I've amassed a fair collection of articles about grammar at this point. You might say I'm pretty passionate about the subject. I always loved to write, but I think that passion really took hold when I was in seventh grade and I had to learn Mr. Schmittou's infamous "Grammar Rules," iron-clad dictates for any kind of writing in his language arts classroom. For years afterward, I wrote them in the backs of my notebooks and followed them to the letter. They were burned into my brain to the point where even the ones I didn't quite remember I still followed without thinking about it.

Then I got to college. Most of Mr. Schmittou's Grammar Rules still applied, but I began to learn -- and was even encouraged -- to break them. Not that my professors knew that they were encouraging me to break Mr. Schmittou's Grammar Rules, but they were encouraging us to write unbound by the conventions that had been drilled into our heads for years. One by one, I began to break Grammar Rules. It was uncomfortable at first, but when I did it, my writing had more voice and more variation in it than it had had for a long time.

I want to share three of these Grammar Rules --and the ways to break them-- with you because I'm really strict about rules and writing in a lot of my articles, so I think it's time we broke some.

1. "Do Not Begin Sentences With Conjunctions"

There's a way to do this and a way not to do this.

I started breaking this Grammar Rule thinking it wasn't particularly okay that I was breaking it, but then I read this beautiful article on one of my favorite grammar sites and I learned that "just about all modern grammar books and style guides agree" that it is okay to start a sentence with a conjunction! We've probably been banned from using them this way because teachers noticed that their students were overusing them, and rather than teach them the proper way to begin a sentence with them, they just banned them at the beginning of a sentence outright.

So, time to un-learn what you've learned.

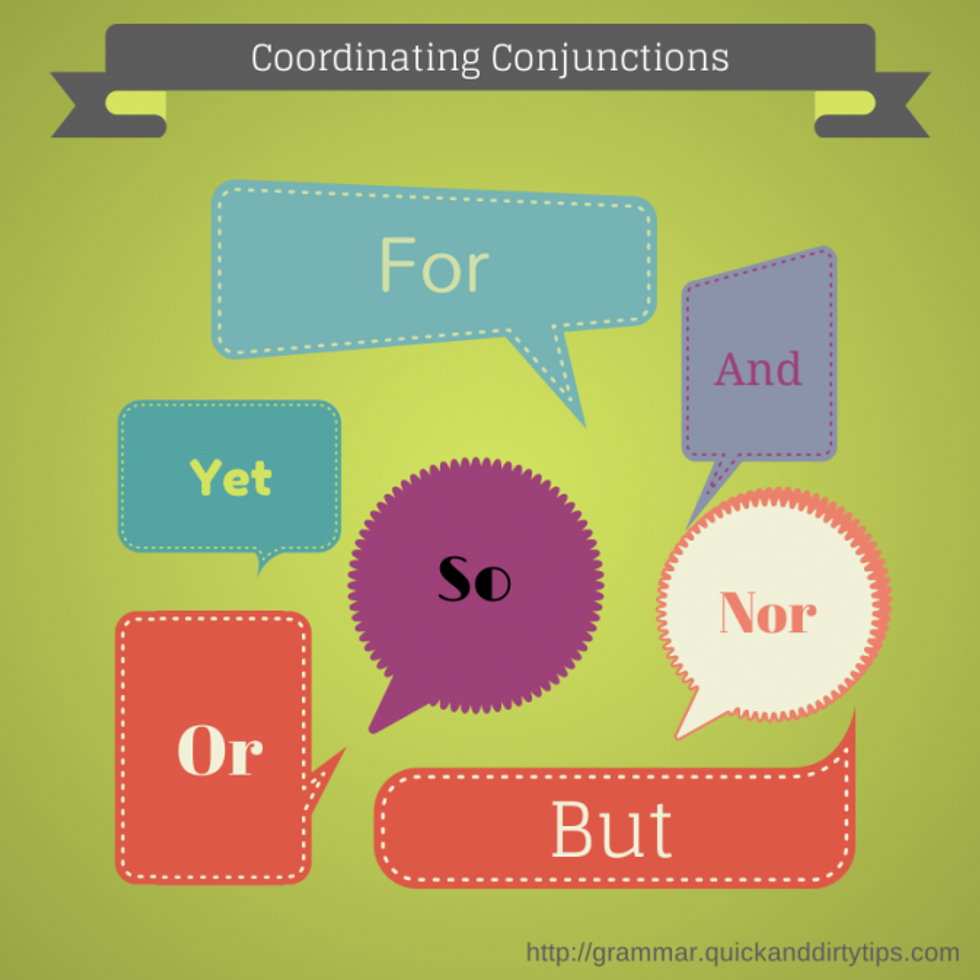

According to the article, it's perfectly fine to start a sentence with something called a coordinating conjunction. There are seven of these -- handily listed in the graphic above -- and the easiest way to remember them is to memorize them. There's an easy mnemonic for this: "FANBOYS," which stands for for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so.

It's pretty cool.

Coordinating conjunctions won't turn your sentence into a fragment like other conjunctions can. Memorizing this mnemonic (instead of the reasons why other kinds of conjunctions don't work the same way) is much easier when you want to start a sentence with a conjunction, but don't know if it will work.

2. "A Paragraph Must Have an Introduction, Body, and Conclusion"/Using Sentence Fragments

I'm going to lump these two together, because one of the earliest criticisms I received when I got to undergrad was that my sentences were too long, that I needed to break up my paragraphs a bit in order to keep my reader's attention. I felt like that fit in rather nicely with this Grammar Rule.

I mentioned in the section about using conjunctions at the beginnings of sentences that there are some conjunctions that can turn your sentences into sentence fragments. The Purdue Online Writing Lab (aka the "Purdue OWL") describes sentence fragments as "incomplete sentences... pieces of sentences that have become disconnected from the main clause." A clause is a group of words that contains a verb and can stand on its own as a sentence.

That's a lot of explanation, so I've provided links to good sources to give you more details.

I'm going to use an example from the Purdue OWL page on sentence fragments as an example to cover both of these ideas because I think it could actually work really well in creative writing. The example they give is this:

"I need to find a new roommate. Because the one I have now isn't working out too well."

The sentence fragment is in bold so you can easily identify it. Their suggested fix is this:

"I need to find a new roommate because the one I have now isn't working out too well."

This is perfectly correct.

And boring.

There's no voice in the sentence -- the tone is very flat. The article from the previous section on conjunctions describes "the combination of a sentence-final pause and a sudden afterthought delivered in a short burst" to create the effect of surprise. This is based in personal opinion, but in this case, the fragment is that surprise: the first example makes me wonder why this roommate isn't working out -- maybe there's something sinister or weird behind it. The second one makes me think they're just a bad roommate. The fragment adds some depth to the writing.

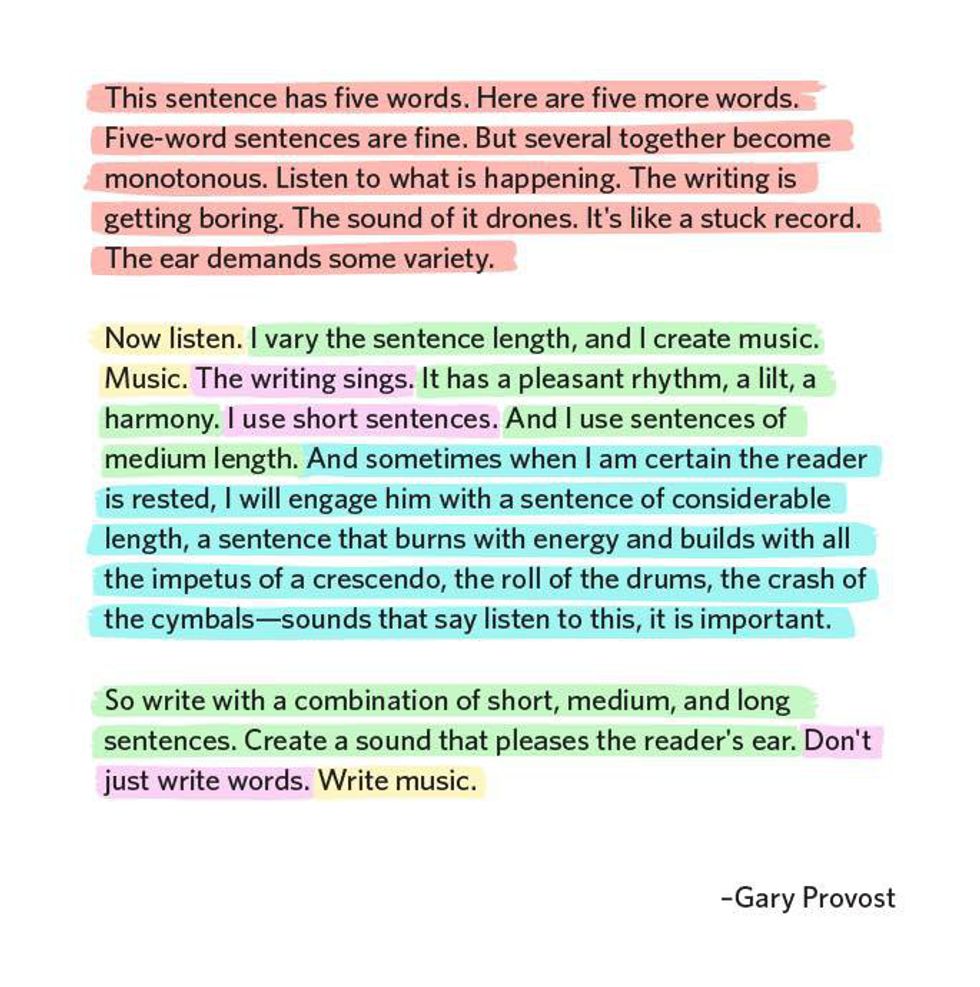

There is really only one sentence here that could be considered a fragment: "Music." But look at what that repetition does--it drives home that what Provost is doing isn't just putting marks on paper, it's creating. It's composing. It's art, just like music is.

We could also try it as not just two separate sentences, but as two separate lines, like if this was a character narrating that they needed to find a new roommate:

"I need to find a new roommate.

Because the one I have now isn't working out too well."

This is a more intense pause than a period and implies serious problems. Even if those serious problems are just that this roommate is leaving dishes in the sink for three weeks and allowing them to sprout mold. Not that I know from experience what that's like or anything.

These lines would be indented as separate "paragraphs," though, and they definitely do not have an "introduction, body, and conclusion": there's no topic sentence -- not even a hint of one -- that is then explained and wrapped up, even if it's only wrapped up in a minor way.

An even better example that's right here in your face? When I described Purdue's sample revision as "boring." I not only started that sentence with a conjunction, but it's a sentence fragment, and it's a standalone line -- and I would type it that way in an essay, with its own indentation and everything -- but offsetting it that way emphasized precisely how dull I thought that sentence was.

Used intelligently, sentence fragments and short paragraphs can really pack a punch and drive your point home!

By the way, my response to that professor who told me to use more short sentences? "I'm trying to. Really, I am."

I think he got the humor.

3. "Do Not Use Contractions"

As you can probably tell, I've relaxed on this one quite a bit. This is, I think, one of the best tools for helping to make something more relatable, and to make it sound more genuinely like you. Amusingly, while browsing, I found an article on my favorite website about using contractions in writing, and learned that, once again, "[m]any style guides even recommend using contractions" above and beyond stating that they're simply okay to use.

Quoted in the article from the "Plain Language" website is some very good advice:

"People are accustomed to hearing contractions in spoken English, and using them in your writing helps them relate to your document."

Furthermore, using contractions lends itself to your own unique voice: would you have used "it's" instead of "it is" if you were speaking to an actual person? Using contractions -- sparingly -- can enhance your writing, making it sound more like a person is behind it and less like some kind of grammar machine wrote it.

HOWEVER:

There are good reasons for not following the advice above.

The first and best reason, by far, is if you don't agree with it. You don't always have to follow all of the advice you're given, even if it's a teacher or professor giving it to you (it might be helpful to adopt some practices temporarily so you don't blow your grade, though).

Second...

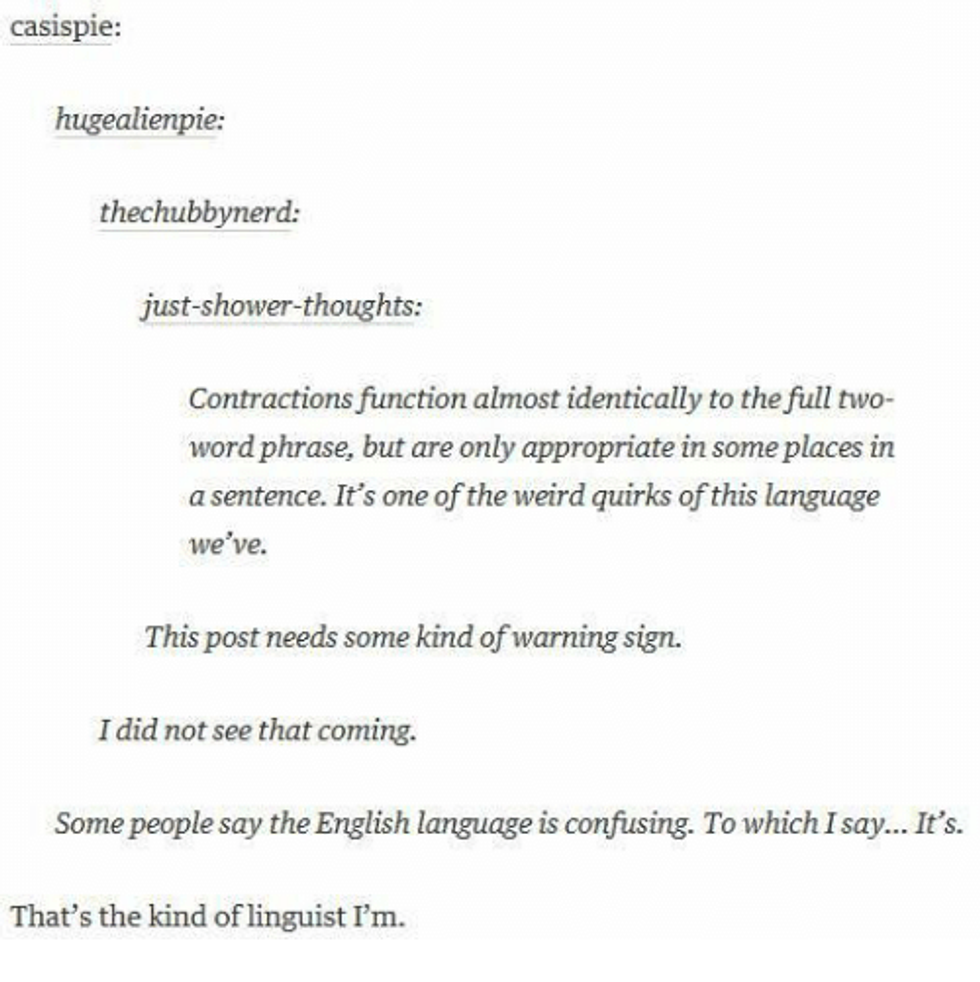

... is if it's out of place. Contractions don't go everywhere you could use one, and this post does a great job of pointing that out.

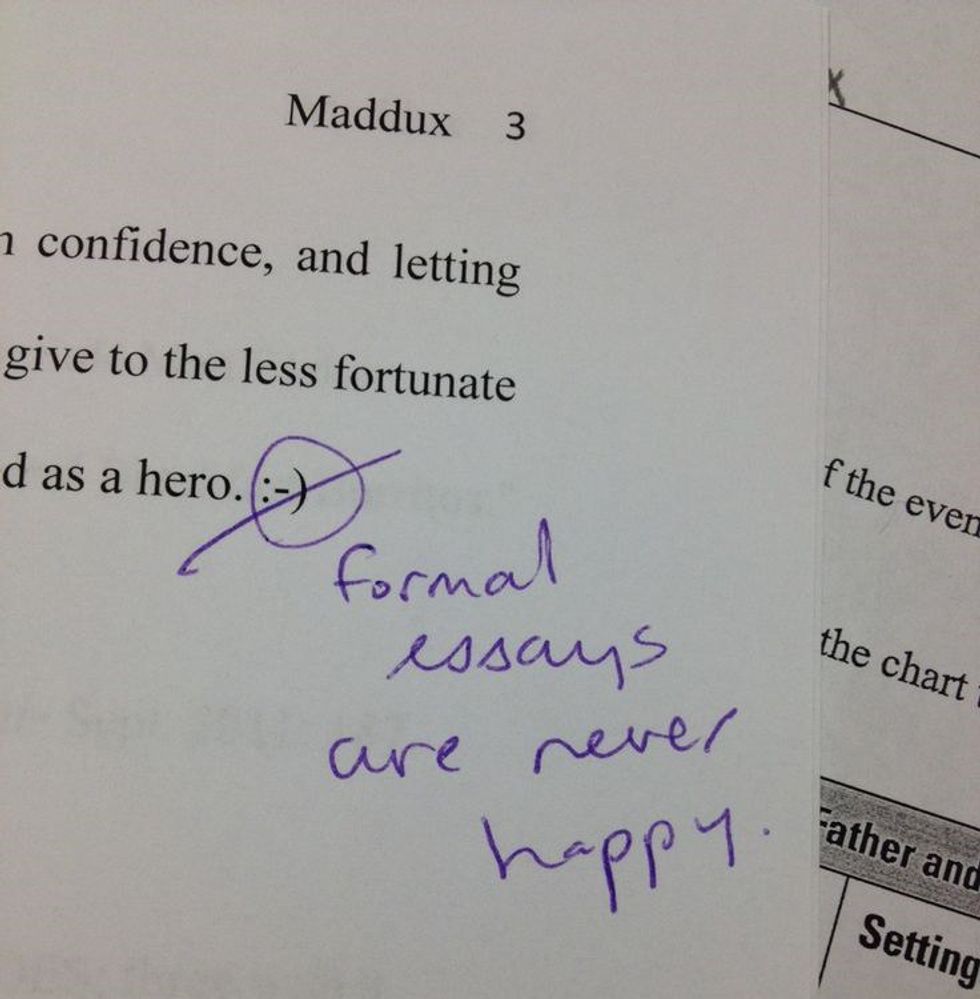

Probably the second best reason, however, for not doing something I've suggested above is a formal essay, particularly when your teacher or professor tells you precisely what he or she wants from you.

I can't imagine the wrath I would have incurred if I would have turned in an essay to Mr. Schmittou with broken Grammar Rules and justified it with "the internet told me to do it." During my undergraduate career, I had that one professor I mentioned before tell me to use shorter sentences, while another encouraged his students to write lengthy sentences and have our paragraphs take up entire pages. The latter also mandated that we avoid contractions entirely. Still another professor encouraged us to use contractions because she wanted us to write as we would speak, more or less: we should of course refine it for a university environment, but we were not submitting theses, and she wanted us to get creative.

My point is this: for a lot of your writing, you can ease off on what your high school teachers burned into your brain, but before breaking any big rules, make sure it's okay with the person giving you a grade.