In my previous article, I discussed broadly how mythologies express a culture’s beliefs about their relationship to one another and with God. Through our common biology as human beings, we share similar desires for relationships with each other, but also with God; these desires get expressed through stories about our creation, which develop into mythologies. Throughout the world, cultures have had similar stories that they tell, stories with patterns that express the underlying truths about us as humans. One of these stories that is common to a great portion of the world is the story of the human need for redemption by a savior. This common story is obviously played out in Christianity, and because of this, critics have argued that Christianity is just another one of these myths that countless other cultures have told. I, however, wish to discuss how the Christian story is distinct from these other stories, and show that the pattern that develops across the world is not cause for doubt, but evidence for its truth.

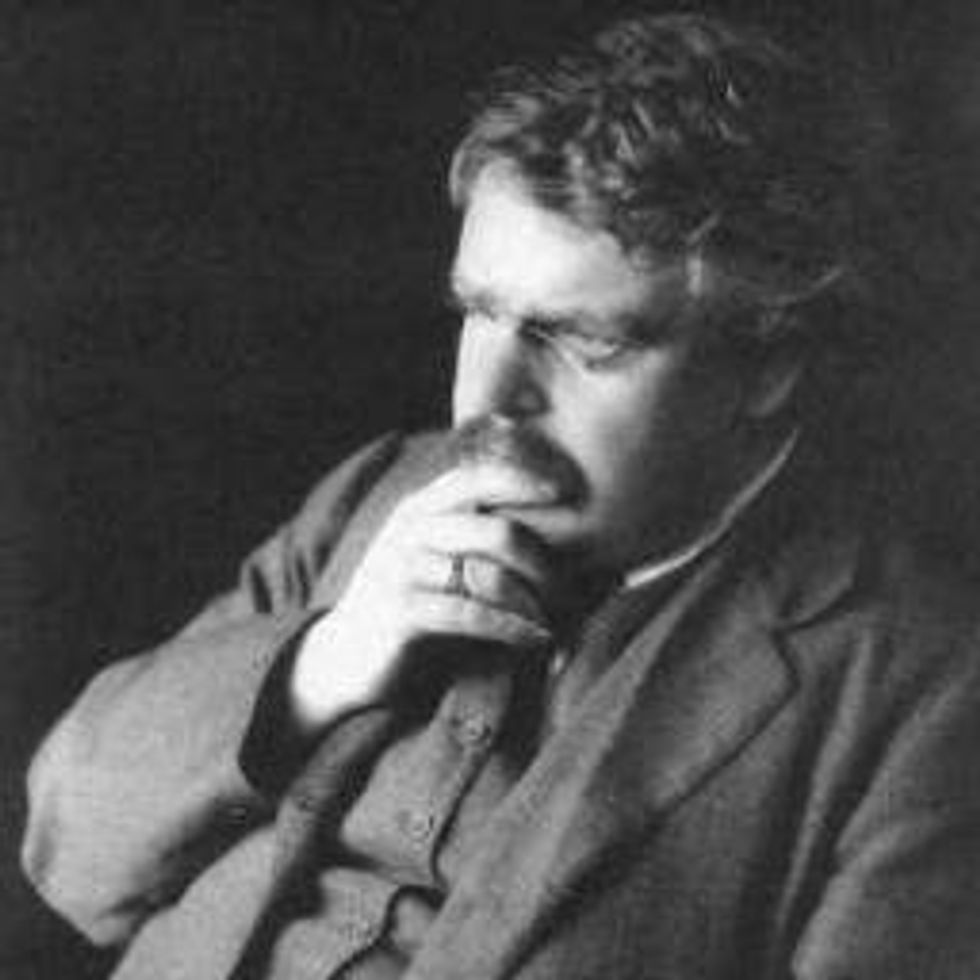

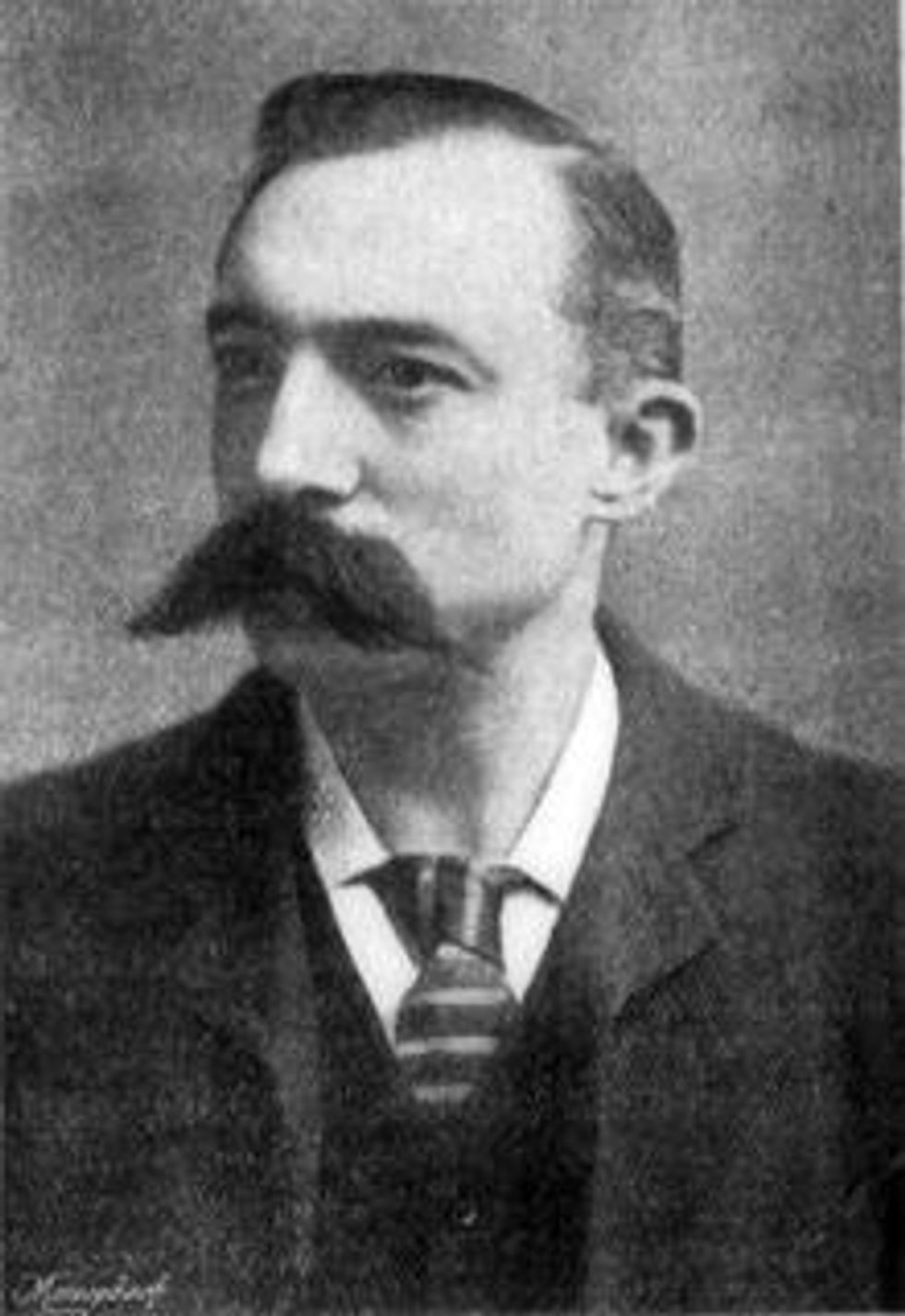

G. K. Chesterton, Catholic writer and cultural critic, expresses this idea in a powerful way in his series of articles, later referred to as the “Blatchford Controversy.” In 1904, a series of articles were published in the Clarion newspaper by various Christian writers defending the faith from the attacks of Robert Blatchford, editor of the newspaper. Blatchford, possibly trying to be fair and open-minded, or perhaps overconfident in his ability to defend the anti-Christian position, allowed this group of writers to defend their faith freely and without constraint in his newspaper. Among them was the clever 30-year-old, Gilbert K. Chesterton.

Chesterton had for the previous year been involved in a controversy with Blatchford, writing letters and articles in the Daily News and the Commonwealth defending Christianity and attacking the heresies Blatchford supported, such as determinism and materialism. Chesterton in “Christianity and Rationalism,” one of the articles, wrote that humanity has a tendency to get caught up in things that simply do not matter. A German professor who has “found the four hundredth accurate origin of protoplasm,” he says, is similar to the savage who paints his face to please “the ghosts (or what not)”—they are caught up in vain matters, “falling under the influence of that starry impulse which leads men to take a vast deal of trouble about quite useless things.”

Put simply, humans get distracted. Especially in the modern day, we are constantly being drawn to vain and useless matters such as mindlessly browsing Facebook, Twitter or any other social media. Back in Chesterton’s day I am sure there were a fair share of distractions, but Chesterton points out something interesting: even amongst all the distractions of his day and our day, there is something that draws us to true meaning. To Chesterton, this is Christianity.

Chesterton cleverly pointed out that some of the most intense interest in Christianity comes from those who consider it a “fraud,” though he does not blame them “for having discussed it at great length; since the subject [of Christianity] is the nature of the Universe, it is necessarily as large as the Universe, and as rich as the Universe, and, I may add, as amusing as the Universe.” Here Chesterton shows that no matter one’s views on Christianity, it has a universal draw—that even the most vehement opponents inevitably find it intriguing. Chesterton seems to think this is so because of “Christian joyousness,” writing, “Christianity is itself so jolly a thing that it fills the possessor of it with a certain silly exuberance, which sad and high-minded Rationalists might reasonably mistake for mere buffoonery and blasphemy.”Contrary to what many non-Christians believe, Christians are not sad, restricted, or controlled by the Church. They are free to be joyful in the face of evil and sin because of Christ’s redeeming sacrifice. This, I argue, is what gives Christianity a universal intrigue, and is what is expressed by the stories in the Bible.

On another occasion, Chesterton delves into Mr. Blatchford’s book, God and My Neighbor, and shows that Blatchford’s arguments against Christianity, in some cases, are Chesterton’s own arguments for Christianity. Chesterton here delves into the center of the pattern of the human expression of inner desires through stories and myths. Chesterton wrote,

“Mr. Blatchford and his school point out that there are many myths parallel to the Christian story; that there were Pagan Christs, and Red Indian Incarnations, and Patagonian Crucifixions, for all I know or care. But does not Mr. Blatchford see the other side of this fact? If the Christian God really made this human race, would not the human race tend to rumors and perversions of the Christian God? If the center of our life is a certain fact, would not people far from the center have a muddled version of that fact? If we are so made that a Son of God must deliver us, is it odd that Patagonians should dream of a Son of God?”

We are made in the image of God. We are created to love God and to be loved by God, so is it really unfathomable that human communities throughout time have been drawn to a Redeemer, a Son of God, a Messiah, to come to liberate them from evil and set them free? These myths and stories from communities all around the world reflect Truth. Though they specifically may not be Truth, they reflect the Truth of Christianity.

This is an idea that Chesterton explores on a far deeper level in his book, The Everlasting Man. In it, he shows that Christ is the center of all history, and that stories, myths, and literature from all around the world recall the truths of Christianity and reflects the mystery of Christ. It may well be the case that, despite Blatchford’s arguments, the frequent repetition of Christian themes and messages from cultures and religions all around the world actually legitimizes Christianity. It shows that throughout all history, humankind has been drawn to the truths expressed by Christianity, though they themselves do not express them fully or entirely accurately. It is only with the coming of Christ that these other myths and stories are completed, clarified, and fulfilled, and, in the Christian community, are expounded upon further. As Chesterton writes, “The Blatchfordian position really amounts to this—that because a certain thing has impressed millions of different people as likely or necessary, therefore it cannot be true.”

To drive home the point, Chesterton adds:

“The story of Christ is very common in legend and literature. So is the story of two lovers parted by Fate. So is the story of two friends killing each other for a woman. But will it seriously be maintained that, because these two stories are common as legends, therefore no two friends were ever separated by love or no two lovers by circumstances? It is tolerably plain, surely, that these two stories are common because the situation is an intensely probable and human one, because our nature is so built as to make them almost inevitable.”

Chesterton argues that spiritual truths will inevitably manifest themselves throughout history in story and legend. Because we are all implicitly drawn to Christ, it is no wonder that, in all cultures around the world, our most cherished stories and legends so often depict a Redeemer, a Messiah, a Son of God.

Billions of people today consider Christianity true and necessary. Throughout the world, Christians and non-Christians alike have reflected its truths in stories and legends. Blatchford must have had a low view of humanity or an extremely high view of himself to think this a reason for the falseness of Christianity. It is the abundance of stories and myths of a Savior and Redeemer throughout the world that give credence to the truth of humanities need to be saved. Stories, which later become myths, are the perfect avenue for expression of the need, coming from a deep spiritual and emotional place within us all.