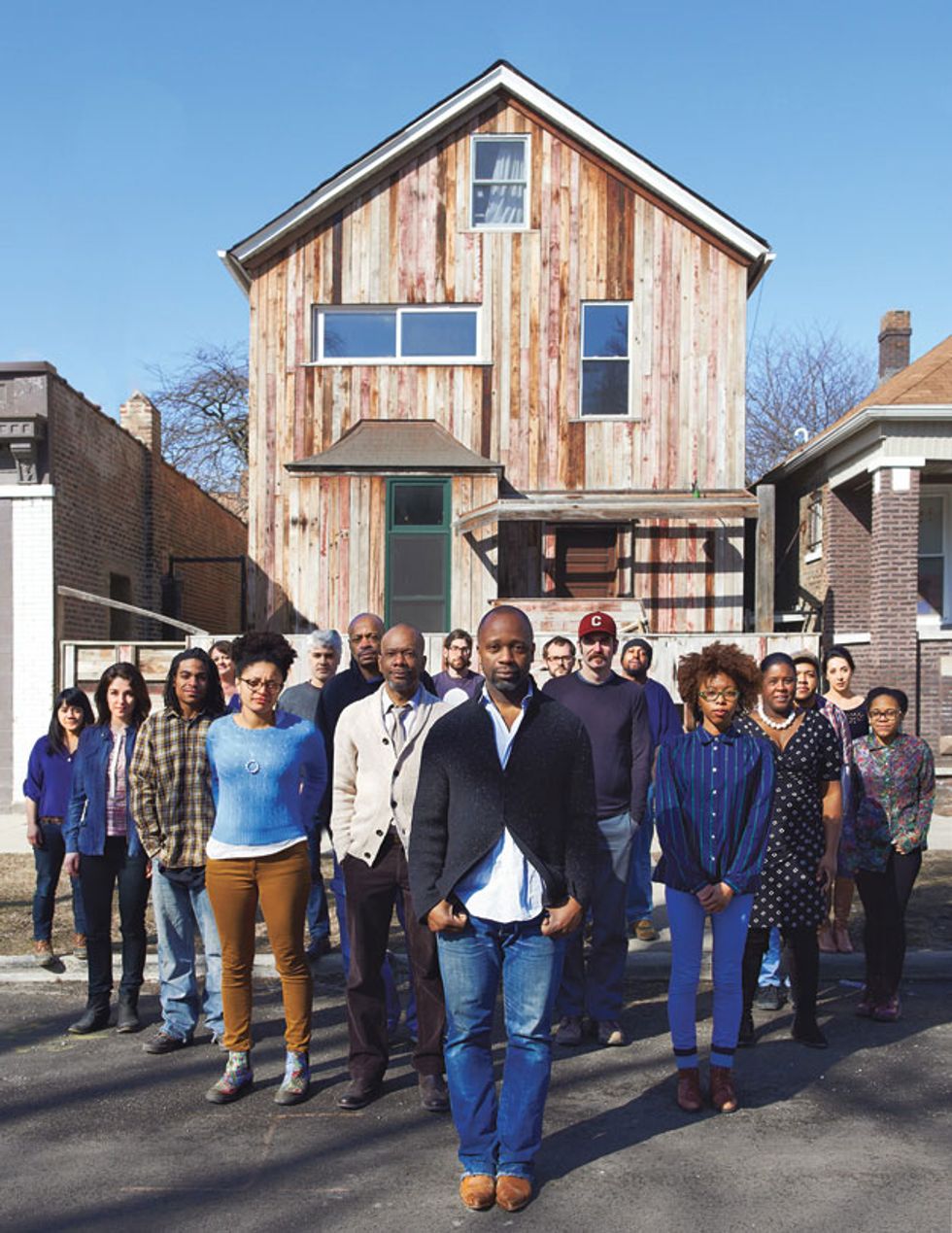

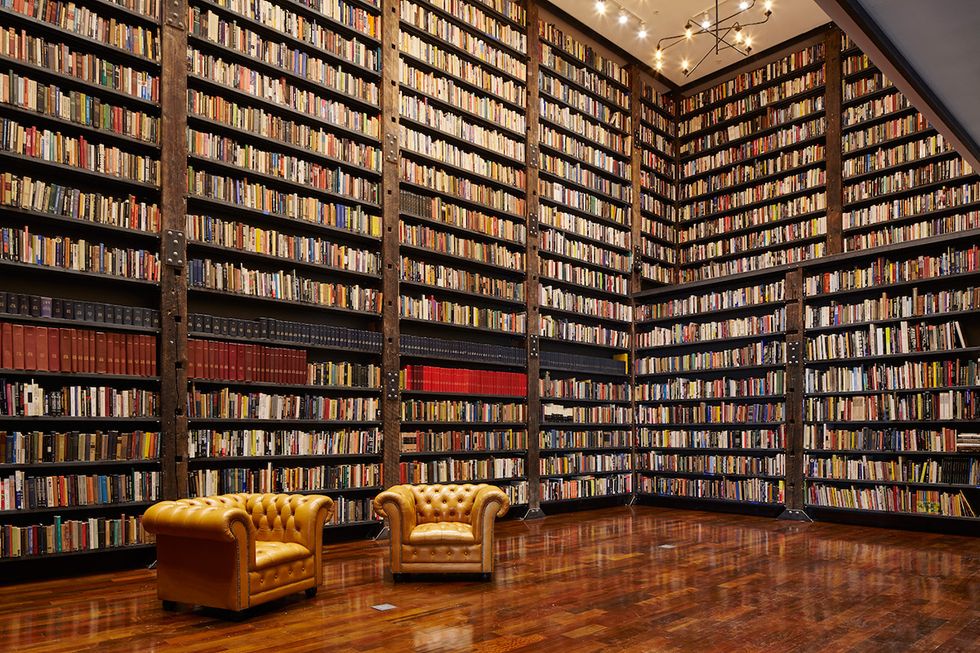

If you have never heard of Theaster Gates, you are about to experience the world of social justice with new eyes. Theaster Gates is a revolutionary artist, activist and cultural worker. The creator and director of the Rebuild Foundation, his work combines urban planning and cultural programming to revitalize poor neighborhoods. In an initiative called the Dorchester Projects, he has transformed a run-down neighborhood in Chicago’s South Side by renovating several buildings and converting them into cultural centers. A residential house has become an Archive House with over 14,000 books; a local candy store is now the Listening House for community gatherings; a former distribution facility accommodates a Black Cinema House; and a bank is home to myriad rotating art exhibitions and artist residencies.

The Archive House

Stony Island Arts Bank

Gates began his artistic career as a potter. He often draws on a pottery metaphor in relation to his current work – clay is easily moldable but also liable to crack and break when hardened. Similarly, Gates sees himself as cultivating (or “molding”) the Dorchester neighborhood of Chicago into one that fosters community and art, rather than poverty and violence.

Pottery also generated Gates’ career as an artist, which gave him the income to even buy and renovate the Dorchester buildings. In 2007, he began hosting soul-food dinners to showcase the pottery of Shoji Yamaguchi, a Hiroshima survivor who fled to Mississippi and incorporated both African-American and Asian styles in his pottery. But there was one catch – Yamaguchi was not a real person. All of his pottery was actually created by Gates. The pieces sold for hundreds of dollars each; before Yamaguchi, Gates could not sell anything for more than $25.

The Yamaguchi plan is just one example of Gates’ deep knowledge of how the system works – and how to take advantage of it to create change. He knew that the interesting Yamaguchi story would sell more pottery than he ever could as a black artist. This skill is evident in myriad aspects of his method. For instance, after Gates bought the bank that he renovated into the Stony Island Arts Bank, he removed several marble slabs, carved “IN ART WE TRUST” and his signature on them, and sold them for $50,000 each to fund the renovation process.

Gates reads books on zoning laws; he partners with powerful people who do not fully understand his purpose; he faces continuous criticism that art does not adequately impact social justice for impoverished people.

But the Dorchester Projects have transformed the neighborhood. And as his cultural work becomes more well-known, his art becomes more valuable and thus can be sold at a higher price, which gives him more money to renovate buildings – and thus the project spurs itself. In a Robin Hood-esque fashion, Gates uses his artistic genius to both create his own work and archive the art of others.

In late March, Gates visited Brandeis University to accept the Richman Distinguished Fellow in Public Life Award, after which he performed “A Cursory Sermon on Art and the City.” The day before, he also held a Q&A with the introductory course for the Creativity, the Arts, and Social Transformation (CAST) minor. He discussed his artwork, his cultural activism, and challenging the systems that bind not only Chicago’s residents, but people of color in poor neighborhoods across the nation.

Gates is a fascinating speaker, smoothly shifting between the practical and the poetic. “A real life is one of misunderstanding and contradiction,” he commented in relation to navigating the system while staying true to his internal “soul-work.” He imparted key ways to uplift impoverished communities, like hiring people who already live there instead of soliciting outside labor. He also spoke of art’s power to psychologically transform a community by imparting values – which he realizes are not answers – that diminish urban violence.

So you are fascinated by Gates’ work and his non-traditional approach to activism. As a college student, what can you do? Gates offered advice to students, especially undergraduates, who recognize the power of youth activism and want to use art for social transformation. First, he encourages being able to self-prompt rather than relying on a prompt from someone else. When your prompts for action become self-generated, you can become a catalyst for change. He also stresses that undergraduate institutions should not exist just for job readiness. Education should prepare you to develop a unique skill set that leads you to a career. And with the ability to self-prompt, you can create your own career rather than following a prescribed path.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion