“This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. ... Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. ... There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. ... We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. ... We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until "justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream."” - “I Have a Dream”, delivered 28 August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C.

Minister, activist, scholar, and civil rights icon Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is remembered fondly and universally respected by all those who learn of his groundbreaking efforts for advancing the rights and conditions of African Americans. Ask any American you know and they will claim to share his vision and ideology of racial equality: likely referring to (the improvised conclusion) of his legendary “I have a Dream” speech. His legacy in public discourse is that of a peaceful, respectable man whose core message was people would “...not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” As a historical icon, almost everyone claims to agree with his ideology and touts him as a champion of racial colorblindness; some (mostly White) people allege that this event ended racism as we know it. The legacy of his largely universal message in common contemporary discourse is viewed as highly palatable and White-friendly as well as Black-friendly. A closer look at his message and his tireless efforts for civil rights show something very different. Dr. King was not a moderate, well-liked, champion of respectability politics, but a radical figure demanding a fundamental reassessment of American and Christian values. Where this gets lost in translation likely lies within what people either fail to remember about him, or were never taught to begin with. Oft forgotten are his indictments of American imperialism abroad and White apathy toward the plight of Americans of color. Similarly forgotten are his calls for economic justice, with emphasis on a living wage for workers and the propagation of diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Rarely does it seem taught that two-thirds of Americans held an unfavorable view of King in 1966, or that the FBI sent him a letter in 1964 encouraging him to commit suicide. Little remembered are his words to NBC News in 1967, stating that his dream “has turned into a nightmare.” This paper will draw attention to many of his more overlooked speeches and writings in which he fought for an end to militarism and economic exploitation as well as racism. I will also show how he promoted a restructuring of race relations that was compassionately color conscious rather than passively colorblind. I will also examine the way he presents the equally radical teachings of Jesus Christ and the foundational American values as part of his message. He presents Christian promises of love, charity and redemption, along with American promises of equality, justice and democracy both as unfulfilled by a system that seeks to exploit people rather than care for them. Next, I will analyze how his message has been watered down and coopted by public education, contemporary media outlets and common discourse to maintain a racial status quo of assumed equality rather than addressing the remaining inequalities that he fought his whole life. The ways that colorblind ideology, downplaying of racism, and historical construction of discourse are critical in understanding this phenomena. I will draw attention to the way his words related to the prevailing inequalities of race and class to this day, including police brutality, response to peaceful demonstrations and exasperated economic disparity between Blacks and Whites. Considering how much of an icon Dr. King has become in struggles for civil rights as a whole, these are important factors to consider.

“Many White Americans of goodwill have never connected bigotry with economic exploitation. They have deplored prejudice, but tolerated or ignored economic injustice. But the Negro knows that these two evils have a malignant kinship. ... With the ending of physical slavery after the Civil War. new devices were found to “keep the Negro in his place.”... the straitjackets of race prejudice and discrimination do not wear only southern labels. The subtle, psychological technique of the North has approached in its ugliness and victimization of the Negro the outright terror and open brutality of the South. The result has been a demeanor that passed for patience in the eyes of the White man, but covered a powerful impatience in the heart of the Negro.” - “Why We Can't Wait” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1963 (pgs. 10-13)

Perhaps one of the most commonly forgotten tenets of his message is his fight for poor, working people and Americans of all races. Dr. King’s intricate understanding of racial inequality as interconnected with economic exploitation was essential. His 1967 speech The Three Evils of Society decries capitalism as “...built on the exploitation and suffering of Black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor – both Black and White, both here and abroad.” Throughout the civil rights movement, he worked hard to cultivate an alliance between civil rights movements and labor unions, which he saw as the twin pillars of urgently needed progressive change. It is telling that contemporary history rarely refers to his famous March on Washington by it’s full name: The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; of which he had a massive attendance in favor both of civil rights for Black people and worker’s rights for all people. I would argue that this strong emphasis on economic inequality stems from his upbringing as the son of a middle-class Baptist minister, born in the onset of the great depression. He saw first hand the damaging effects of poverty within his congregation, even if his own family was economically well-off compared to most Black people of the time. His own devotion to the gospel of the Black Baptist church gave him a strong affinity for helping those in need. Considering 15% (roughly 2,350 in total) of all Bible verses are about man’s relationship with wealth—more than on any other topic—this ideology is indeed consistent with scripture. As a Christian leader who believed in the potential of salvation for all, Dr. King did this not only to save poor people from poverty, but rich people from the greed in their hearts: “In the final analysis, the rich must not ignore the poor because both rich and poor are tied in a single garment of destiny. All life is interrelated, and all men are interdependent. The agony of the poor diminishes the rich, and the salvation of the poor enlarges the rich. We are inevitably our brother's' keeper because of the interrelated structure of reality.” (Martin Luther King's Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech, in Oslo, December 10, 1964) This demand for upward mobility of the working poor also ties in with Dr. King's invoking of American values of equality and opportunity for all, which were not truly available to the poor, much less the poor and Black. He referred to these promises of the Declaration of Independence at a 1968 speech for the “Local 1199” labor union in New York City: “If a man does not have a job or an income, at that moment you deprive him of life. You deprive him of liberty. And you deprive him of the pursuit of happiness...” At the height of the labor movement however, the Red Scare was a convenient tactic in suppressing radical rejection of capitalism by branding its opponents as dangerous and Anti-American Communists. This was used as an excuse for the FBI to spy on Dr. King and other civil rights leaders, as well as create rifts within labor unions (many of which already segregated by race). This contributed significantly to Dr. King’s image as a controversial figure and the popular mistrust of civil rights and labor movements. His association with communism, significant divide in public opinion regarding civil rights and the war in Vietnam contributed to his low approval rating at the time. Since a civil rights bill was pending in 1963, Dr. King could have limited his focus on the immediately attainable advancement of African Americans for a more pragmatic approach of a single issue. Instead, he shot for the stars and called for a radical demand for fundamental change of a system that hurt everyone. Had he not spoken out as much as he did against war and economic injustice, he might not have been assassinated giving his speech to poor sanitation workers in Memphis. Diminishing his legacy to civil rights alone, and ignoring his movement in Memphis in favor of his assassination, is to ignore a massive part of Dr. King’s ideology. The idolization of his (watered-down) message over time makes us easily forget what made Dr. King the controversial figure he was, and ironically enough, we see many of the same discursive tactics used to undermine Black civil rights movements today under the guise of colorblindness.

“First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the White moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the White moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of goodwill is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.” - “Letter From Birmingham Jail” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1967

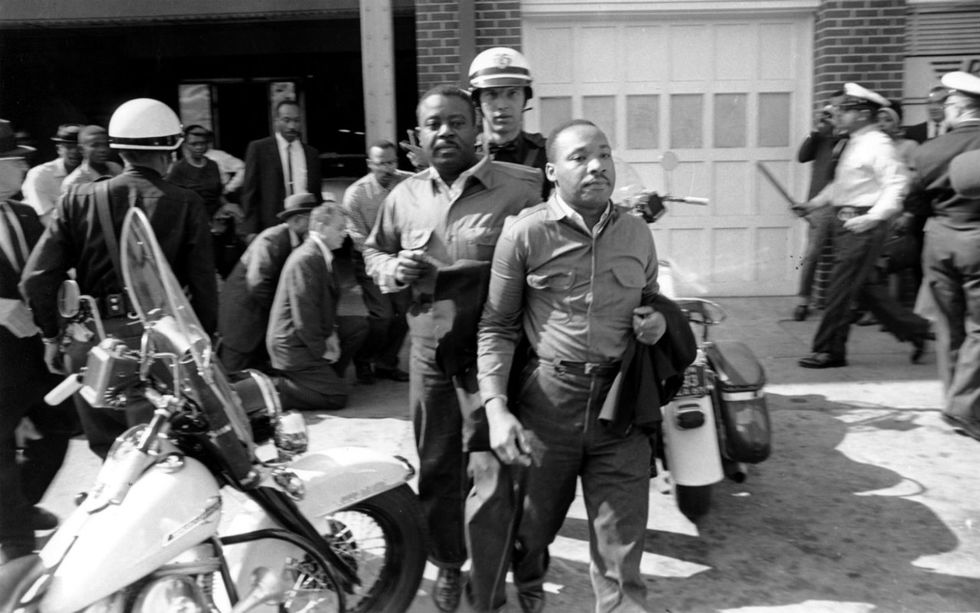

The public response to the Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s is strikingly similar to that of the civil rights movements in the 1960s. A poll by the American National Election Studies in 1964 showed that 66% of responders think the Civil Rights Movement “pushed too fast”, 56% believed most participants were violent, 56% said they “hurt their own cause". Responses to the Black Lives Matter movement use very similar mantras (on social media in particular) when voicing their opposition, even if that position is shrouded in concern with people of color’s well being. A pew research poll on Black Lives Matter in early 2016 show that only 43% of responders support the movement, 22% opposed it, and 30% either haven’t heard of it or don’t have a concrete opinion. The same poll shows that 38% of Whites and 8% of Blacks believe that “our country has made the changes needed to give Blacks equal rights with Whites”, 11% of Whites and 43% of Blacks believe that “our country will not make the changes needed to give Blacks equal rights with Whites” and roughly 41% of Blacks and Whites agree that “our country will eventually make the changes needed for Blacks to have equal rights with Whites”. Although these are differently worded polls with statistically significant difference of results, these results are still very telling. Almost everyone in this day and age claims to support the civil rights movement of the 60s along with Dr. King, but have developed very different perceptions on where the country stands in terms of racial equality. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva refers to this phenomena as racial ‘colorblindness’, in which the majority of (White) Americans in the post-civil rights era claim that they “don’t see any color, just people”. Colorblindness has been used as a convenient excuse to ignore issues of race & racism rather than effectively challenging it’s effects, as it operates in a more subtle manner. Based on what they do know about Dr. King, many (White) people will claim to be in line with his racial ideology by referring to select quotes of his. The quote most commonly referenced is the ‘content of their character’ quip of his I Have A Dream speech. Typically they will also claim that the same speech capped off the civil rights movement, which they may interpret as the ‘end of racism’ outside of isolated incidents of overt White supremacy. Particularly in the criticisms of today’s civil rights movements, the ideology of colorblindness fails to consider just how color-conscious Dr. King’s approach to racism was, as well as the ‘colorblind’ individual’s own color consciousness they choose to ignore. Conservatives and frustrated Whites will often decry Black Lives Matter and embrace Dr. King in the same sentence, implying that the respective movements were substantially different. This false dichotomy fails to consider Dr. King and other Civil Rights activists who participated in many similar demonstrations of peaceful civil disobedience, met with continued instances of police brutality, were jailed multiple times, demanded anti-racist legal action and expressed frustration with White moderates. In Dr. King’s letter from the Birmingham Jail in 1967, he discribed dangers of the White moderate... “...who is more devoted to “order” than to justice .... who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom...” as a greater threat than overt White supremacy. He offers similar criticism in the first chapter of his 1967 book, Where Do We Go From Here?: “The majority of White Americans consider themselves sincerely committed to justice for the Negro. They believe that American society is essentially hospitable to fair play and to steady growth toward a middle-class Utopia embodying racial harmony. But unfortunately this is a fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity. Overwhelmingly America is still struggling with irresolution and contradictions. It has been sincere and even ardent in welcoming some change. But too quickly apathy and disinterest rise to the surface when the next logical steps are to be taken. ... The recording of the law in itself is treated as the reality of the reform. ... This limited degree of concern is a reflection of an inner conflict which measures cautiously the impact of any change on the status quo. As the nation passes from opposing extremist behavior to the deeper and more pervasive elements of equality, White America reaffirms its bonds to the status quo. It had contemplated comfortably hugging the shoreline but now fears that the winds of change are blowing it out to sea.” Later on in the book he affirmed that “Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the White people of America believe they have so little to learn. ... Loose and easy language about equality, resonant resolutions about brotherhood fall pleasantly on the ear, but for the Negro there is a credibility gap he cannot overlook. He remembers that with each modest advance the White population promptly raises the argument that the Negro has come far enough. Each step forward accents an ever-present tendency to backlash.” These quotes eloquently oppose the tendency of White people to ignore the prevailing inequalities of race in favor of a comfortable status quo. I would argue it was this phenomena that lead to the increasing wealth inequalities between Black and White people, apathy towards biweekly murders of unarmed Black people by White police and becoming so ‘blind’ to their own racism they had the first Black president pass the torch to reality TV troll endorsed by the Klan. Indeed, this embrace of a comfortable yet imbalanced status quo is more dangerous in the long run than overt racism which can be easily called out. However characterization of Dr. King as a White-friendly champion of colorblindness didn’t come out of thin air: Indeed, he held tight to the virtue of loving one’s enemies (Loving Your Enemies, Christmas 1957), decried Black supremacy as equally dangerous as White supremacy (Social Justice and the Emerging New Age, 1963), held a dream of interracial harmony (I Have A Dream, 1963) and consistently held true to the principle of nonviolence. ‘Nonviolence’ has also been used among colorblind racists to deligitimize more recent activism for racial equality. Often times they interpret his commitment to nonviolence as a mandate for Black people to be nice to them, not to make them uncomfortable in thinking about race. Other times they insist that demonstrations by Black Lives Matter are violent and Dr. King would never do such a thing. This fails to consider that the overwhelming majority of Black Lives Matter protesters have used nonviolent demonstrations compared to very few isolated incidents of violence and/or property damage. A likely explanation of this is the cultural racism Bonilla-Silva points out as a component of colorblindness: that Black people are violent not because of their race, but the (Black) culture that cultivated their behavior. These same audiences might assume that any demonstration that is loud, watched by militarized police and gets in the way of traffic as violent simply because their media outlet of choice implied that it was. Are they too colorblind to consider the regular executions of unarmed Black people at the hands of police to be violence as well?

“Many people fear nothing more terribly than to take a position which stands out sharply and clearly from the prevailing opinion. The tendency of most is to adopt a view that is so ambiguous that it will include everything, and so popular that it will include everybody. Not a few men, who cherish lofty and noble ideas, hide them under a bushel for fear of being called different.” - The Words of Martin Luther King, Jr. by Coretta Scott King, Second Edition (2011), (pg. 24)

There are other factors at play in branding Dr. King as ‘colorblind’, utilizing the politics of history and (re)construction of contemporary discourse. Over the years different actors within the U.S. government have attached this term to Dr. King, at first in defense of his anti-racist vision, later in manipulation of it. In 1896, Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan—the only judge to vote against ‘separate-but-equal’ laws of Plessy v. Ferguson—insisted that "Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. “ Since its overturning with Brown v. Board of Education, colorblindness became a common theme promoted among segments of the civil rights movement. Come 1983, Congress would force Ronald Reagan to begrudgingly sign Martin Luther King Jr. Day in as a national holiday. Reagan worried he may be honoring a communist sympathiser, but seized the opportunity in his official 1986 proclamation of the holiday to frame the narrative of his movement. In this proclamation, he heralds Dr. King as a hero of racial justice, but makes no reference to his essential message of ending imperialism and economic inequality. This mostly symbolic gesture draws attention to the cruel irony of his racist comments and voting record: vetoing the Civil Rights Restoration Act, opposing the Voting Rights Act, nominating Jeff Sessions as a District Court judge, painting Black women as “welfare queens” and starting the "War on Drugs", later admitted to be racially motivated by others behind it. Vincent Harding, one of Dr. King’s close allies and ghostwriters called out this strange inconsistency in his book Martin Luther King, the Inconvenient Hero: “It was a strange embrace, especially coming from a man whose administration seemed determined to retreat to an imaginary America of the past, a man who had opposed all of the legislation for which King had fought and died and who was just then exulting in the invasion of Grenada—an act King would surely have passionately condemned.” (2) On the same year Reagan proclaimed Dr. King’s holiday, he selectively attributed King’s ‘content of their character’ quote as a mantra of colorblindness in opposition to affirmative action. If he referred to different Dr. King quote in Why We Can’t Wait, he may have taken a completely different stance on affirmative action: “The Negro today is not struggling for some abstract, vague rights, but for concrete and prompt improvement in his way of life. ... In asking for something special, the Negro is not seeking charity. He does not want to languish on welfare rolls any more than the next man. He does not want to be given a job he cannot handle. Neither, however, does he want to be told that there is no place where he can be trained to handle it. So with equal opportunity must come the practical, realistic aid which will equip him to seize it. Giving a pair of shoes to a man who has not learned to walk is a cruel jest.” With all this on top of his policies that have significantly hurt the lower class, it’s baffling Ronald Reagan has considered himself an ally of King’s for nearly half of his presidency. I would argue that this phenomena shows a trend that almost anyone can claim to be in agreement with Dr. King on paper, but actively go against everything he fought for in practice. Thus, the cruel iconography of history has all but watered down Dr. King’s radical, eloquent and urgent message in favor of flowery figurehead of non-performative and uncritical anti-racism.

Is the dream of Dr. King dead already? Have we as Americans grown too apathetic to oppose the giant evil triplets of racism, militarism and economic exploitation? Is there still a way to ‘the mountaintop’? On a July 2013 interview with Democracy Now!, Dr. Cornel West mourns that “Brother Martin would not be invited to the very march in his name, because he would talk about drones. He’d talk about Wall Street criminality. He would talk about working class being pushed to the margins as profits went up for corporate executives in their compensation. He would talk about the legacies of White supremacy.” Though this thorough watering down of Dr. King’s message is something I find personally depressing, I do find solace in the fact that a Black, Southern, self-identified Socialist with a radical, progressive and urgently transformative message can be considered universally agreeable later on, even if it’s under false pretenses. By limiting the legacy of this legendary and influential hero to one speech -- sometimes only a phrase or two in one speech -- institutions such as K-12 education, public discourse and contemporary media are free to fill in the blanks with whatever feels comfortable. Whether those blanks are filled solely with civil rights, involvement, colorblindness, or even the opposite of what he fought for; such is the the power that historical framing of discourse can have on the perception of an individual. Ironically enough, “I Have A Dream” itself discusses many important aspects of his ideology as Vincent Harding points out: “The speech is profoundly and willfully misunderstood, people take the parts that require the least inquiry, the least change, the least work.” The dream of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is as important then as it is now, not because it easy, but calls for hard and consistent work to demand the impossible promised land of more genuine racial equality. I may not get there with you, but I dream that one day Dr. King’s true vision of equality, sustainability and peace becomes something for which we would all tirelessly march.

Bibliography:

Franklin, Andrew K. "King in 1967: My dream has ‘turned into a nightmare’." NBCNews.com. August 27, 2013. Accessed March 8, 2017. http://www.nbcnews.com/news/other/king-1967-my-dream-has-turned-nightmare-f8C11013179.

Goodman, Amy, and Juan Gonzales. "Cornel West: Obama's Response to Trayvon Martin Case Belies Failure to Challenge "New Jim Crow"." Democracy Now! July 22, 2013. Accessed March 8, 2017. https://www.democracynow.org/2013/7/22/cornel_west_obamas_response_to_trayvon.

Harding, Vincent. Martin Luther King the Inconvenient Hero. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2008.

"Letter from Birmingham Jail." Martin Luther King, Jr. to Christian Ministers. April 16, 1963. Birmingham City Jail, Birmingham, Alabama.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "Loving Your Enemies." Speech, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery, AL, December 25, 1957.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "I have a Dream." Speech, The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC, August 28, 1963.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "Social Justice and the Emerging New Age." Speech, Herman W. Read Fieldhouse, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, December 18, 1963.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech." Speech, Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, Norway, December 10, 1964.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. and Coretta Scott King. The Words of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: Newmarket Press, 1967.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "The Three Evils of Society." Speech, National Conference on New Politics, August 31, 1967.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "Local 1199 Salute to Freedom." Speech, Hunter College, New York City, March 10, 1967.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. "I've Been to the Mountaintop." Speech, Memphis Sanitation Strike, Mason Temple, Memphis, TN, April 3, 1968.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. and James Melvin. Washington. A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. San Francisco: HarperOne, 1991.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Why We Can't Wait. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2010.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Coretta Scott King, and Vincent Harding. Where do we go from here: chaos or community? Boston: Beacon Press, 2010.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. and Michael K. Honey. All Labor Has Dignity. Beacon Press, 2012.

“On Views of Race and Inequality, Blacks and Whites Are Worlds Apart.” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (June 27, 2016) URL, Accessed March 8, 2017.

Political Behavior Program, the Survey Research Center of the Institute of Social Research, University of Michigan. AMERICAN NATIONAL ELECTION STUDIES, 1964 TIME SERIES STUDY, VAR 640104-640107. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer and distributor], 1999.

Ronald Turner, The Dangers of Misappropriation: Misusing Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Legacy to Prove the Colorblind Thesis, 2 Michigan Journal of Race and Law 101-130 (Fall 1996)