Two weeks ago, a musician by the name of Pat “The Bunny” Schneeweis announced that he was done with the punk values of anarchism that had driven him and his music for over 14 years, and so the only honest recourse was to retire from punk-rock entirely. It certainly wasn’t the most dramatic loss that music, or even punk, had suffered in the beginning of 2016; but for a very tightly knit circle, it felt like the loss of an incredibly dear friend. It sounds cliche, but listening to Pat’s music made you feel like you knew the guy, and I think every member of the folk-punk community can recount a memory of when his music touched them most, and which iteration of his career they fell in love with.

I first started discovered his third band, Ramshackle Glory, in the middle of my sophomore year of college. This was a time I distinctly remember being dominated by a sense of disillusionment, anxiety, and loneliness. Around this period, my musical tastes were about as directionless as my moods, so I don’t entirely remember how I first discovered the song “Your Heart Is a Muscle The Size of Your Fist,” but I do remember repeating it four times after the first listening, and having the lyrics memorized by the next day. There was something raw and honest about the song, the singer screamed with pain and desperation, yet the cavalcade of acoustic instruments created a melody of beautiful hope. Every time they sung the chorus, I got goosebumps. One month later, I had the album “Live the Dream” memorized front to back.

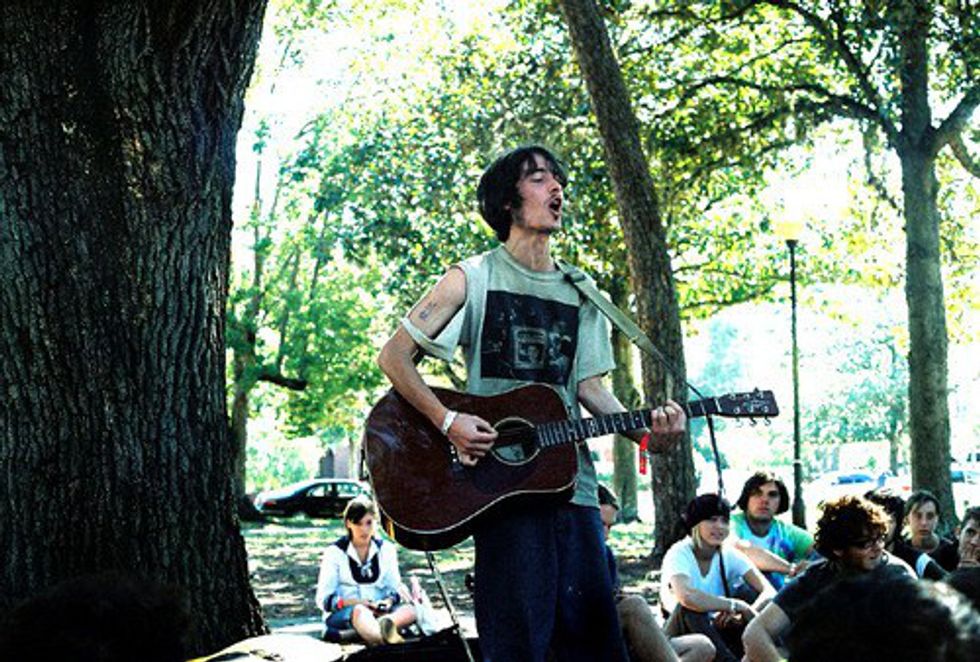

In many ways, it's hard to separate the Pat from his music, because if you look at his discography from start to finish, his musical evolution paints a beautiful story of healing and redemption. He started playing with the group Johnny Hobo & The Frieght Trains, which, despite its ensemble title, sometimes just consisted of Pat playing guitar and a harmonica. As the title might suggest, Pat was largely homeless at this point in his life, as well as in the grips of an addiction to alcohol and heroin. The songs of this period were anthems of self-hate and destruction; a slow-death narrative of drunk-driving, chain-smoking, and angry politics too slurred and incoherent to be properly expressed. All the recordings from this time are harsh and grainy; the lo-fi relics of a man promising to drink himself to death unless sleep came first.

In 2007, Pat formed his next project, Wingnut Dishwasher's Union,and everything started to sound cleaner, and more refined. The sound quality was clearer, the instruments were crisper and more well-tuned, and there was more experimentation with electric and acoustic instruments, giving the sense of intentional musicianship, rather than just playing with whatever was on hand. The politics started to become more coherent as well, creating fantasies of freedom and happiness, rather than just destruction and pain. His anarchism became more of a quest for allies, rather than a self-imposed isolation. Most importantly, the pure self-hatred had dissipated, and been replaced with a desperation to find some sort of happiness.

In 2009, Wingnut Dishwasher's Union broke up, and Pat entered a rehabilitation program. Two years later, he reemerged in the punk community, completely abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and announced he would be forming a new act, Ramshackle Glory. One year later, they released their debut album "Live to the Dream," which I proudly stand and call my favorite punk album of all time. It’s an apocalyptic dovetail into the mind of someone who’s just seen some light at the end of a very dark tunnel, and has tried to take stock of everything that makes life worth living. By its midpoint, politics, religion, philosophy, drugs, alcohol, and love have all been put on the table and dissected meticulously. Songs like "Bitter Old Man" and "From Here to Utopia" make me fall back and re-assess the most basic tenants of why I’m on this earth, asking questions like “If freedom means doing what we want, don’t we gotta want something?” “We Are All Compost in Training” and “Never Coming Home” are two of the most heartbreaking tunes I’ve ever heard - tales of guilt and despair that question what it really means to hurt someone, and just how impossible forgiveness sometimes is. And yet, for all its sadness and nihilism, the album concludes with two of the most amazing tracks of hope – “Your Heart Is A Muscle the Size of Your Fist” and “First Song, Part 2.” – which build momentum before leading to the climactic line of the entire collection, a line that still gives me shivers; “But I try to have faith in the things that will happen, I get saved from myself when I do, so maybe 'god' isn’t the right word, but I believe in you.”

I realize that I’ve gone on and told the guy's life story (and there’s much more to it, don’t get me wrong) but I think it’s important to try to give all of this context to really express how much his decision to give up on punk hits hard. He gave a detailed explanation of his retirement with the release of his latest split with the Connecticut-based rapper, Caschi. The piece almost reads like a eulogy of his former self, as he describes just how much his music was dependent on both his journey towards redemption, and the proud political beliefs that had gotten him through this period.

A few years ago, in an interview with the radio show "A Fistful Of Vinyl," he’d described how he couldn’t play the songs from the Johnny Hobo and Wingnut Dishwasher days, because they were so closely entrenched in his experience of being an addict. In a lot of ways, his decision to stop playing punk is a similar choice, based on his inability to continue believing in the staunch anarchism that had previously marked his music.

Yet, it’s strange to consider both him and his songs this way; to conceive that the mindset that created the music I treasure, was probably something he was desperate to escape. In his own farewell, he wrote,

“I have grown into a basically ordinary person, albeit a somewhat strange one. Nothing I write feels very skilled at communicating whatever it is I am trying to say, but it just seems important to tell you that I am not really an anarchist or a punk anymore. My viewpoint has changed dramatically in the last six to nine months, and this kind of politics and music is just not where my heart is anymore. I have no interest in convincing anyone of anything, so that's all that's important to say about it. I just don't want people to feel tricked when they buy or listen to my music.”

On one level, there’s a beautiful honesty to this decision, a refusal to create art unless he fully stands behind what he’s saying. And yet, there’s just a very bitter-sweetness to knowing that the sorrow that had inspired some of the most powerful music I’ve ever heard, has finally been lifted. It’s as if, by watching someone’s process of healing, we started to fall in love with the disease, rather than the cure.

Folk-punk neither begins, nor ends, with Pat. There are countless acts that have all approached ideas of redemption, freedom, and anarchism, in immensely unique ways (Mischief Brew, Days N Daze, Andrew Jackson Jihad, Cottontail – just to name a tiny few), and phenomenal new acts are constantly popping up in DIY punk communities on Reddit and Facebook. Yet, it’s still impossible to pretend that Pat hasn’t stood as one of the most influential figures in the genre’s history, as young as it may be. Type his name on Google and you'll be bombarded by photos of his lyrics tattooed on arms, and with stories of hearts healed and lives saved.

It’s easy to consider Pat’s retirement a loss, and yet there is another way of looking at it. It stands as a beautiful conclusion to a hard, yet beautiful, saga. I hope that in spite of all its moments of misery, his long musical journey has brought him to a point of peace and happiness. I can definitely say it’s done the same for me, and countless other listeners.