At about this time, each year, thespians of all ages are entering their first days of school. Whether you have preconceived notions of a certain acting technique, you are still likely to be exposed to it in class, even if you hate it.

Firstly, it's good for an actor to know what techniques are out there and available. Even if a particular method does not work for you, it works for someone else out there, perhaps someone with whom you may have to work during your career, and it is good for you to understand how your fellow cast-mates like to work.

If you are going to school with little to no background knowledge of the various acting practices out there, that's okay too. All you should do at this point is to keep an open mind about what you are learning. Try some of everything to see what works for you. A good drama school should supply you with a plethora of options: Stanislavsky, Meisner, Adler, Strasberg, Uta Hagen, RSC, Commedia Dell'Arte, Arthur Lessac, and the list goes on.

Now, in the theatre world, there is a great schism between Lee Strasberg's "Method" and Constantin Stanislavsky's "system." Some actors mix them up and confuse them for each other or the same, and some actors strongly favor one over the other, seemingly loathing those who practice the opposite technique.

Personally, I believe that whatever works best for an actor is what should be used, but I do not believe that they are "equally affective," for lack of better words.

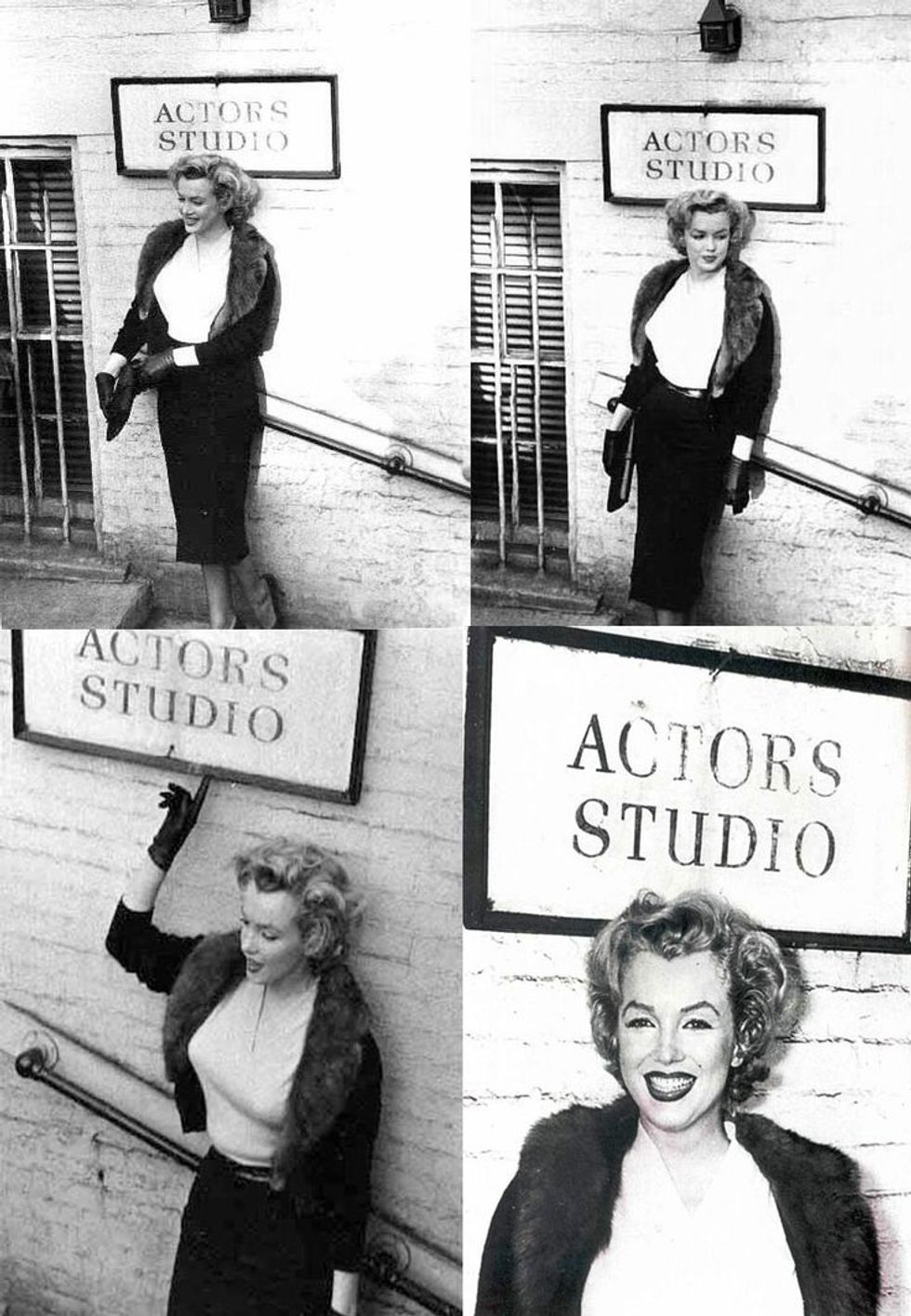

Here's some background information, for those who are not familiar with the two techniques: Stanislavsky, as the Father of Modern Acting, introduced some of the first techniques for actors to learn how to act. One of his methods included something called affective memory, which has since been molded and morphed into the terms "emotion[al] memory" and "emotional recall." In this practice, actors use a repertoire of their personal memories to evoke their character's emotions, like being so moved that they need to produce tears. Strasberg adopted this, and many other, techniques from Stanislavsky. Unfortunately, because affective memory requires an actor to constantly be reminded of their past, in often negative ways, the mental hygiene of an actor who practiced it worsened. Furthermore, the technique distracts the actor out of the scene and into his personal life. In the end, Stanislavsky decided to drop affective memory from his teachings, but when Strasberg learned of this, he decided to continue it as part of his school, the Actor's Studio.

My recommendation is to begin with Stanislavsky's system. He sought to find the very basics of an actor's approach to a character and stage performance, breaking it down into four parts: relaxation, concentration, communion, and commitment. His focus was using action to drive the natural responses of an actor, so when in a scene, the actor should push for an outward sense of observation, finding more concern in trying to understand his scene partners and surroundings than on his own character's thoughts and emotional reactions. Stanislavsky's main goal was to achieve a system that would produce genuine and natural performances.

If you are one who prefers to have a planed performance, down to the very detail of thoughts and actions, then you may want to try Strasberg's Method. His goal was to produce a method of acting that would produce repeatable and consistent performances. His focus was on an actor's awareness of self and on his character's development, which is how some actors became famous for living their roles. That's not to say that astounding performances have not come from these Method Actors, but they do have a reputation for going to the extremes to prepare for their roles, including unnecessarily risking their health. Some actors argue that much of their work is unnecessary for preparing their role; I mean, did Mr. Day-Lewis really need to build the set in order to play Mr. Proctor in The Crucible? That's not to say that astounding performances have not come from these Method Actors, but they do have a reputation for going to the extremes to prepare for their roles, including unnecessarily risking their health. Even so, not all Method Actors need to use affective memory or the other health-hazardous techniques. Strasberg, branching off from Stanislavsky's teachings, also adopted relaxation and concentration. His bit on action differed from Stanislavsky's, though, in that it focused on the actor's sense of reality and his reactions to that reality.

Again, every actor should just pick and choose what pieces of the various techniques work best for him. These two techniques are simply two of the most widely known and most commonly practiced techniques. Be warned, though, that are some very strong advocates both for and against Strasberg's Method.

No technique may be deemed right, nor may it be deemed wrong. It is simply a taste of preference, and thankfully there are dozens of other techniques out there to supplement the teachings of both Stanislavsky and Strasberg and hone your talents.