If I say “Civil Rights Movement” the first thing that probably comes to mind is Martin Luther King Jr, maybe a famous picture from the March on Washington, or the “I Have a Dream” speech. You might even think about Malcolm X. But if I say James Farmer, you’d probably draw a blank.

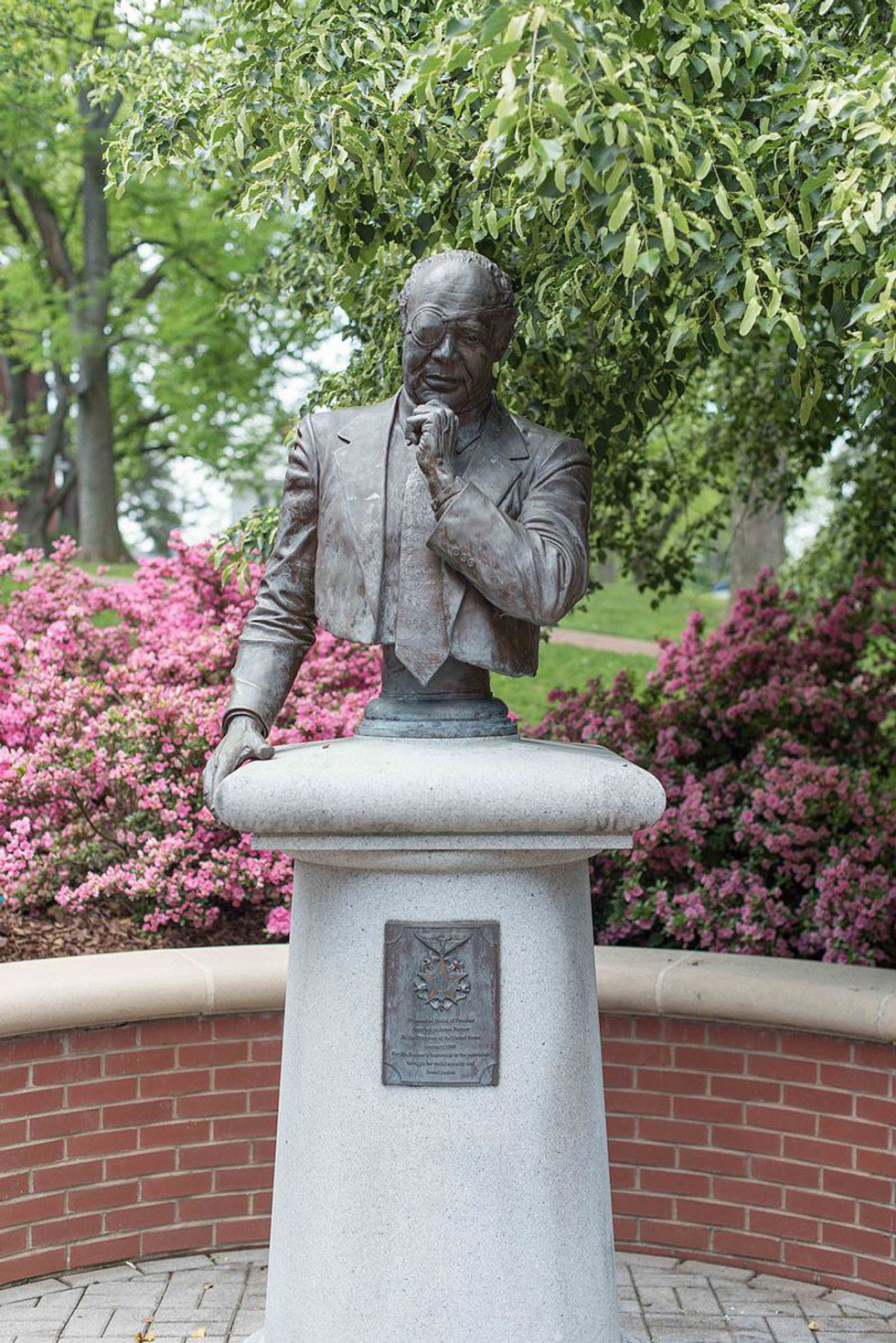

Often left out of history books and Civil Rights Movement lessons, I myself had no idea who Farmer was until I went to college. Here at the University of Mary Washington, we have strong connections to Farmer as he was a professor here. We have a multicultural center named after him, a lecture hall named for him that he lectured in for over a decade, and even his bust outside on Campus Walk. Although I saw his name all over campus I really had no idea who he was until someone told me. Even my African American History Since 1865 class didn’t really mention him when we spent time on the Civil Rights Movement.

So what did Farmer contribute to the movement? Why is he important to the Civil Rights Movement?

Born in 1920 in Texas to a teacher and a preacher, James Leonard Farmer, Jr. excelled in school. In fact, he skipped several grades and started at Wiley College when he was just 14 years old where he joined the debate team. This part of his life was portrayed in the Oprah Winfrey-produced, Denzel Washington-directed movie “The Great Debaters” which followed the story of the debate team at Wiley College. Denzel Washington and Forest Whitaker star in the movie, with Denzel Whitaker (named for Denzel Washington but no relation to Forest Whitaker) plays Farmer.

Although Farmer graduated from Howard University in 1941 with plans to follow in his father’s religious footsteps, he decided to follow Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent philosophies to resist the racial segregation in the United States. Starting during World War II, Farmer put Gandhi’s philosophies to work. At this time, he was living in Chicago working as a television screenwriter and magazine scribe. He also served as a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) director. By this point, Farmer had married and divorced his first wife of only a year. He remarried in 1949 to Lula Petersen and they would be married until her death in 1977.

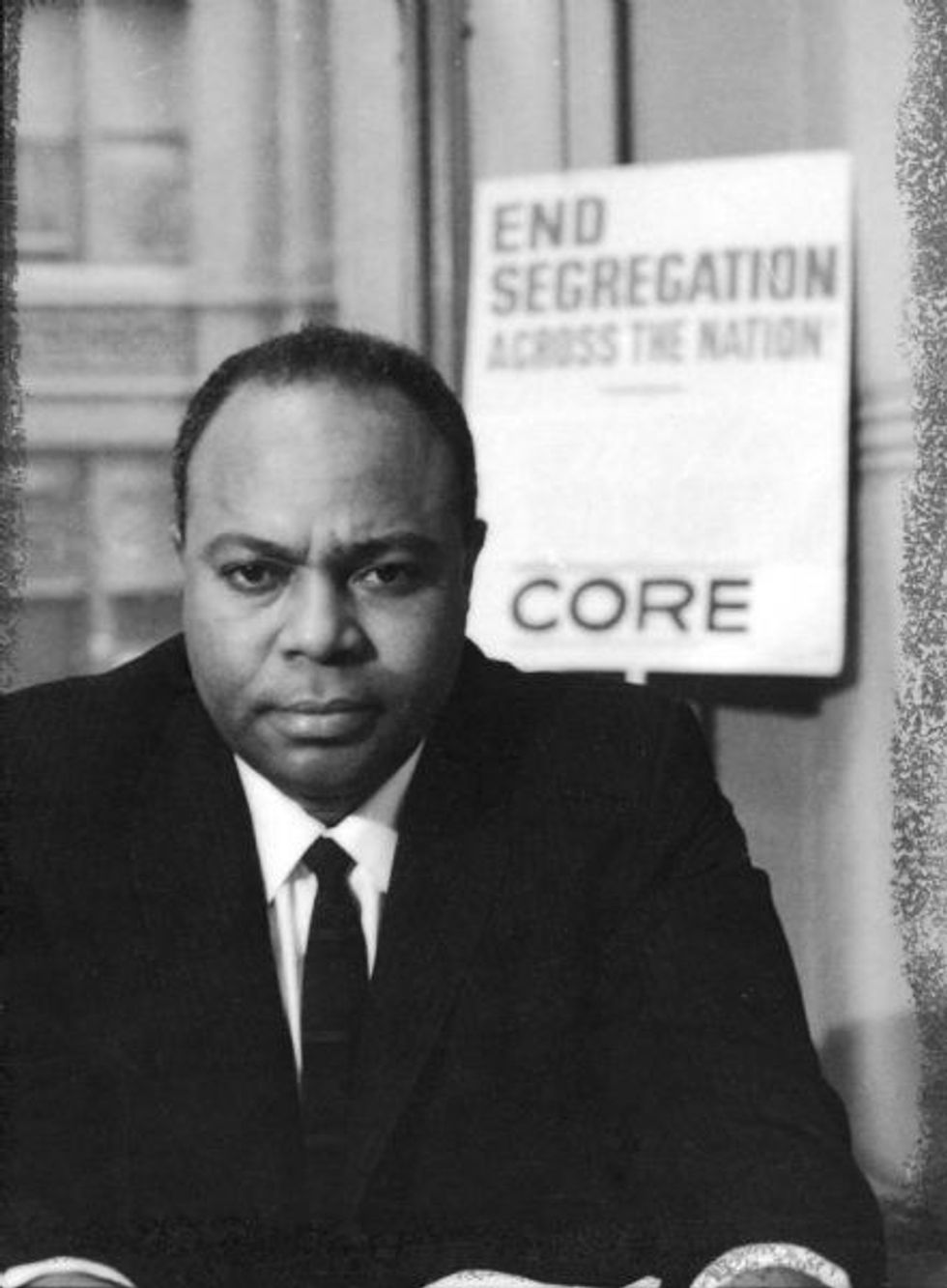

In 1942, Farmer and several colleagues decided to have a sit-in in a Chicago restaurant. Together they formed the Committee of Racial Equality (CORE) which would later be renamed the Congress of Racial Equality with Farmer at the head. Originally CORE had a lot of white Northern members but it became increasingly involved in the South. By early 1961, Famer became the national director. At its highest membership point, CORE had 82,000 members.

Farmer worked on creating the Freedom Rides which CORE had done some work on previously. Challenging segregation on interstate bus travel had been deemed illegal in 1946. Riders were composed of both genders and both white and African Americans who rode on bus routes throughout the South with the first ride beginning in May 1961. The first bus with firebombed in Alabama. Other rides began. Many riders were attacked throughout the rides. One rider was even paralyzed as a result of the attack and many were jailed in Jackson, Mississippi. These attacks and arrests were often televised nationwide, making Americans everywhere aware of the racism still so prevalent in the U.S.

In addition to Freedom Riders, Farmer helped protest the closing of Richmond, VA public schools who were refusing to teach any children. Like other counties, Richmond schools were protesting the Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate public schools. Throughout the South, Farmer and CORE worked to desegregate theaters, pools, bowling alleys, restaurant and other public places.Farmer’s involvement in the movement got him into some trouble in the South. At one point, he was being hunted door-to-door by the Louisiana cops and managed to escape by playing dead in a hearse driven out of the county by a kind funeral home director. The Ku Klux Klan of Louisiana had voted to kill Farmer the next time he stepped foot in the state. Farmer was arrested and jailed for “disturbing the peace” for 40 days, missing Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in August 1963. Farmer had written a speech for the March on Washington that was read by a CORE assistant while Farmer sat in jail.

With the help of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the Interstate Commerce Commission declared segregation of public transportation and stations unacceptable in September of 1961 after only four months of the Freedom Riders. Although this was a victory, it came at a cost. Numerous people had been assaulted or jailed (including leaders such as Farmer) and some even killed, including three CORE members. Farmer considered the desegregation of public transportation the biggest accomplishment of his life.

Farmer resigned from the head of CORE soon after the victorious efforts of the Freedom Riders, citing the increasing differences between his philosophies and theirs. His first book was published in 1961, titled Freedom – When?. After the Freedom Riders, Farmer taught for some time at Lincoln University and ran unsuccessfully as a Liberal backed by the Republican Party for Congress in 1968. When CORE verbally opposed the Vietnam War and called for the troops to be pulled out, Farmer told them not to involve themselves in America’s foreign affairs. He worked under the Nixon administration in the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare but ended up leaving only a year later due to how slowly he felt the national government moved. He published his autobiography, Lay Bare the Heart, in 1985. Over his lifetime, Farmer publish nearly 100 articles in various journals and magazines.

From 1985 – 1998, Farmer served as professor in the History and American Studies department at Mary Washington College (now the University of Mary Washington). On January 15, 1998, Farmer was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President Bill Clinton. By this point, Farmer had been suffering effects of diabetes, including losing his eye sight and his legs. Farmer died on July 9, 1999 at the age of 79 in Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, VA.