Within the last two decades, Hollywood’s superhero myth has evolved from the simple to the complex. New breeds have risen from this movement: the conflicted hero and the antihero. As black and white depictions of morality become archaic, shades of gray dominate the moral spectrum.

It is no longer a simple question of how to save the damsel and defeat the evil power. It becomes more a question of “why?”

No longer is it sufficient for a superhero to be an advocate for “truth, justice, and the American way” (Superman: The Movie 1.30.30). A superhero still must have a personal moral code, but the audience does not have to agree with it. However, if the audience does not feel connected to the hero, then they are less likely to enjoy the movie. The audience must be able to understand the antihero’s moral point of view in order to identify with the anti hero.

In a postmodern age, people are no longer satisfied with a simple good-versus-evil worldview. Similarly, they are no longer comfortable with letting the government solve their problems, or entrusting their health and safety to those in power. With a culture that is increasingly focused on self, the individual's desire to take matters into their own hands increases.

In superhero comic books, this is addressed by the Revisionist movement. In "The Amazing Transforming Superhero!, journalist Brendan Riley explains,

“revisionist texts featured antiheroes who killed too often and brooded too much”.

Audiences want to feel empowered. But rather than watch an omnipotent man in a cape fly around and solve all of their problems, they want to see a mirror image of themselves, twisted and flawed, but willing to do whatever it takes to defend their own personal ideas of right and wrong.

Superhero morality is a relatively recent topic of debate, as before it was mostly a simple answer: the morality of a superhero is Good, and the morality of a villain is Evil. Now that it is up for debate, there has been a rise in films like The Dark Knight and Watchmen, where the heroes either question their own ethics, or the audience is forced to.

With ever increasing shades of gray, it is harder to expect an audience to fully endorse their hero. In the superhero film genre, the audience must be able to recognize the conflicted hero or antihero’s morality through the protagonist’s actions, motivations, and internal struggle.

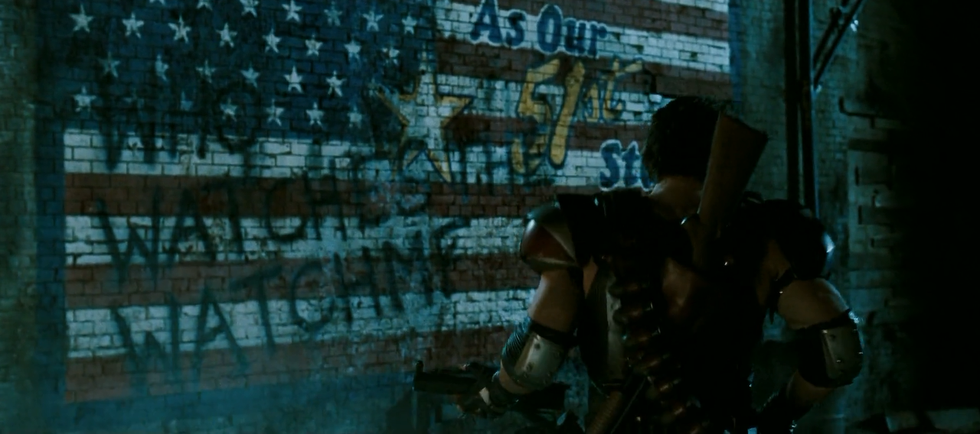

The antihero stands alone, having definite actions but compromising motives. A prime example of this is the 2009 film, Watchmen, in which none of the heroes are certain of their beliefs except for the self-assured villain. The film begins in an alternate 1985 where Nixon is elected for a fourth term and the Cold War drudges onward. The superheroes are masked avengers, sponsored by the government to instill fear in criminals as well as to discourage foreign enemies. But as the Cold War gets hotter, citizens protest the heroes, claiming that they are more of a hindrance than a help.

After dispelling a riotous mob, vigilantes Night Owl and The Comedian reflect on the work that they are doing. Night Owl wonders if it is necessary at all. To this, The Comedian responds, “We’re society’s only protection[…] from themselves” (Watchmen 0.52.50). Though to the audience, this truth is ironic coming from the mouth of The Comedian, since he is clearly a sadistic killer. A flashback reveals the Comedian in combat during the Vietnam War, smiling devilishly while incinerating his enemy with a flamethrower (0.45.00). It is implied that his motivation is not a moral code, but pleasure. The logical result would be a character that is wholly unlikeable to the audience. To remedy this, the audience must be able to connect to him in some way.

As time goes by, The Comedian is shown to be growing soft; less sadistic and more sympathetic. He goes to meet his former arch-nemesis, Moloch, to whom he pours out his heart. As years of ignored human emotions begin to flow, The Comedian admits to his personal struggle and confusion: “I thought I knew how the world was. I’ve done some bad things” (Watchmen 0.56.50). As the audience realizes that even this twisted man can have a conscience and a change of heart, they immediately begin to identify with him. The idea of repentance for even the most damnable of characters is something that audiences cling to because regret is a deeply human emotion. Seeing such a dark character move from the black moral realm into the gray is encouraging and gives the audience a sensation of hope. The Comedian’s actions are for the most part justified by law, and although his motivations are sinister, his personal struggle redeems him.

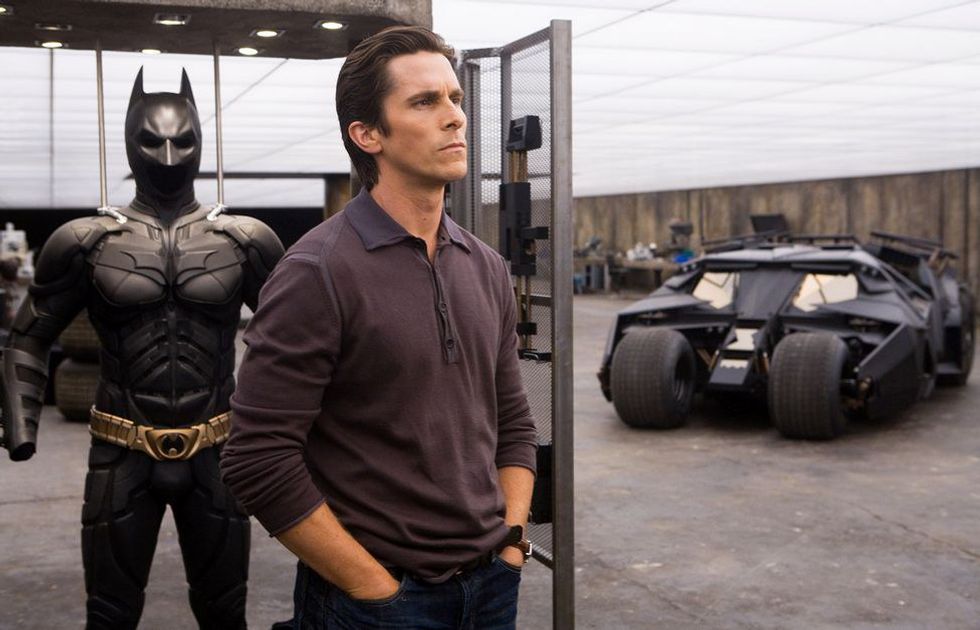

One of the greatest examples of a conflicted hero is tellingly the most popular: Batman. Though, how likeable could someone be who constantly circumvents the law and does whatever he deems fit? In The Dark Knight (2008), district attorney Harvey Dent discusses the necessity of Batman with Bruce Wayne. Playing devil’s advocate, Wayne asks who appointed Batman to be above the law. “We did,” Dent replies, “All of us who stood by and let scum take control of our city” (The Dark Knight 0.20.30). This supports a main theme that the law is not enough and that citizens must take matters into their own hands.

The antihero’s role in superhero myth is to do the job that the morally bound hero is unable to do. Throughout the film, Batman’s ethics are challenged as he must reckon with his own conceptions of right and wrong. The Joker tries to get Batman to believe that even though he strives to protect the law that he is forced to dodge, it might not be in his best interest: “See, their morals; their code is a bad joke, dropped at the first sign of trouble. They’re only as good as the world allows them to be” (The Dark Knight 1.28.32). Why should he protect the city if they are going to hate him for it? Batman is forced to wonder whether Gotham City is worth protecting.

Batman becomes even more conflicted when The Joker gives him an ultimatum: reveal his identity and turn himself in, or hundreds of innocent people will die. Batman considers giving up, but Alfred begs him to endure: “They’ll hate you for it, but that’s the point of Batman. He can be the outcast. He can make the choice that no one else can make” (The Dark Knight 1.10.00). By embracing the hatred of everyone in the city, he can continue to protect them. Batman’s motivations are pure, his internal struggle is humanizing and humbling, and although he cannot save everyone, his actions are just.

In Watchmen and The Dark Knight, the audience is able to step outside of its moral comfort zone and relate to each of the heroes on a personal level. By weighing the actions, motivations, and struggles of the protagonists, the audience is able to understand the necessity of the heroes. By redeeming flawed characters, these films become relevant to moviegoers.

The addition of conflicted heroes and antiheroes to the superhero film genre makes a significant change. Screenwriter Blake Snyder says, “In many a well-told movie, the hero and the bad guy are very often two halves of the same person struggling for supremacy” (Snyder 149). Snyder is speaking metaphorically, but in the conflicted hero or antihero movies, the good and the bad are literally within the same person. The forces of good and evil are struggling for power within the protagonist’s head.

Therefore, instead of the audience rooting for the hero to conquer the villain, they root for the good ideals to conquer the bad, or for understanding to conquer uncertainty. With this in mind, audiences may have a better understanding of where the superhero genre is headed, and consequently, how they can fully enjoy it.