For most of the 21st century, Mexico's narco problem has been misinterpreted by outsiders as a mere criminal issue that needs to be dealt with internally. However, the lack of understanding of the development and structural workings of the drug industry in Mexico has been one of the reasons why it has grown into the national and international threat that it is today. Mexico's transition to neoliberalism and democratic policies set the right circumstances and path for Mexico to become the complex Narco-state that rules the streets today and the government tomorrow.

In the post-revolutionary war era, Mexico turned its head towards neoliberalism in an attempt to solve their economic issues. Mexico attempted to reform the state and fix the issues that lingered after the revolutionary war. The country was left in debt and while the government scrambled to stay afloat, outside nations were circling like sharks, waiting for them to drown. That is when the government started to adopt neoliberalist reforms. Neoliberalism "enshrined competition, favored free trade as the natural response to the new global economy, and argued that corporations should be given greater independence."[1] These policies also caused an increase in urbanization and the middle class. However, it inadvertently damaged the standard of living for the working class and the peasantry. More specifically, the neoliberal reform depleted the rural and agrarian economy. There was an increase in poverty in the countryside and it widened the income inequality gap. [2] All these issues heightened the discontent among the citizenry and boosted the number of uprisings and movements within the 20th century. As a result, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or PRI, grew as an authoritarian state in order to squash these uprisings.

Corruption and income inequality were just some of the issues that incited citizens to demand change. One prime example of the demand and forceful response from the government was the 1968 student movement and the Tlatelolco Massacre. As Mexico prepared to host the 1968 summer games, the government pushed for the "construction of athletic facilities, hotels, housing projects, tourist projects, and a new modern subway system… despite budgetary uncertainty."[3] Different factions had varying demands, but the overall sentiment of the movement was that the government was pouring so much money into the Olympics in order to hide all the nation's problems. There were several riots throughout 1968, however, the tension came to a peak on October 2 when there was a "rally at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the district of Tlatelolco in order to criticize the government for its failure to comply with their earlier demands."[4] When the police and army arrived at the rally and the protesters refused to disband, the shooting began and chaos took over. Although there was no official number of deaths or details of what happened that night—this night would be remembered in history. The forceful squashing of uprisings signaled an authoritarian and corrupt nation that the citizens were no longer willing to swallow.

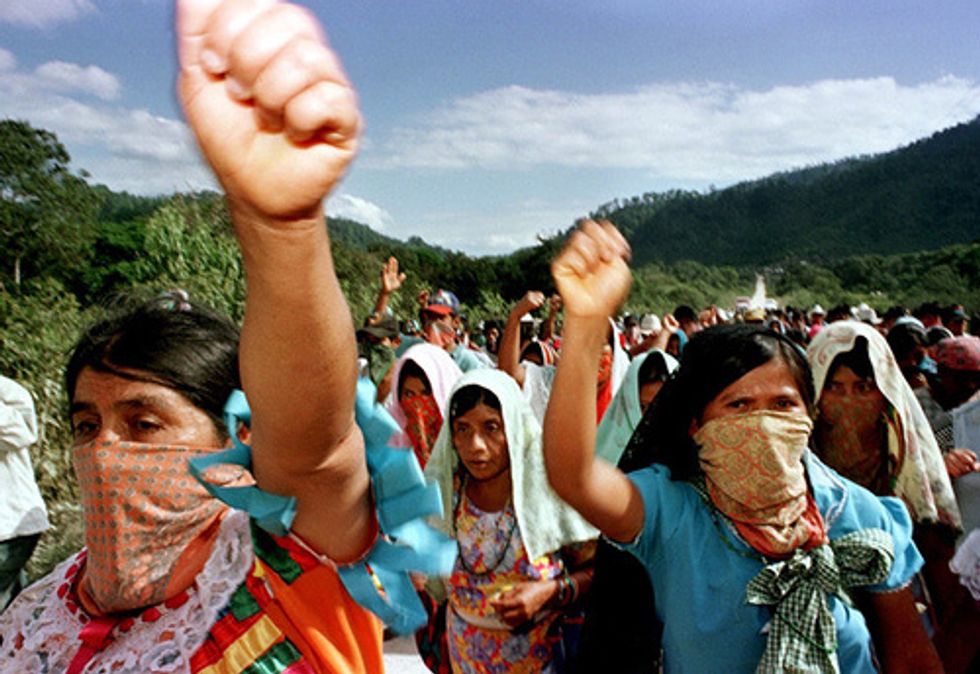

The final nail on the PRI's coffin was hammered by the popular pressure that was illustrated by the 1994 Zapatista Uprising. With the neoliberalist agenda in the home front, the government was ready to ratify NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement. NAFTA was seen as a death threat to the indigenous people because it would beat them out of their local agricultural business. This only poured lemon on already sour wounds. The indigenous people had already been targeted by the reform of Article 27 which divided and sol indigenous land to foreign entities. The Zapatista Movement was formed from these grievances by the indigenous people. On January 1, 1994, the Zapatistas declared war on the government and demanded better rights. Some of their demands included an end to NAFTA, the repeal of Article 27, and autonomy for the indigenous people. Although the uprising was shut down, the movement highlighted the social unrest that was overtaking the country.

This discontent paved a path for democracy and a government that would not rule with an iron fist and would put Mexican people first. President Ernesto Zedillo, the last PRI president, was devoted to allowing a democratic government to take over the wheel, and ultimately helped lead the downfall of the PRI's 71-year rule. "Mexico's federal electoral institute gained autonomy in 1996, and the PRI lost its majority in Congress in 1997… [which made it] harder to fix an election, even if the PRI wanted to."[5] The 21st century opened with Mexico's first democratic president, Vicente Fox, under the Partido Acción Nacional, or PAN. "The optimism that accompanied Mexico's transition to democracy in electoral terms slowly eroded over the course of the Fox presidency because of his failure to deliver on campaign promises, especially those related to economic reform."[6] Fox often found himself battling internal tensions within his party and controversial moves and policies. Several controversies, including the one involving his own wife "siphoning funds from the National Lottery," [7] brought light onto the fact that corruption and economic issues were still at large within Mexico. This rocky transition to democracy did not bring forth the hopeful goals that the citizens had for their government and it inevitably set forth the right conditions for a Narco-state to develop.

`The transition to democracy delayed a forceful approach to eradicate the drug trafficking issue in Mexico because of the ghostly presence of the PRI. Firstly, to sustain the support of the citizens, there was a focus on "ongoing investigations into the PRI's old dirty war."[8] Additionally, afraid to appear too much like the authoritarian PRI, Vicente Fox had no clear direction on the drug issue in Mexico, and when resistance surfaced, he did not fight hard enough against Congress or for arrests in order to prevent further criticism.[9] Furthermore, with the demise of the PRI, the iron fist policing was no longer available and the new democratic successors were not willing to follow their predecessor's mistakes. This was first seen "on January 21, 2001, [when] arch-mafioso Chapo Guzman escaped from a high-security prison in Guadalajara" with the help of two security guards.[10] He was captured again in 2014, thirteen years after his escape; this illustrated how weak the police system was. Although the following presidency marked an escalation and militarization on the war on drugs, Felipe Calderon's delayed response only allowed el Narco to grow into the monster that it is. By the time actual measures were taken, the drug industry had enough time and resources to become Hydra, the mythological creature that grows two heads when one is cut off. The killing of Arturo Beltrán Leyva, alias the Beard, is a perfect example of the effect that the government's delayed response had because it only incited "local mafias to try to seize Beltrán Leyva's lucrative territories, spreading the war from the Sinaloan empire of the northwest to Mexico's center and south."[11] By the time more tactical action was taken, it only incited more violence and war on the streets.

The combination of neoliberalism with democracy created the perfect conditions for the Narco-state to develop into what is known today. Neoliberalism illustrated the social discontent that lived among Mexico's streets. This public pressure allowed for democracy to be an optimistic change; however, the first six years did not bring the alleviation that the public hoped for. Also, compared to the authoritarian PRI, the democratic government was not able to provide a strong policing system to fight in the beginning stages of the drug trafficking industry. It allowed for drug traffickers to bribe the police, and by the time arrests started to happen, they "did not subdue violence, but only inflamed it"[12] because it was helping one cartel over its rival. This incited people to join drug trafficking. Arturo Guzmán Decena is a prime example; he went from a special forces commander to a narco killer because "he was tempted by the glitter gold, seeing ostentatious gangsters earn more in a year than many professional soldiers in a lifetime," and "the move to democracy made many in the army nervous about their place in the new Mexico."[13] The neoliberalist ideals also created straight paths between Mexico and the United States. It pushed the economic focus on the northern border states, which increased the cross-border trade. This increase in cross-border trade created the paths that the cartels would later fight over to control cross-border drug trafficking access. These expanded the drug industry and the turf war among cartels. All in all, this is not to say that neoliberalism and democracy cause drug trafficking, but that in this case, they were implemented at the right time, creating the perfect storm for the worst monster.

With the perfect circumstances, the Narco-state developed into a complex criminal insurgency that creates crime at the highest rates for the highest economic reasons. At this point, whether the kingpins want it or not, their power is expanding to become a political governing entity. The case of the 43 is a perfect example of this. On September 26, 2014, "nearly 100 Ayotzinapa students" were on their way to commemorate the Tlatelolco Massacre, when at Iguala, they were stopped and shot at by local police, and 43 students were taken, never to be seen alive again. Throughout the investigation, it came to be evident that political entities, like the mayor and even the state governor, were somehow involved in the disappearance or cover-up. Several other entities, like the forensic team and the army, did not do their job or they did it incorrectly and messed with the investigation. "A selection of military records… indicated that the military was aware of some of what was happening and did not intervene." At least one gang has been linked with the case, Guerreros Unidos, and Los Rojos might also have some kind of involvement.[14] This web of involvement makes it difficult to differentiate between the government and the cartel (including those that are under the payroll of cartels). They are so convoluted, that they start to become to look like one entity. That is why El Narco is so powerful and why it poses a national, and even international, threat. El Narco is very easily becoming the government whether that is its intention or not.

Mexico's transition to neoliberalism and democracy set the right stage for the complex Narco-state to be developed. Its complexity and brutality have given el Narco incredible power that it is starting to become a governing entity. Although this is an issue in Mexico, it is so pervasive that it has global tentacles, and unless, there is an understanding of where it came from and how it works, it will continue to devour innocent lives and spread like a pandemic.

[1] Susan M. Deeds, Michael C. Meyer, and William I. Sherman. The Course of Mexican History (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 535.

[2] Deeds, et al, 537-542.

[3] Deeds, et al, 490- 491.

[4] Deeds, et al, 492.

[5] Ioan Grillo. El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal Insurgency (New York/London: Bloomsbury Press, 2012), 91.

[6] Deeds, et al, 546.

[7] Deeds, et al, 547.

[8] Grillo, 93.

[9] Grillo, 91.

[10] Grillo, 92.

[11] Grillo, 127.

[12] Grillo, 104.

[13] Grillo, 97.

[14] Ryan Devereaux. "Ghosts of Iguala: Mexico: How 43 Students Disappeared in the Night," The Intercept, parts 1 and 2 (2015).