When the NFL announced that Coldplay, Bruno Mars and Beyoncé would come together for a single, cohesive performance at the Super Bowl 50 halftime show, I didn’t get it. Coldplay would be taking the stage with two artists who had held their own in the past, and it was clear that they would be upstaged. But I’ve been surprised in the past, and I hoped that would happen again this year.

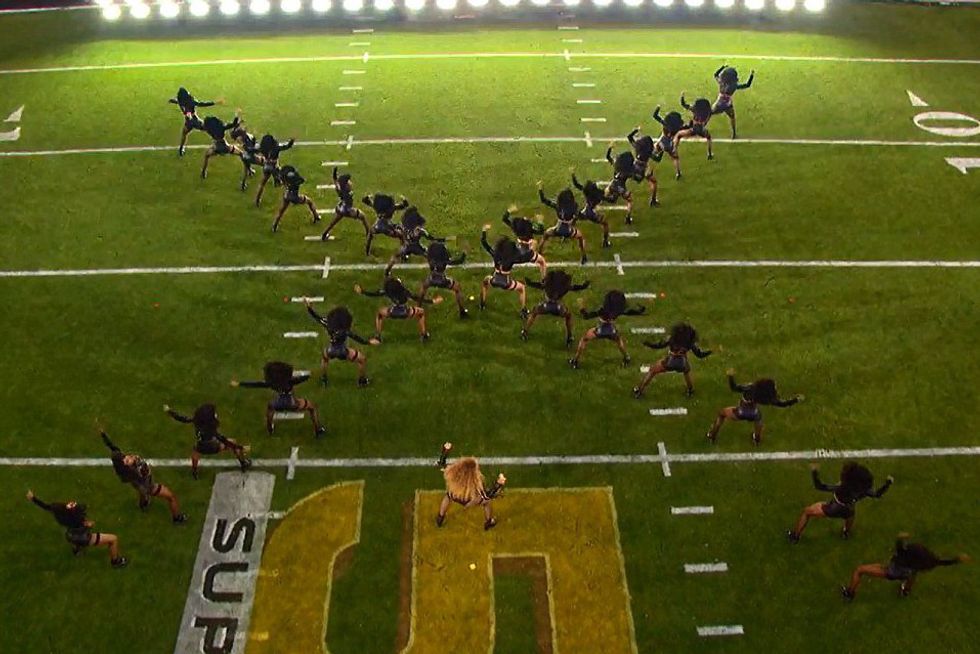

And yet, when the time came for them to actually take the field together, I still didn’t get it. It felt disjointed, like three separate performances vying for center stage, trying to make a statement, but—for the most part—it was unclear what exactly that statement was. For everyone except Beyoncé, of course. I didn’t quite understand (and I still don’t, to be honest) how exactly her brief “Formation” performance fit in with Bruno Mar’s “Uptown Funk” or Coldplay’s “Paradise” or “Viva la Vida,” but, without even having listened to the newly released song, it was obvious from her Black Panthers and Malcolm X references that she had one thing to say: Black lives, black culture and black history matter.

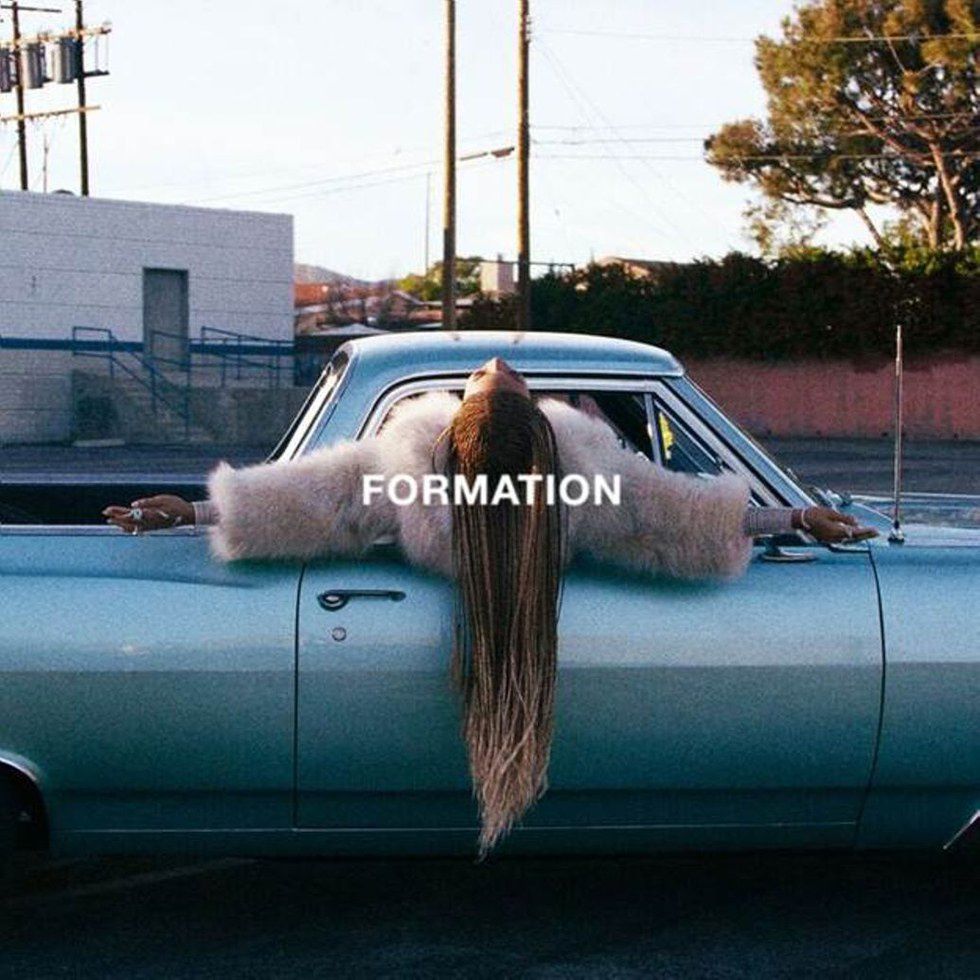

While her performance at the Super Bowl stirred up controversy, it was nothing compared to the lingering debate over the music video she released the day before. Beyonce dropped “Formation”—the song and the video, released exclusively on Tidal—a day before Super Bowl 50, and it was all anyone could talk about. As Suzanne Moore from The Guardian acknowledges, Beyonce looked “unapologetically black,” an indirect reference to sometimes appearing too white and not staking a claim in her own black pride. Beyonce very rarely talks about politics or makes her political views publicly known, and “Formation” is the first time in a while that we can actually hear what Beyonce has to say beyond her own personal politics (love, life, family, etc).

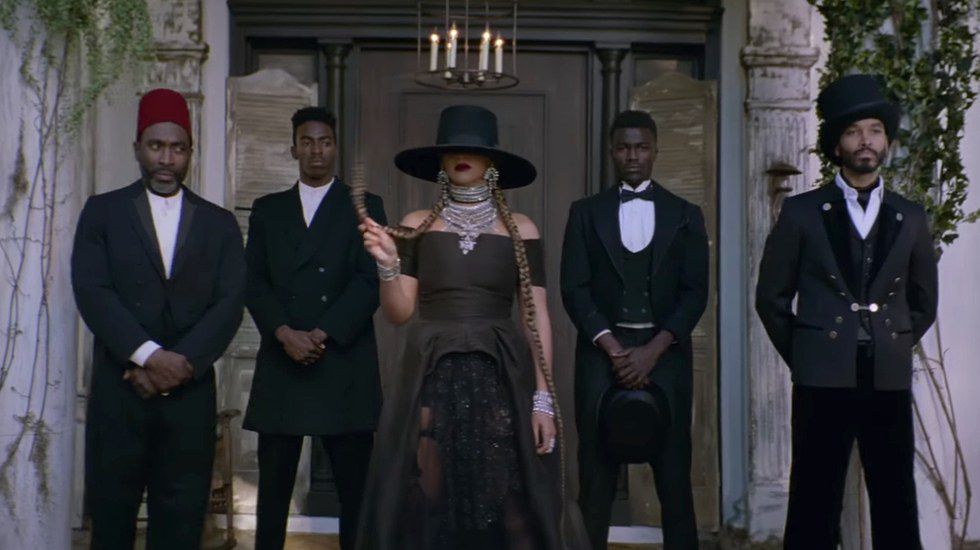

The setting of the “Formation” video references the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, a sort of homage to Beyonce’s southern roots, with a very clear, current message. It shows her straddling a New Orleans police car, and eventually she and the cruiser become submerged in water. It features Beyonce as a Southern matriarch. It pans the length of the once-beautiful, now-destroyed city and settles on the graffiti behind a group of huddled police officers : “Stop shooting us” is in bold, black letters.

“Formation” has caused a lot of controversy. It speaks to a time, place and general group of people who historically have always been at the bottom of our totem pole in history—something not many people want to acknowledge. We tend to think of racism as a thing of the past—but we are far from it. Beyonce gives us concrete examples of just how non-progressive we, as a society, are by comparing the Black Lives Matter movement with historical racism and slavery in the South. Beyonce is telling us that for every stride we think we are making in this modern civil rights movement, we aren’t. “Formation” paints us with a picture of post-Katrina New Orleans, with houses still in ruins and communities still at a disadvantage—a direct hit at the 2008 Bush administration’s unwillingness to help these disenfranchised, historically black communities. But “Formation” also gives us allusions to Bey’s personal beliefs and gives us striking visuals that are hard to forget, and even harder to talk about (houses submerged in water, a little boy with his hands up surrounded by white officers). Perhaps this is the reason why it seems no one can stop talking about “Formation,” because we like to think racism and discrimination is nothing but a page in our history books.

Bey’s been critiqued for being “too white” in the past, and “Formation” confronts that head on (I like my baby heir with baby hair and afro/I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils) and does it in a very confrontational way—something Beyonce isn’t typically known for. She’s speaking to her critics, her history and her future: My daddy Alabama, Mama Louisiana / you mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bama. She takes this word “bama”—as Jenna Wortham from The New York Times says, one of the most lethal insults you could be called growing up—and uses it as a defining figure for herself. She’s a black, Southern woman; she remembers her roots and her culture, and she unapologetically uses “Formation” to say she knows where she came from, but she also knows where she is now by acknowledging her wealth and her place in the industry (I might get your song played on the radio station…I just might be a black Bill Gates in the making). She’s set up “Formation” visually to recall her Creole South roots and the racial history there and compare it with how our media is treating the Black Lives Matter movement in the context of Katrina.

So, once again, “Formation” is categorized as controversial, but honestly…why? It’s all anyone could talk about in the days following Super Bowl 50, critiquing the way Beyonce chose to enter into this racially charged conversation. But that feeling of being off-put by the use of Black Panthers and Malcolm X references, striking Katrina visuals and catchy-but-relevant lyrics could be the first step for a lot of people in realizing the truth about race relations in America. Beyonce is one of many artists ushering in this new wave of the civil rights movement, and as a powerful black figure in American culture, this conversation makes America uncomfortable. But isn’t that more on us than it is on Bey? If her symbols of black power and police brutality in her video are making headlines more than the events themselves, then we’re not painting an honest picture of ourselves.

“Formation” isn’t controversial. The conversations and events being openly and honestly discussed are controversial. It’s that guilt factor that we, as a nation, tried to suppress for so many decades. Beyonce uses “Formation” as a reality check. If you’re uncomfortable watching or listening to it, think to yourself: why?