Too borrow a phrase: the rent is too damn high. In 2010, half of all renters spent at least 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities. Twenty-seven percent paid more than half. These numbers have slightly improved since, as a result of the improving economy, but are still far higher than they were just a decade ago. Nowhere is this crisis worse than in San Francisco, where the average cost of annual rent is now $42,144- over half of the average household income there.

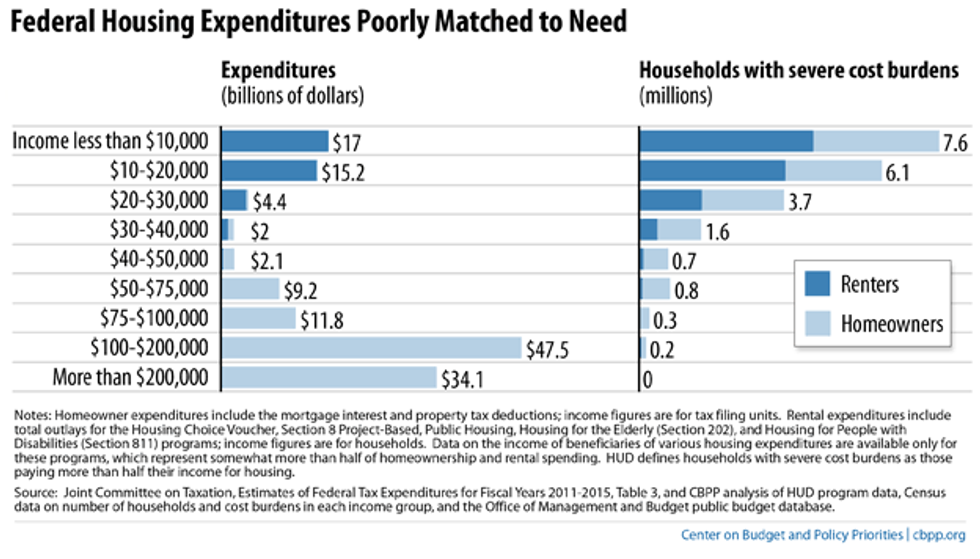

Housing in cities, where more and more Americans are now living, is becoming far too costly for America's poor and middle class. This isn't the shocking part however: it's how the government deals with it. Estimates by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities show that households with incomes greater than $200,000 receive more government housing aid than those with incomes lesser than $20,000 a year- even though the number of people with incomes below $20,000 is four times larger.

Recommended for you

They find that the average household earning more than $200,000 a year receives four times as much in government housing aid as the average household earning less than $20,000. But how is that possible? How could we be spending billions on housing wealthy and upper middle class people who don't need it?

The End of Public Housing

The problem is fundamentally one of an inadequate supply of cheap housing, with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reporting that "only 65 affordable units exist for every 100 extremely low-income renters, and only 39 units are available per 100 extremely low-income renters." This is the result of both a lack of available space in dense areas and regulations on zoning and land use. Loosening these zoning laws can help, but often times it's still necessary to turn to one of two options: either building public housing for those with low incomes, or giving those with low incomes vouchers so that they can afford to live in higher-cost housing.

The United States has historically done both, often with an emphasis on public housing. Starting in the New Deal, this helped in keeping housing affordable for those who lived in urban areas by relieving strains on the low-cost housing supply. By the late 1970's, however, a new way of thinking became dominant in both government and society. This ideology, called neoliberalism, essentially advocated for laissez-faire capitalism in almost every part of society. They believed that government often made problems worse, not better, and sought deregulation, lower taxes, and free trade.

There were plenty of adherents of such an ideology in both parties, though it is best embodied in America by Ronald Reagan. Neoliberals, such as him, viewed public housing as a form of government failure, resulting in lazy and dependent welfare recipients dwelling in buildings which had become plagued by crime and drugs. They believed, in turn, that these public housing projects reduced the property value of the area, further impoverishing others and continuing a cycle of poverty. They sought an end to this. The fight against public housing really began with Nixon, but it was during Reagan's tenure that HUD's assisted housing budget authority was shrunk down to about a third of its 1980 size.

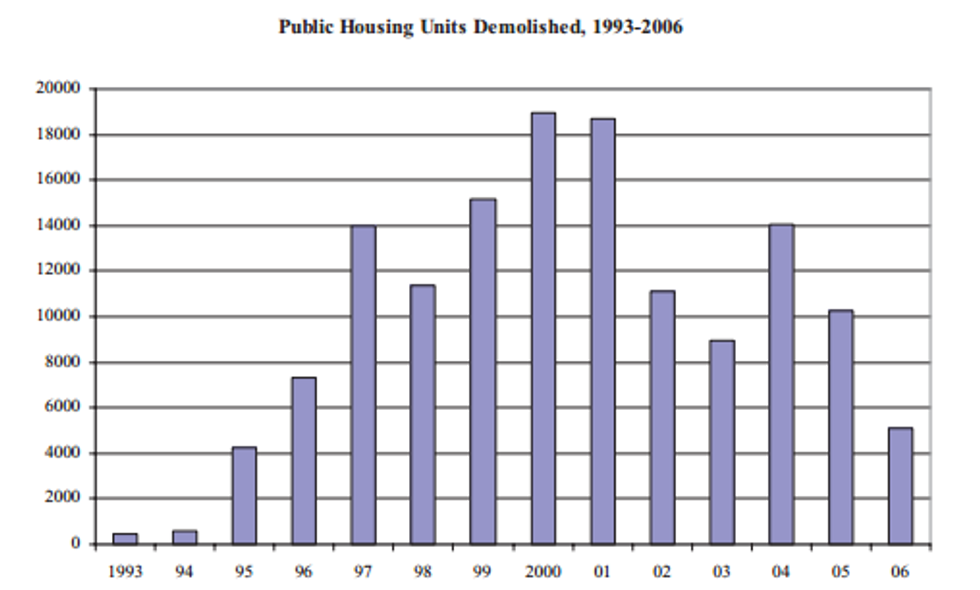

Bill Clinton was the one to bring this legacy to its conclusion. During Clinton's tenure, poor funding had led to increasingly poor living conditions within public housing, making it seem like a failure of a policy and allowing for a swift and powerful campaign to gut it. In 1995, the one-for-one replacement rule that required each demolished public housing unit be replaced by a new one was eliminated, and then permanently repealed three years later. The 1999 Faircloth Limit froze the number of public housing units that could be built with federal funds to its level at that time, preventing new construction even as the population increases and the housing market changes.

Clinton's HOPE VI program, designed to revitalize public housing, eventually "became oriented toward complete demolition and redevelopment" using private investment. It had the effect of "result[ing] in a net loss of housing units that are permanently affordable for very low-income households."

As a result of these policies, the number of available public housing units declined by 140,000 between 1995 and 2007. Furthermore, it was estimated in 2010 that an additional $21 billion was needed to cover the costs of needed repairs and maintenance for public housing, meaning that those units that still exist are significantly underfunded. Today, politicians are perfectly fine with this. The popular opinion of public housing among those now in government is best illustrated by the words of former Memphis Housing and Community Development Director Robert Lipscomb, who in 2009 said: "We’re almost there. We only have a few more sites to go before we can eliminate the words ‘public housing’ from our vocabulary. Wouldn’t that be great?”

Despite these trends, it turns out that the rationale used to justify these policies was all wrong. For example: though some public housing projects were indeed highly violent, there is no evidence to suggest that public housing is inherently tied to crime. In the book "Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy," Fritz Umbach of John Jay College and Alexander Gerould of San Francisco State dedicate a chapter to debunking the myth of public housing creating crime. After reviewing the history of the issue, including a wide breadth of research, they conclude that:

...the simple and frequently invoked idea that "public housing increases crime" is demonstrably false as both an analytic conclusion and a causal model, even as it has proved remarkably powerful as a cultural narrative... Nearly two generations of research on public housing and crime leaves us with this fairly unsatisfying generalization: some public housing seems to have increased crime rates under certain conditions, while other projects, under different conditions, are actually safer than private housing.

As it turns out, the most rigorous research done on the topic also suggests that fears over property value are misplaced, as public housing construction often raises surrounding property values. Looking at New York City's massive program of establishing public housing on primarily "abandoned properties or vacant lots," NYU Public Policy Professor Ingrid Gould Ellen found that"Immediately after completion, prices of properties right next to city-assisted housing sites rose by 8.9 percentage points more than the prices of properties in the surrounding neighborhood," and the benefits only grew more over time. On net, she found that the Section 202 program and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit boosted property value, while the Section 8 and Public Housing programs resulted in "initially negative effects [that] diminish over time." In summary: public housing was not a failure, but it was killed anyways.

Welfare for the Rich

To add insult to injury, even among those public housing units still standing, not all of them are housing those with low incomes. An audit released this Summer found that HUD is allowing more than 22,000 families who are over the income limit to stay in public housing, to the cost of $104.4 million a year. This includes 288 families that are more than $90,000 over the limit. Those 22,000 families may only represent 2.6 percent of all public housing households, but this is far from the only way that those who aren't in real need receive government help in housing.

In fact, while HUD's budget authority was being slashed, housing spending elsewhere was rapidly growing. At the same time that they were cutting public housing for the poor, Reagan, Bush Sr., and Clinton were all trying to promote home-ownership among Americans. Unlike the justification for gutting public housing, the justification for home-ownership was not rooted in neoliberalism, but was instead quite conservative in nature. As Bill Clinton argued in 1995: "You want to reinforce family values in America, encourage two-parent households, get people to stay home? Make it easy for people to own their own homes and enjoy the rewards of family life and see their work rewarded."

Such a drive was largely sold to the American people as a political project to support the middle class. In the same speech mentioned above, during which Clinton was proposing his deregulatory National Homeownership Strategy, he used the term "middle class" four times and the term "American dream" twice. However, when it comes to the tax policies associated with this push, the middle class only reap a small chunk of the benefits, while the wealthy receive the overwhelming majority.

For an example we can look towards the mortgage interest deduction, the largest and most expensive of these tax benefits. In Reagan's grand 1986 tax reform, Congress eliminated interest deductions for everything except home mortgages, which were only capped. This allowed such a deduction to grow "more entrenched with each passing year." Its cost doubled from 1986 to 1996, and then had doubled again by 2010.

In 2013, it was estimated that 71.7 percent of the mortgage interest deduction's benefits went to the richest 20 percent of the nation, 7.6 percent went to the middle group ("the middle class"), and only 0.1 percent went to the poorest 20 percent. Indeed, the top 1 percent benefit more from it than the entire bottom 60 percent. When it comes to promoting home-ownership, it's also a failure. Research shows that it "boosts home-ownership attainment only of higher-income households in less tightly regulated housing markets." But in markets with stronger land use regulations, it actually hurts ownership rates, resulting in "no statistically significant impact on home-ownership" on net.

Depending on what you choose to include, the cost for these types of tax policies is approximately somewhere between $121 billion to $195 billion a year. In either scenario, that's far more than is spent on public housing, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, and Section 8 housing subsidies combined. This is how we, as a nation, were able to find a way to shower the wealthy with billions and billions of dollars for something they surely already have while only providing crumbs to those who don't.

Hiding this welfare spending for the wealthy in the form of tax breaks is a neat little political trick to conceal what is actually happening. Political scientist Suzanne Miller has documented how the government has increasingly been shying away from direct government programs to accomplish its goals, by instead passing complex tax measures to try and accomplish them in a way that draws less public scrutiny. Fiscally speaking, the end results are the same: the government has less money than what it would have had otherwise. The only difference is that, instead of collecting money from people and then giving it back in order to accomplish a goal, the government is now just letting you not give it to them in the first place.

This way, defenders of our current housing policy can deny that any of these tax breaks are "spending" at all, and are instead just a way to let people keep more of their own money. This also allows the government to give its citizens a variety of benefits without actually just giving them welfare directly, an idea that many Americans find repulsive. In a neoliberal society which frowns on government intervention in the economy, people want government help when they need it, but they don't want to acknowledge that it is government help.

But, again, these tax expenditures are no different from government spending. Both involve the government directing money towards a specific use with a certain goal in mind. As Tax Policy Center Editor Henry Gleckman puts it:

Do you have a mortgage? You get assistance. How about employer sponsored health insurance? Or a retirement plan? Do you give to charity? Or buy municipal bonds? Do you own a small business? Congrats. You are being subsidized by the government.

Another Way?

Waging a war on public housing is a fairly easy activity: the direct beneficiaries of it are overwhelmingly poor, and thus have little ability to lobby against cuts and restrictions on the programs. Additionally, as black people rose as a percentage of residents of public housing throughout the middle of the century, it became easier to sell opposition to it to white Americans by using the same subtlety racist tactics that were popular in disparaging welfare. The war on public housing fit, quite neatly, in with the war against "welfare queens," typically portrayed as black women with multiple kids living off of government assistance without working.

But what about tackling the enormous government benefits for the wealthy, like the mortgage interest deduction? Good luck. As one congressional adviser described it, "The mortgage-interest deduction is a sacred cow." David Crowe, Senior Vice President of the lobbying firm National Association of Home Builders, says that his organization "would fight [a repeal of the deduction] to the tooth and nail." And that's not just talk: last year, the real estate industry spent over $95 million on lobbying and had 359 lobbyists that formerly worked for the federal government. There is no anti-poverty lobby with that type of funding or those types of connections.

What would a more sane use of housing funding look like? It's safe to say that it would be one based around helping those who need help the most. This would first mean getting rid of the expensive tax benefits enjoyed by the wealthy by either eliminating them entirely, or reforming them so that they actually benefit the middle class, as they are advertised as doing. Using some of that recovered funding, we could rebuild and revitalize public housing where it's necessary so as to ease supply-side issues, while also creating a federal renter's tax credit to help those with serious cost burdens living in private housing. We could also use it to fund the start-up costs for a universal Housing First program, a highly effective policy program in which every homeless person is given their own place to live. I only say "start-up costs," because there's a plethora of evidence suggesting that such programs more than pay for themselves over time by reducing negative externalities associated with homelessness, like jail and medical costs.

Of course, such a policy shift would provoke enormous backlash from those currently benefiting from the status quo, both industry and individuals. But who said that politics would ever be easy?