As a writer, it is always my goal to create ‘professional’ pieces, as untouched by my own personal biases as possible. But, this week, with this article, I can’t do it.

Over the last few days, #MeToo has saturated Facebook and other social media platforms. The hashtag is meant to “give a sense of the magnitude of the problem [sexual assault and harassment].”

Though the hashtag’s creation and prominence is credited to actress Alyssa Milano, its true originator is Tarana Burke, founder of the youth organization, Just Be Inc. It was this Black woman that created the “Me Too” campaign 10 years ago.

Burke describes the inception of the movement as coming from “the deepest, darkest place in [her] soul.” Struggling with her own trauma, she could not find it in her to support a young girl confiding in her about being assaulted at the hands of her mother’s boyfriend.

"I will never forget the look because I think about her all of the time. The shock of being rejected, the pain of opening a wound only to have it abruptly forced closed again — it was all on her face. And as much as I love children, as much as I cared about that child, I could not find the courage that she had found. I could not muster the energy to tell her that I understood, that I connected, that I could feel her pain. I couldn't help her release her shame, or impress upon her that nothing that happened to her was her fault. I could not find the strength to say out loud the words that were ringing in my head over and over again as she tried to tell me what she had endured… I watched her walk away from me as she tried to recapture her secrets and tuck them back into their hiding place. I watched her put her mask back on and go back into the world like she was all alone and I couldn’t even bring myself to whisper…me too."

“It wasn’t built to be a viral campaign or a hashtag that is here today and forgotten tomorrow,” Burke said in an interview with Ebony magazine. “It was a catchphrase to be used from survivor to survivor to let folks know that they were not alone and that a movement for radical healing was happening and possible.”

However, that does not mean Burke doesn't recognize the power of #MeToo and the voice it has given to so many. It is a slippery slope to erasure, as Black women, and other women of color, are too frequently isolated from the conversations they themselves have started.

No movement, no issue, no campaign is above critique, even the best of them. Remember that.

Criticism aside, the hashtag has gone viral for a reason — folks are using it to express the frustration, the anger, the pain, sadness, and hurt that is matted with sexual assault.

Statuses may bear just those two sobering words, carrying with them the weight of a story (or many!) untold.

Or, they are a preface for a person’s experience with assault or harassment, shared with the world graciously and courageously.

It is inspiring to witness the many brave individuals willing to open up about something so painfully intimate. But, simultaneously, it so terribly tragic to know each of these people has survived such unimaginable violence.

For me, it is especially heart-wrenching because I know there are countless who wish to stay hidden and silent as a (valid) means of self-preservation and self-care. I know they far outnumber the floods of people who have chosen to be seen.

Of every 1,000 sexual assaults, less than 350 are reported to law enforcement, meaning two out of every three incidents go unreported. Why? Too many reasons.

RAINN, the Rape Abuse & Incest National Network, shines light on some of the reasons for not reporting:

- 20% feared retaliation

- 13% believed the police would not do anything to help

- 13% believed it was a personal matter

- 8% reported to a different official

- 8% believed it was not important enough to report

- 7% did not want to get the perpetrator in trouble

- 2% believed the police could not do anything to help

- 30% gave another reason or did not cite one reason

TW: sexual assault; sexual harassment.

I am a part of the 8% who believed it was not important enough to report my sexual assaults. I have never shared my experiences and I have never even entertained the thought of reporting them. I have struggled, stumbled, and stalled in trying to process and cope with all that has happened to me.

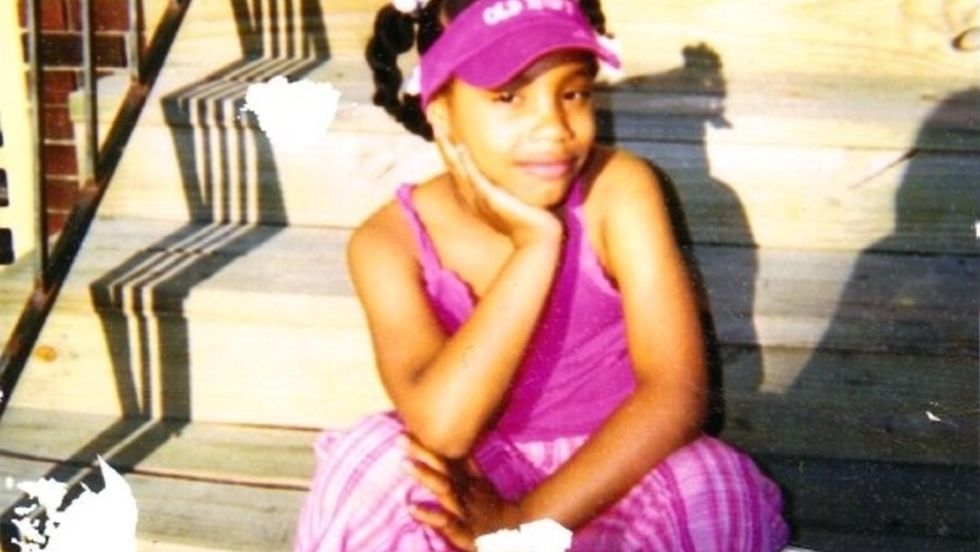

My body has never been mine; I think that is the best way to prelude my own story.

I began to develop breasts at the age of 7, in second grade. In the fifth grade, at 10 years old, I had my first menstrual cycle. But before then, before the periods, before the training bra, I remember the uneasiness, the looks, and the lingering touches, all from different, but familiar familial hands.

I remember waking up in the middle of the night with my underwear down. And trying, desperately, to go back to sleep. I would try to steady my breathing — couldn’t let them know I was awake, I was aware — and I would lay there, motionless, while this person violated and molested my prepubescent body. When they were done, I would feel my underwear yanked back up into place.

One night, I awoke again to my underwear below my knees, and I silently pleaded with this person to stop. And, they did. But not because they could somehow hear me begging and not because they suddenly realized what they were doing was immoral, degrading, and illegal.

No, he stopped because he heard an adult coming up the stairs to peek into the room we all slept in.

I don’t remember how many nights this happened. I don’t know how many times I slept through this, either. It comforts me, though, to not remember. Memories like those are burdens that I do not wish to carry.

I was 11 years old, walking home, and was approached by a man, maybe in his early 30s, on the street. He beckoned me, asked me my age and, cautiously, I told him.

“Damn!” he sighed, “You too fine to be that young.” He looked me up and down, surveying my body. I smiled (like I had been taught to do; smiles diffuse the situation) and kept walking, this time with a little more urgency.

When I was 12, another person in my family, older than me, assaulted me. They would whisper in my ear the things they wanted to do me. They would ask me to do things to them. I would say no. Sometimes they didn’t ask, they demanded. I had to say yes. When the rest of the family found out what was going on, I was beaten with a belt for being “fast” and he was thrown out of the house. We never talked about it again.

A friend of my grandfather, when I was 14, would stare at me, a drink always in his hand. I was afraid of what could happen, so, for the first time in my life, I decided to tell my grandmother how uneasy I was feeling. She told me to tell my grandfather.

When I told my grandfather about his friend (who was 40 years older than me), he looked me in my eyes and said, “Don’t pay him any mind. He ain’t gon’ do nothing to you.” That man continued to stare at my body with a look I have come to fear. I was relieved the day he died of cancer.

When I was 17, I was raped. In my own bed, in my own home. I went to school the next day. A year later, I joined my rapist at Western Washington University. He graduated that spring.

When I was 20 years old, I awoke to a man that I had invited into my home, raping me. I didn’t know what to say. I froze and, like that little girl with her underwear down, I lay in my bed motionless, silent, and afraid.

I am 21 years old now and I am still learning to love my battered body. I can finally say “me too.” It doesn’t erase the trauma, but it gives me back a fraction of the power that was taken from me too many times.

Me too. Me too. Me too.

For every 98 seconds that pass in each day, someone in this country is sexually assaulted. And it could happen to anyone. A woman, a child, a man. An inmate or a solider. You. Me.

It is difficult, draining, and overwhelming to try to grasp this fact, but we must do it.

To visualize the staggering violence that is being perpetrated and perpetuated all around us is to have your heart broken over and over. To acknowledge that someone you know is an assaulter is to have your trust shattered. To comprehend the commonness of rape culture in our country is to realize you may contribute to it. To discern that one out of every six women and one out of every 33 men in this country have been the victims of an attempted or completed rape in their lifetimes is to understand you are not invincible from this violence — and that, above all, is terrifying.

But, we must do it.

In the United States, Facebook reported that 45 percent of users have had friends who posted “me too.”

In the United States, Facebook reported that 45 percent of users have had friends who posted “me too.”