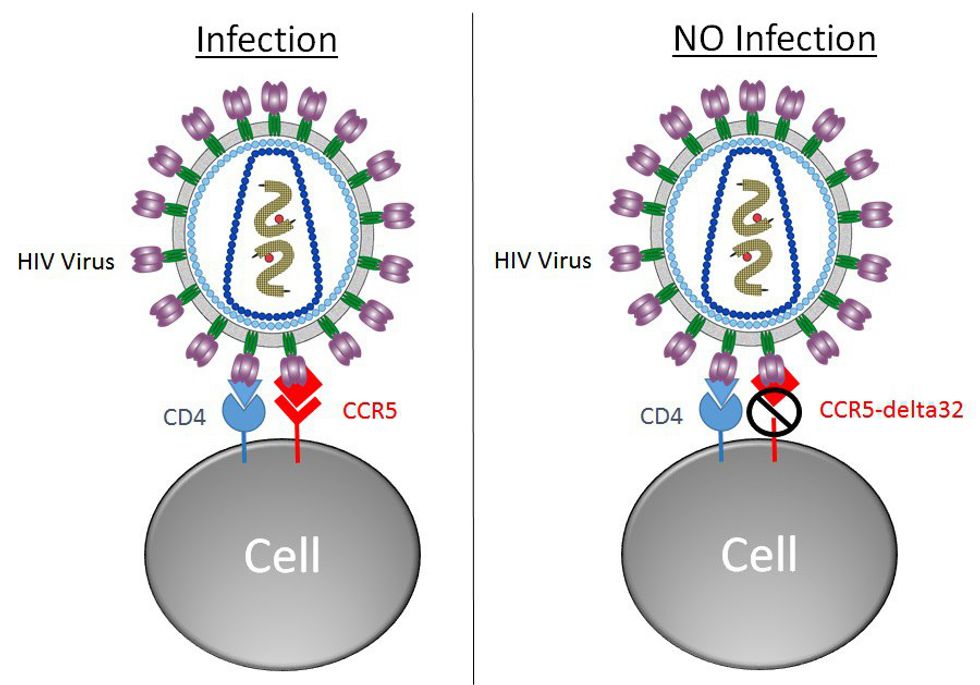

For a cell to recognize outside messages so that it can transmit them to the inside of the cell, it needs a type of receptor on its surface. CD4 is the cell receptor on the surface of the T cells. When HIV enters the body, it tricks the immune system not to attack while it makes it's way to grab on to the CD4 receptor and inject the T Cell with its DNA for replication.

The reason HIV is such a savage disease is that the body's defense system is under attack and it is incapable of fighting back. Not only that, but HIV is so sloppy at copying its genetic information that it mutates quickly with the favorable survival characteristics from its previous version before a new drug is found to defeat it.

What if someone told you that there are people immune to HIV?

In fact, in about 1 percent of Caucasian people, that is the case. It turns out that the CD4 receptor on the T cells isn't enough to let the DNA from the virus inside. With the help of another protein, CCR5, a coreceptor that works alongside CD4, functions as the "door" that allows HIV to enter the cell.

The lucky few that are resistant to HIV have a mutation in the CCR5 gene called CCR5-delta32.

In the CCR5-delta32 mutation, a smaller protein that doesn't live on the outside of the cell anymore is produced. Most forms of HIV cannot infect cells if CCR5 is not present on the surface.

Those with two copies of the CCR5 delta32 gene (inherited from both parents) are virtually immune to HIV infection. One copy of CCR5-delta32 doesn't provide the same protection against infection but it does make the disease less severe if infection occurs, that is why it's more common, it is found in up to 20% of Caucasians.

Could this little-known fact be the cure for HIV 35 years into the epidemic?

Theoretically, blocking CCR5 should stop HIV from infecting the cell. Scientists are working hard to develop a drug that barricades the CCR5 receptor so HIV can't use it. However, that means there is a risk of having severe side effects because it would be blocking your body's proteins. It is also likely that HIV could mutate into some super species that finds a way to infect a cell without the CCR5 receptor.

Nevertheless, a cure could be in sight. Maybe you could be the one to find it.